XF-85 GOBLIN: AMERICA’S PINT-SIZED FIGHTER FOR FLYING AIRCRAFT CARRIERS

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation’s XF-85 Goblin was to be a fighter unlike any other. It was tiny–so small it was often referred to as a “parasite” fighter–and instead of taking off from runways, it was intended to be deployed from the inside of flying aircraft carriers.

When the United States was plunged into World War II by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the nation was not the military powerhouse it is today. The Japanese and Germans were indeed aware of America’s potential strength, but that was really more a measure of the nation’s industrial infrastructure and population. In 1939, two years before the attack on Pearl Harbor, America had only 174,000 troops in the entirety of its military. Of course, within just six years, the United States would emerge as the most potent military power on the planet.

By 1946, America’s military had grown to over 16,000,000 troops, demonstrated the destructive power of its atomic weapons on the world’s stage not once, but twice, and was beginning test flights on a bomber with the largest wingspan in history. The combination of America’s nuclear weapons and this new bomber, the aptly named B-36 Peacemaker–with its 10,000-mile range–left America without equal in the days immediately following World War II.

But even then, America knew there would be challengers on the horizon. The Soviet Union, already positioning themselves for conflict with the West in the waning days of the second Great War, was hot on America’s atomic heels. The U.S. needed more than a bomber with global range, more than atomic bombs with seemingly limitless destructive capabilities… it needed a way to ensure that bomber could reach its targets to successfully deter a whole world’s worth of competition.

But with such incredible range, no fighter on the planet could escort the mighty B-36 all the way to Moscow and back. So, the team at McDonnell Aircraft came up with a new idea: Have the massive bomber carry its own support fighters.

Flying aircraft carriers and parasite fighters

If any aircraft could handle carrying its own backup, it was the B-36. Conceived before intercontinental ballistic missiles came into vogue, the Peacemaker was the largest piston-engined bomber ever to roll through an assembly line. It could carry an astonishing 86,000 pounds of ordnance, 16,000 more than the modern heavy payload titan B-52 Stratofortress, and could fly from American airstrips to Moscow and back without needing to refuel. The bomber was so massive that one of them was even converted to operate on nuclear power, hanging a 35,000-pound reactor from a hook in its middle bomb bay.

With that kind of payload capability, the B-36 could potentially carry a number of small aircraft internally or on external pylons and still have plenty of room left over for nuclear or conventional ordnance.

Related: NB-36 CRUSADER: AMERICA’S MASSIVE NUCLEAR-POWERED BOMBER

But despite the B-36’s massive size, it still wasn’t big enough to lug any of America’s existing air superiority fighters across the Atlantic. Most existing fighters were ruled out for technological reasons as well. Aircraft like the legendary P-51 Mustang, which had entered service just six years prior, were already outdated as compared to new jet-powered fighters that were already entering service. America’s first jet-powered fighter, the Bell P-59 Airacomet, first took to the skies in 1942, and the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star followed suit in 1944. If the B-36 was going to secure America’s future, its escort fighters couldn’t be stuck in World War II.

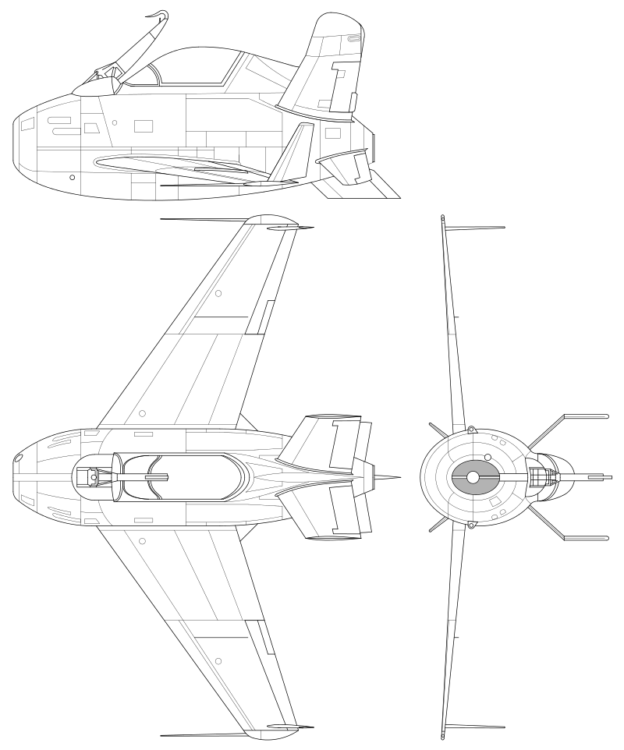

Initially, plans developed for the B-36 and similar bombers to carry their parasite fighters semi-exposed beneath their belly, allowing for a rapid drop into the fight when attacked. The Air Force soon scrapped that idea, however, citing concerns about increased drag, prompting McDonnel’s design team to return to the drawing board. When they came back, they had devised plans for a tiny, egg-shaped fighter with foldable, swept-back wings and notably, no landing gear.

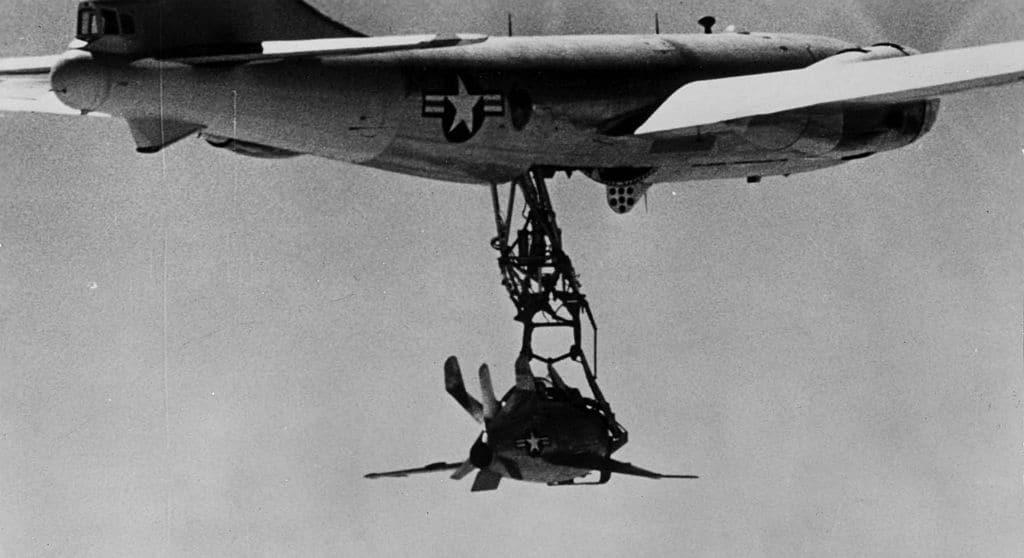

Theoretically, there’d be no need for landing gear, as this new parasite fighter would not only be deployed from the belly of the bomber, it would also be recovered by the same aircraft. A retractable hook on the nose of the plane would allow the pilot to close with a retractable trapeze beneath the bomber. The fighter would catch the trapeze with the hook and be pulled back into the aircraft. In order to support the concept further, Convair made plans to adjust its B-36 production to create a mix of aircraft intended to serve solely as bombers, and others that would carry a bevy of fighters to escort the bomber missions.

The concept wasn’t without precedent. Both the Royal Air Force and U.S. Navy had operated parasite fighters deployed from rigid airships to varying degrees of success and the Soviet Union had experimented with deploying fighters from their own TB-2 and TB-3 bombers. To some extent, the concept of flying aircraft carriers just seemed like the logical progression of airpower projection, and the assertion at the time was that making it work was just a matter of finding the right approach.

Goblins, Phantoms, and Banshees… Oh my

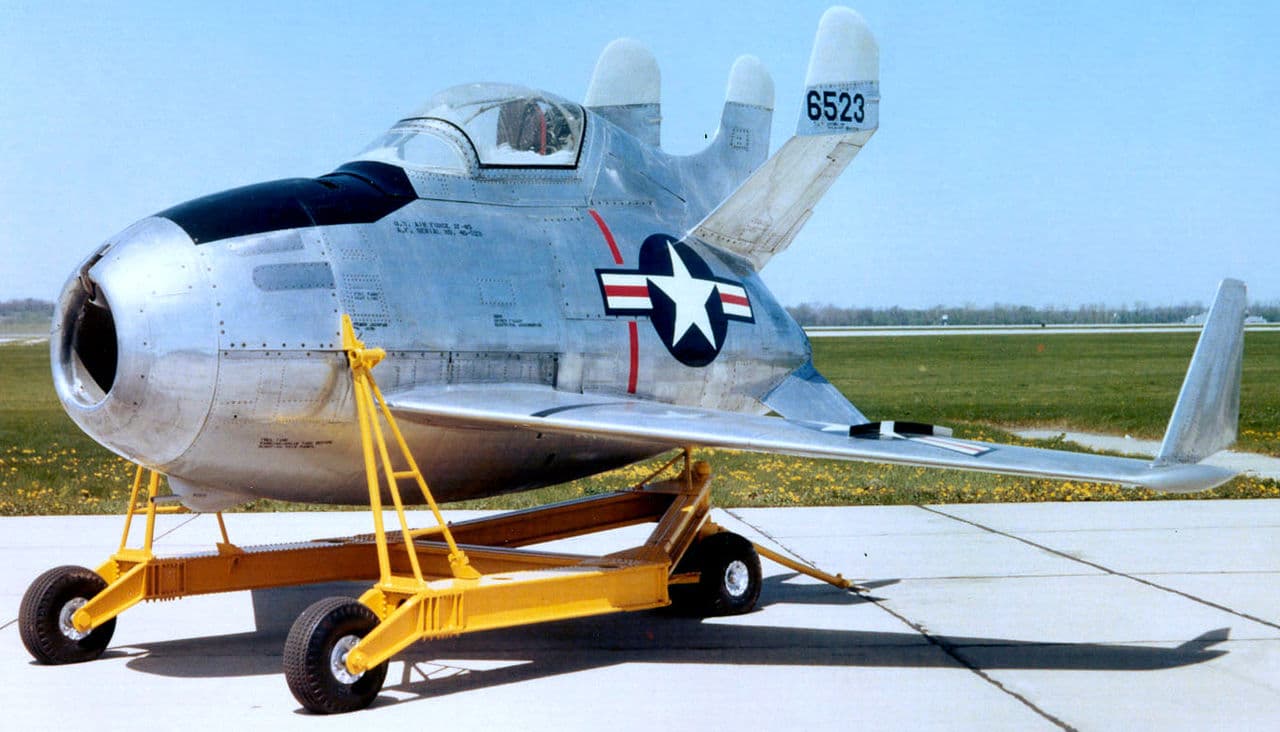

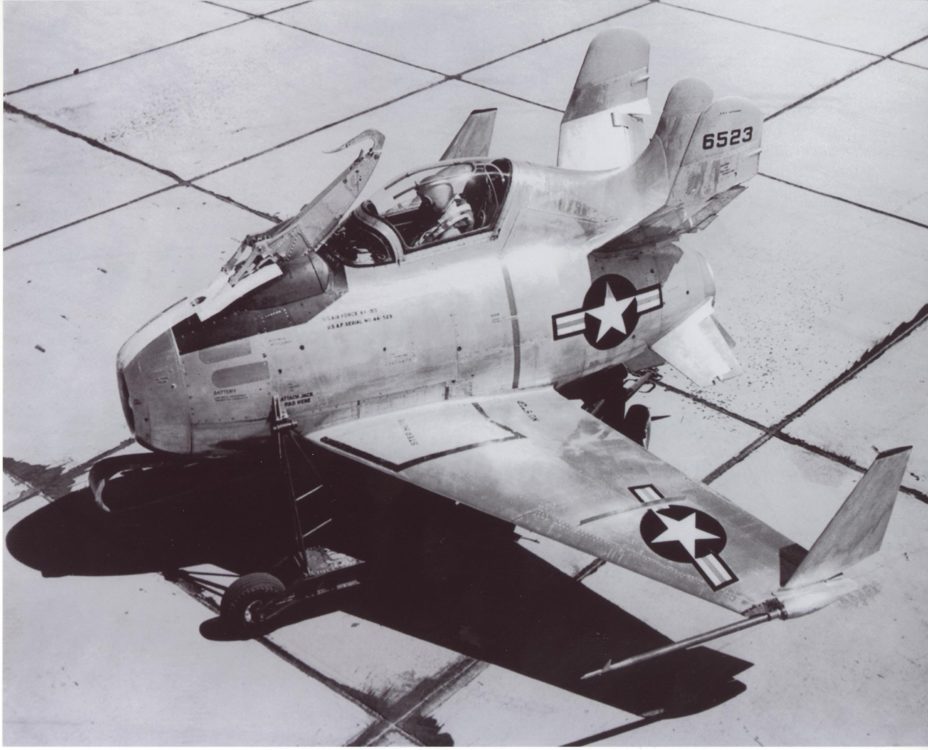

McDonnell Aircraft founder James McDonnell had a thing for the supernatural. In 1945, he unveiled the FH Phantom, the first jet-powered fighter ever to land on a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier. Then, in 1947, he gave the world the FSH Banshee, a fighter that would go on to earn prominence during the Korean War. In keeping with his fantasy-line of fighters, the tiny, bulbous parasite fighter McDonnell produced for the B-36 was dubbed the XF-85 Goblin.

The single-seat fighter was 14 feet 10 inches long with a 21-foot wingspan that could fold up to fit into a B-36’s bomb bay. The aircraft weighed in at under 4,000 pounds and was powered by a single Westinghouse XJ34-WE-22 turbojet engine that produced a respectable 3,000 pounds of thrust. The turbojet would push the XF-85 Goblin to a top speed of 650 miles per hour, with an operational ceiling of 48,000 feet. To hold its own in a fight, the parasite fighter was armed with four .50 caliber MR Browning machine guns. Despite its small size and lightweight construction, the Goblin still had a fully functional ejection seat in case the aircraft was hit by enemy fire.

The U.S. Army Air Forces (predecessor to the soon-to-come U.S. Air Force) agreed to fund the construction of two prototype XF-85s. There were no B-36’s available for testing, so plans were made to utilize an EB-29B Superfortress that had been extensively modified to support the parasite fighter. A “cutaway” bomb bay was added for the XF-85 Goblin to rest inside, along with a trapeze just like the one intended for the Peacemaker. A front airflow deflector was incorporated, along with a variety of cameras used to assess the success of the concept.

On July 23, 1948, the XF-85 Goblin rode into the sky for the first time, but wouldn’t be deployed from the bomber itself. It was the first of five captive-carry flights meant to show that the bomber really could operate with a baby-fighter in its bomb bay. Once that was clear, the Goblin was lowered into the airstream without engaging the engine–again, to give the bomber pilot an opportunity to see how his aircraft would react to the shifting aerodynamic situation.

With those successful flights behind them, McDonnell test pilot Edwin Foresman Schoch, who had ridden in the Goblin for the captive-carry tests, was ready to see what this new parasite fighter could do. For the team at McDonnell, it felt like they were on the precipice of a new era in military aviation. The time of flying aircraft carriers was at hand; all they had to do was make it work.

The XF-85 Goblin was easy to fly (and to crash land)

On August 23, 1948, Schoch and his XF-85 were released from their Superfortress mothership 20,000 feet above Muroc Field (now Edwards Air Force Base) in California. As the tiny parasite fighter was released, Schoch set to work, executing a 10-minute proving flight at speeds ranging from 180 to 250 miles per hour, demonstrating the aircraft’s basic maneuverability and testing its controls.

However, as he closed with his EB-29 mothership, the bomber’s draft created heavy turbulence that the tiny aircraft could only manage through intense pilot focus. The air cushion created by two other observation aircraft in close proximity made the situation even worse, and as Schoch approached the trapeze with his nose-hook, the situation seemed unsafe, and he backed away. After a moment, Schoch made another attempt, but was once again forced to back off.

Finally, Schoch pushed through the turbulance, but miscalculated his approach, colliding with the trapeze and damaging the Goblin’s canopy. Despite having his helmet and mask torn off in the collision, Schoch kept his bearing and got the tiny fighter under control, guiding it into a belly landing in a nearby dry lake bed. It was a disastrous first flight, and further testing was suspended for nearly two months.

During that time, changes were made to the XF-85 Goblin to make it more manageable for recapture, including boosting the trim power and adjusting the aircraft’s aerodynamic profile. Two more captive-carry flights followed before Schoch would make another attempt at successfully managing both a release and a capture from a flying mothership, which he accomplished on October 14 of that same year.

Further testing showed that the XF-85 Goblin itself was a pretty capable little airplane. It was considered very stable and user-friendly for the pilots onboard, and proved easy to recover from a spin. It seemed everything about the concept was working as it should, with the exception of the capture process.

On October 22, a bit more than a week after Schoch’s first entirely successful flight in the XF-85, the tiny fighter once again failed to hook on to the trapeze at the completion of its flight. After four attempts at managing the turbulence, Schoch finally managed to get the hook to the trapeze… only to have it break off as he made contact. For the second time, Schoch was forced to belly land the prototype aircraft in a dry lake bed.

Shoch would go on to belly land the XF-85 Goblin two more times after failing to successfully hook back up to the trapeze. Once on March 18 of 1949 and again on April 9.

The Goblin becomes fictional once again

The test flights of the XF-85 Goblin seemed to prove that the aircraft wasn’t going to be able to manage the job of serving as escort fighters for the B-36, but McDonnell still believed in the flying aircraft carrier concept itself. Aware that the Air Force wouldn’t want a parasite fighter that had a bad habit of crash landing every time it was deployed, they took proactive steps to come up with a new plan, a new fighter, and a new method of recovering the jets.

Their new fighter would be faster, nearly capable of breaking the sound barrier, and would be deployed and recovered using a trapeze system on a telescoping rod that could extend down below the turbulence created by the mother ship.

But the Air Force wasn’t as convinced that a flying aircraft carrier of this sort could work. Even if McDonnell could work all the issues out of deploying and recovering these parasite fighters, it was clear that only the most capable pilots would ever be able to manage such a feat, and even then, there was a high risk of failure.

But the real nail in the XF-85 Goblin’s coffin, as well as the entire concept of a flying aircraft carrier, was the broad adoption of in-flight refueling. While the concept had already been around for decades, it was only then becoming commonplace. While it did require some technical flying, the pilot requirements for in-flight refueling were still significantly lower than snagging the trapeze of a B-36 mother ship. The adoption of the Boeing KB-29P and its aerial refueling system in 1949 effectively spelled the end of flying aircraft carriers and their parasite fighters.

In all, only two XF-85 Goblins ever reached the skies a total of just seven times. Of those seven flights, the parasite fighter only made a successful capture with the hook and trapeze in three of them. The program was officially canceled on October 24, 1949.

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Military History

The AGM-181 LRSO missile will modernize America’s nuclear triad

Navy will soon announce the contract award for its F/A-XX 6th-generation jet, according to reports

America’s new air-to-air missile is a drone’s worst nightmare

What we can deduce about the Boeing F-47 and its capabilities so far

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page