Why stealth helicopters are so hard to design

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

In early May 2011, a CIA-led operation conducted by members of the Navy’s elite SEAL Team 6, also known as DEVGRU, took out the most infamous terrorist leader of the modern era, Osama Bin Laden. The mission, known internally as Operation Neptune Spear, was successful, though not everything went according to plan.

The plan called for the use of two highly classified and heavily modified UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters built specifically for clandestine operations. One of these stealth Black Hawks was meant to hover above Bin Laden’s walled compound for operators to fast rope in, while the other landed nearby to deploy troops, interpreters, and dog handlers to secure the perimeter.

But just as the mission started, things began to go wrong when one of the stealth helicopters crashed inside the compound.

Thanks to the pilot’s quick reaction, none of the operators or crewmembers onboard the helicopter were seriously injured, and the mission was ultimately successful. In order to prevent the stealth technology within the rotorcraft from falling into the wrong hands, the helicopter itself was destroyed prior to the special operations team’s departure.

Related: Why do officers have a higher success rate than enlisted men at becoming Navy SEALs?

But the exotic-looking tail section of this highly classified platform remained intact and left behind. It was clearly shown in pictures of the compound shared by media outlets around the world the following day.

Initially, the media didn’t seem to realize what they’d just shown the world… or perhaps the story of Bin Laden’s death simply warranted too much attention to address the uniquely angular and alien-looking tail rotor shown in the photographs. But it wasn’t long before journalists and aviation buffs around the world recognized how unusual the tail section really was, and came to a stark realization: Stealth helicopters are a reality. They’re in service. And none of us in the world at large, or even in the conventional side of the U.S. military, knew about it. At least, not until now.

Related: SEAL Team 6 parachute skills distinct among special ops

Stealth helicopters are extremely tough to design

Stealth is far more than a singular approach to radar evasion.

As detection and targeting capabilities continued to mature, so too did the technologies inherent to what we call “stealth.” Today, stealth designs take great pains to reduce not just radar detection, but also electromagnetic, infrared, acoustic, and even visual detection. It can be extremely difficult to incorporate these stealth design elements into fixed-wing aircraft, but one might argue that it’s even tougher when it comes to adding stealth to helicopters.

As retired U.S. Air Force helicopter pilot and former Air Force Weapons School instructor Mike McKinney put it, helicopters pose a number of unique challenges to the stealth enterprise because “they routinely operate within the heart of the threat envelope and their physical configuration does not allow for the use of many masking techniques.”

In other words, it isn’t enough to build modern stealth helicopters that can delay radar detection: rather, they also need to minimize the heat produced by the engines, the detectability of their radio transmissions, and importantly, in the case of low-flying rotorcraft, the noise produced by their propellers. Helicopters have large propellers, which are basically narrow wings being spun overhead. These tend to produce a significant radar and acoustic signature, while the helicopters’ powerful engines pump out a ton of heat, all in a platform that’s slower and less agile than modern fixed-wing aircraft.

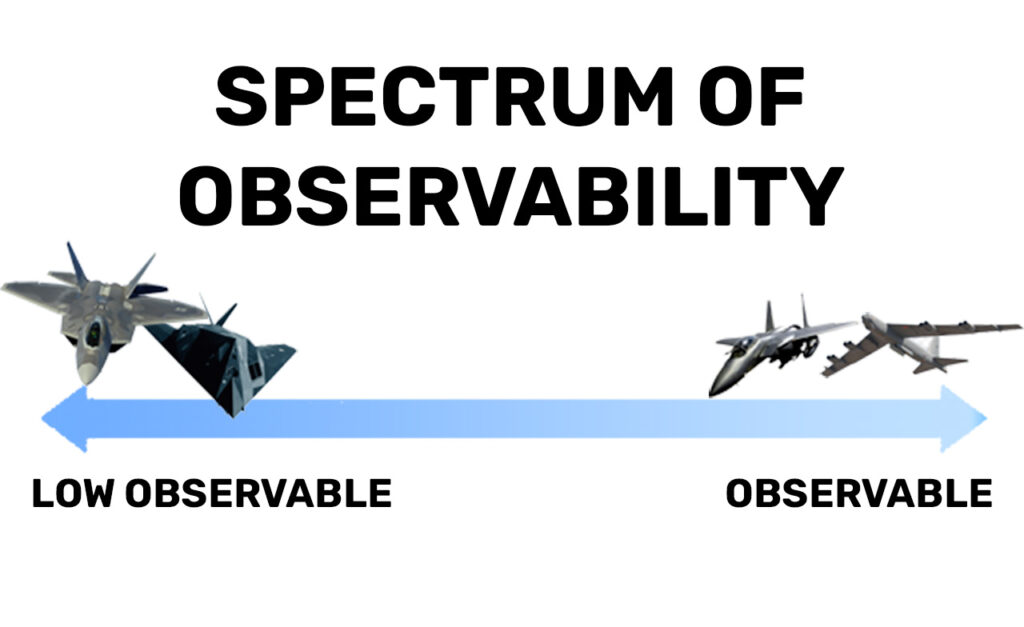

But it’s also important to understand that stealth isn’t a thing that a platform has or doesn’t have. It might be better to think of stealth as a segment within a spectrum of observability. On the broadly observable side, you have easy-to-spot platforms like the B-52 Stratofortress or the F-15 Eagle, and on the opposite “low observable” side, you have platforms like the F-117 Nighthawk and F-22 Raptor.

The degree of stealth required for a platform to be considered stealth in any given era is based not on clearly defined universal requirements, but rather on how a platform compares to the means of detection used in its day and to similar platforms of its class. Russia’s Sukhoi Su-57, for instance, may boast a worst-in-class stealth profile when it comes to its 5th-generation peers, but it is significantly stealthier than its 4th-generation predecessors. Its radar return may be thousands of times larger than an F-22, but it is dozens of times smaller than an F-15’s, pushing it far enough toward the low-observable side of the spectrum for many to consider it a stealth fighter.

The 90-degree angles inherent to helicopter design, as well as the ways in which these platforms operate, almost preclude them from ever achieving the sort of low observability that’s possible in bomber or fighter designs, but it is possible to design a helicopter that’s far less observable than its in-class peers and precursors, earning that coveted “stealth” designation, even if it will not be nearly as sneaky as its fixed-wing sisters-in-service.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Kerch Bridge is key in retaking Crimea, but can Ukraine take it out?

- Sandboxx’s Alex Hollings nominated for 5 Defence Media Awards

- The Soviet version of Operation Paperclip was way bigger (but less successful)

- What exactly is MARSOC, the Marines’ elite special operations component?

- The SOCP Fixed Blade’s great features and design make it a winner

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower

A Green Beret remembers his favorite foreign weapons

America’s new air-to-air missile is a drone’s worst nightmare

US appears to be staging stealth bombers for possible strikes against Iran

The Air Force is now adding AI pilots to combat-coded F-16s

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page