Few aircraft in history are as controversial as Lockheed Martin’s F-35 Lightning II. This aircraft, projected to cost the United States more than $2 trillion over its six-plus decades of service, saw repeated cost overruns, production delays, and technical setbacks over the 17 years since it first took to the sky, and today, you don’t have to go far to find someone calling this seemingly troubled fighter a failure.

However, the F-35 is also the most technologically advanced and broadly capable fighter in the sky today thanks to an immense amount of onboard computing power, sensor-fusing avionics, and a supremely low-observable design. This seemingly contradictory juxtaposition of real program issues and real platform capability has created a growing gap between perceptions of this aircraft and the actual value it offers to militaries.

The F-35 program has been the rightful recipient of lots of criticism over the years, but many outside the know often wrongly assume because of the F-35 program’s budgetary woes the aircraft itself doesn’t perform as advertised.

One could argue that few aircraft in history have ever suffered the sort of reputational sabotage in both news and social media that the F-35 has. This negative reputation is largely due to three things: the sensational headlining practices born out of our modern attention-based media business model; recency bias; and a lack of comparative transparency in foreign stealth fighter programs to form a basis for comparison.

The financial incentive to push bad news

In the world of defense media, some topics are all but guaranteed to drive a ton of traffic, and one of those is an article about something going wrong with the F-35 program.

This negativity bias isn’t unique to the F-35. When I took my first college journalism courses 20 years ago, one of the first things they taught us was the saying, “If it bleeds, it leads” an axiom sometimes attributed to William Randolph Hearst, about how headlines emphasizing death, destruction, or woe will always sell more papers.

In 2023 a group of researchers from universities around the globe came together to analyze 105,000 news stories that resulted in 370 million impressions and 5.7 million clicks only to confirm that, indeed, “negative words in news headlines increased consumption rates (and positive words decreased consumption rates).”

According to their findings, each additional negative word added to a headline resulted in a 2.3 percent increase in click-through rates, which is the ratio of overall people who see a headline versus the number who actually click on it.

A click-through rate of two percent is generally considered to be pretty good on search engines like Google. This means the addition of just one negative word to your headline could have a massive impact on the ad impressions you’re able to deliver, or in other words, the amount of money you can wring out of each article you publish.

So, there is a clear financial incentive for both news outlets and content creators to frame every F-35 story in the worst possible light.

The F-35’s recency bias problem

Recency bias, sometimes known as “availability bias” or the “recency effect,” is a cognitive bias that speaks to our inherently human habit of placing a greater emphasis on things we’ve been exposed to more recently, especially in cluttered informational environments like today’s complex web of news and social media.

You’ll often see people claiming that the F-35 crashes often, for instance, despite having one of the best safety records of any fighter in the modern era. In fact, the F-35 averages just 1.6 crashes for every 100,000 hours these jets spend in the sky – less than half of the F-16’s lifetime average of 3.55 crashes per 100,000 flight hours. Yet, headlines about F-35 crashes drive lots of traffic, and today, most people don’t recall the F-16’s troubled early years between 1975 and 1993, when the legendary Viper suffered more than double the branch average for aircraft losses. In fact, between fiscal years 1988 and 1994, an average of 17 F-16 airframes were lost per year, for an average of 4.21 airframes lost per 100,000 flight hours.

This comparison is meant to highlight how far-off perceptions of fighter programs can be as a result of media hyperbole and recency bias. The F-16 is an objectively successful program, with over 2,100 fighters still in active service all around the world (more than any other fighter): the F-35 is not only objectively safer, it’s also already among the most widely operated fighters in the world as well, with more than 1,000 airframes out there flying.

This recency bias also applies to readiness rates which are the subject of lots of F-35-related headlines. It has been widely reported that only around half of America’s F-35s are considered ready for a fight at any given time; a figure that is usually reported without any other context from the 96-page Government Accountability Office report that the claim originates from. That report, however, highlights precisely why F-35 readiness rates are so low and how exactly the DoD intends to fix them, which has little to do with the F-35 itself and is instead a question of completing the slow construction of repair depots meant to sustain these fighters for the coming sixty or so years. As that report put it:

“The analysis projected that if DOD achieved planned depot capacity, the air vehicle availability rates of the F-35B and F-35C would be close to 65 percent, while the air vehicle availability rate of the F-35A would be close to 75 percent.”

To give you the context that most coverage leaves out of this discussion, readiness rates of 65-75 percent would place the F-35 fleet on equal footing with aircraft like the supremely reliable A-10 Thunderbolt II (67 percent) and the F-16C (69 percent), while significantly outperforming air superiority fighters like the F-15C (33 percent) and F-22 (52 percent). Despite all the headlines you’ve almost certainly seen about F-35s not being ready to fight, you might be surprised to learn that in 2023 – the most recent year with publicly available figures – the Air Force’s F-35A fleet still had a higher mission-capable rate than a wide variety of other aircraft in service, ranging from fighters like the F-15C to bombers like the B-1B, and even cargo planes like the C-130H and C-5M.

While F-35 readiness rates have significant room for improvement, a good portion of the issue is simply the construction of maintenance infrastructure that already exists for older fighters like the F-15 and F-16. And despite being significantly more technologically complex and the inclusion of maintenance-heavy elements like radar absorbent coatings, the F-35 is projected to outpace older, easier-to-maintain jets in terms of fleet readiness once those facilities are complete.

How the Transparency Gap affects perceptions of the F-35

This combination of media sensationalism and recency bias also feeds directly into the third facet of the F-35’s reputational conundrum; something that I like to call the Transparency Gap between adversary nations operating 5th-generation fighters.

Despite the F-35 program being an international effort from its onset, the United States has led the program throughout, pulling from decades of research, development, and operational experience producing and flying low-observable aircraft. Today, the F-35 is one of just four operational 5th-generation fighters on the planet, sharing that unique distinction with America’s F-22 Raptor, China’s Chengdu J-20 Mighty Dragon, and Russia’s Sukhoi Su-57.

And while these fighters are often discussed on a one-to-one basis in online discourse, with debates about “who would win in a fight between one fighter and another,” that discussion itself, to some extent, is predicated on ignoring the F-35 program’s greatest success: its production numbers.

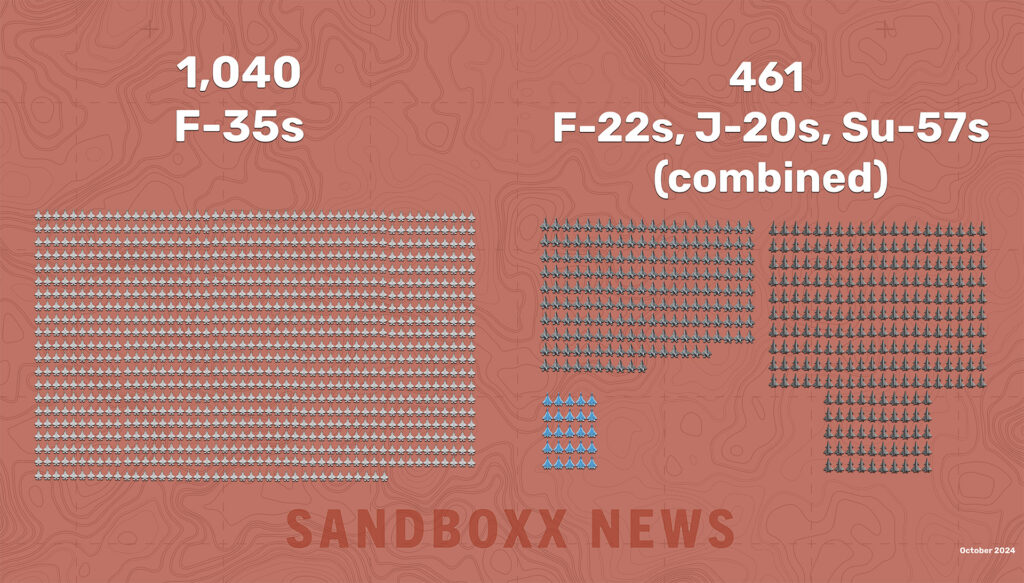

There have been more than 1,040 F-35s of all variants delivered to 10 different countries across 33 different air bases; and there’s now an American fleet of more than 630 F-35s. This represents not just the largest fleet of stealth fighters in the world, but the largest number of stealth aircraft ever produced.

America’s F-22 Raptor saw its production halted after just 186 airframes were delivered, with only around 150 carrying the requisite systems for combat.

To date, Russia has taken delivery on maybe 25 or so serial production Su-57s, including 2024’s dramatic reduction in production numbers due to ongoing sanctions. None of these aircraft, it’s worth noting, are powered by the platform’s intended 5th-generation turbofan engines, and instead, they all carry the older AL-41F turbofans also found in Russian 4th-generation jets like the Su-35M.

China’s Chengdu J-20, on the other hand, has seen significant production numbers in recent years, with some estimates placing the overall J-20 fleet strength at north of 250 airframes and a recent satellite analysis conducted by Janes suggesting that around 195 of these jets are actually operational. Like the Su-57, most of these J-20s also carry dated 4th generation engines, starting with the Russian-sourced AL-31, followed by multiple iterations of the Chinese equivalent WS-10, and the first images of a prototype J-20 flying with its intended 5th generation engine, the WS-15, only surfacing in September of this year.

That is to say that, even calling China’s J-20 and Russia’s Su-57 peers of 5th generation fighters like the F-35 and F-22 is debatable as both Russia’s and China’s efforts have yet to produce truly complete stealth aircraft. Instead, both airfames still carry dated, less efficient, less powerful, and easier-to-detect turbofan engines. But even barring that consideration, the United States alone operates more F-35s than all of the stealth fighters in Russian and Chinese service combined, and the sheer number of total F-35s out there outstrips even the combined total of all other stealth aircraft ever built by all countries, including the United States in history.

And because of the number of F-35 airframes in service and F-35 operators around the globe, that also means the F-35 has seen more combat operations than any other stealth fighter. The F-35 flew its first combat missions for Israel in May 2018, followed by the U.S. Marine Corps in September of the same year, the U.S. Air Force in April of 2019, and the UK a few months later in June. And while these missions were not all flown against integrated air defenses like the platform was designed to beat, these missions still reflect both the platform’s maturity and just as importantly, rapidly maturing doctrine built around leveraging these aircraft in combat.

The F-35’s combat experience has not been limited to air-to-ground operations, with a U.S. Air Force F-35A downing an Iranian drone over Syria in February 2023, and an Israeli F-35I successfully shooting down a Houthi cruise missile in November of the same year. Comparatively, the J-20 has yet to see any combat whatsoever and despite lots of Russian claims, the best evidence we have of the Su-57 ever seeing any action is a video that’s believed to show the fighter downing its own wayward drone wingman over Ukraine earlier this month.

But discussions comparing the F-35 to its 5th-generation peers often skip right past the platform’s massive numerical advantage and combat history, not to mention what are all but certain to be similarly lopsided figures for things like total flight hours (currently at more than 922,000), trained pilots (2,630+) and just as important, trained maintainers (more than 17,060).

The F-35 program is a stealth juggernaut in the sky, but legitimate comparisons between 5th-generation fighter programs are exceeding rare for one specific reason: America is very open about the F-35’s successes and failures while Russia and China carefully curate any public discussion regarding their advanced fighter programs.

If you want to argue that F-35 readiness rates are low, for instance, a reasonable counter-point might be, “okay, then how does F-35 readiness compare to other 5th generation fighters?” After all, it’s much more logical to compare F-35 readiness to other aircraft designed with similar stealth attributes, advanced sensor-fusing avionics, maintenance-heavy radar-absorbent skin, and fairly immature production and maintenance facilities. We can compare F-35 readiness to the F-22 Raptor, at 51 and 52 percent respectively in 2023, but we can’t compare either to China’s J-20 or Russia’s Su-57 because… neither nation discloses their readiness rates.

Adversary nations hide the flaws of their stealth fighter programs

We can assess pretty reliably that Russia has around two dozen serial production Su-57s, based on satellite imagery, its own public claims, and following the massive logistical tail of advanced fighter production. Yet, overhead imagery can’t tell us how many of those fighters are actually ready to fly, let alone fight. Likewise, China does not disclose how many J-20s it produces per year, how many are in flyable condition, how many can fight, or even overall numbers. We can assess via satellite imagery that today, China operates J-20s in at least 12 air brigades and may be building as many as 70 airframes per year.

Some production woes simply can’t be hidden, like these aircraft continuing to fly with dated, 4th-generation engines. Others, however, are much easier to hide. Take the F-35’s recent issues with its TR-3 upgrade which saw a slew of new hardware and systems integrated into new aircraft meant to support the upcoming and significant Block 4 upgrade. For a year, F-35 deliveries were halted, with dozens of these fighters piling up at Lockheed Martin facilities waiting for the kinks in the new systems to be worked out before deliveries commenced again in September of this year.

Because of American transparency, the F-35’s software issue has seen a great deal of media coverage and discussion, highlighting yet another setback in F-35 deliveries. However, if this same issue were present in China’s J-20 program, nobody in the West would know. We would simply see aircraft sitting on the runway at production facilities as numbers continue to accrue, but because software issues aren’t visible in satellite imagery, we would have no reason to conclude that those jets weren’t operational.

China is recognized by the Council on Foreign Relations as among the world’s “most restrictive media environments,” and is listed by the Committee to Protect Journalists as the world’s most prolific jailer of reporters. And while people will claim American media is controlled by deep state actors, China’s openly is.

In 2016, Chinese President Xi Xinping visited the nation’s three largest news organizations, where he very openly said the quiet part out loud.

“The media run by the party and the government are the propaganda fronts and must have the party as their family name,” Xi was recorded saying of the Chinese Communist Party’s relationship to the nation’s news media. “All the work by the party’s media must reflect the party’s will, safeguard the party’s authority, and safeguard the party’s unity. They must love the party, protect the party, and closely align themselves with the party leadership in thought.”

Related: China’s new Fujian carrier reignites the Great Aircraft Carrier debate

China’s use of carefully curated narratives that only portray Chinese efforts in a positive light ensures information about setbacks, failures, and other issues relating to high-profile programs like the J-20 simply never see the light of day unless word somehow slips past their censors.

Russian media censorship functions in a similar, though often more heavy-handed way. Not only are most large media outlets government-owned, but Russia also has a history of imprisoning and even killing journalists – and even everyday citizens – for stepping outside the bounds of approved narratives. In fact, in 2022, Russia even passed legislation allowing the state to sentence any individual to up to 15 years in prison for crimes as insignificant as calling the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine a “war.”

This carefully censored media landscape is then bolstered by widespread international disinformation campaigns meant to exacerbate negative perceptions of all things Western – especially military endeavors. These campaigns extend well beyond troll farms and bot commenters and now include things like hosting elaborate spoof websites meant to fool unexpecting users into thinking they’re reading articles from established news outlets, rather than Russian or Chinese-sourced propaganda.

These and similar campaigns are present across all social media platforms, including X, Facebook, and YouTube, and smaller communities in forums and elsewhere.

The average person isn’t aware of this transparency gap between American, and Chinese and Russian news coverage. As a result, they compare the frequent headlines they see about F-35 crashes, readiness rates, and cost overruns to sensational headlines about the threats posed by China’s rapidly expanding fleets of stealth fighters or Russia fielding advanced new engines for theirs.

The public is effectively stuck comparing the F-35 program’s whole iPhone photo reel, complete with unflattering selfies and blurry accidental shots of the bathroom floor, to China and Russia’s carefully curated Instagram profiles. As a result, Americans see headlines about the growing J-20 threat and wish their F-35 was progressing as smoothly.

Further, American media has a financial incentive to buy into these sensational fictions because reality rarely “breaks the internet” quite like a hyperbolic headline about an unsubstantiated claim about Russian or Chinese military capabilities.

The F-35 is an imperfect fighter, but imperfect is par for the course

The F-35 program has always been riddled with wasteful spending, shortsighted decisions, blatant errors in judgment, and unforeseen technological challenges. However, the scale and severity of these very real issues are often presented without the necessary context because that context is hard to come by and just doesn’t sell nearly as well.

And while the F-35 program continues to face challenges, this aircraft was designed to do things no operational fighter in history had ever done before: it brings technologies to bear that adversary fighter programs are still years away from putting into production even now, nearly two decades after the first F-35 took flight.

The F-35 is not a perfect jet. Every aircraft that’s ever made it into production has come with a long list of compromises, but the pervasive perception that the F-35 is a failure isn’t the result of its actual performance. It isn’t based on the reports of those who fly or maintain it. And when we do discuss the program’s real issues, we often forget entirely about finding a basis for comparison, in no small part because there has never been another stealth fighter program of such immense scale, success in foreign markets, or breadth of operational experience.

The F-35 Lightning II isn’t just the most technologically advanced stealth fighter ever to see service, it’s also the most successful stealth fighter ever to see production; the first stealth fighter ever to serve on an aircraft carrier; the first operational fighter ever to fly supersonic and then land vertically; the first fighter ever to be capable of flying its own electronic warfare support; the first stealth fighter to integrate an all-seeing helmet display with a distributed aperture system, and the list goes on and on.

The F-35’s combination of stealth and sensor fusion, more so than even the F-22 Raptor, represents a pivot point in combat aviation prizing technological prowess over brute force capability. That alone robs it of some of the cool factor you can feature in videos and articles about the twin-engine F-22, Su-57, and J-20. But while cool factor does drive clicks, it doesn’t necessarily win wars.

And winning wars is what the F-35 is all about.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- No, Russia’s futuristic Sotnik armor isn’t real

- B-2 strikes in Yemen were a 30,000-pound warning to Iran

- GM Defense hopes influencers will drive its new sci-fi-looking tactical pickup

- These exotic weapons were used by the Navy SEALs in Vietnam

- Wonder-weapons of World War 2: The German viper and the American goblin