What it’s like to visit Korea’s Demilitarized Zone

- By Hope Seck

Share This Article

The mine-studded and deadly dividing line between North and South Korea, a 2.5-mile wide strip of grassy land along the 38th parallel north, is one of the world’s most infamous spots. Known as the Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ, this near-uncrossable boundary was established with the Korean War Armistice in 1953 and remains in place seven decades later. As Koreans will remind you, the war never officially ended; it’s merely in a prolonged ceasefire.

The DMZ divides families and former neighbors; it also represents a separation between democratic South Korea, a growing world power and U.S. ally, and the mysterious and threatening nuclear dictatorship of Kim Jong-Un. Kim, the third in a dynasty of dictators, has continued to perpetrate the human rights abuses of his father and grandfather, and alarmed the world with missile tests.

In September 2022, Kim pushed the envelope further, changing North Korean law to clarify the cases in which the country would launch its nukes, and who would deploy them if something were to incapacitate the Supreme Leader. Amid all this, I got the chance to visit the DMZ and peer across the green at the strange, impoverished hermit nation capable of wreaking global havoc.

Our first checkpoint to the DMZ

My trip to the DMZ came courtesy of the Center for a New American Security’s Next-Generation National Security Fellows program, which arranged a learning visit to South Korea for members of the 2020, 2021, and 2022 cohorts. You do not, however, need to have special access or security clearance to visit the DMZ; you can book a tour from Seoul via a number of different agencies that will transport you by bus to the locations accessible to the public.

Expect to have your passport checked at multiple points by South Korean troops and pay attention to the dress code, which prohibits, among other things, flip-flops, shorts, skirts, athleticwear, and torn clothing.

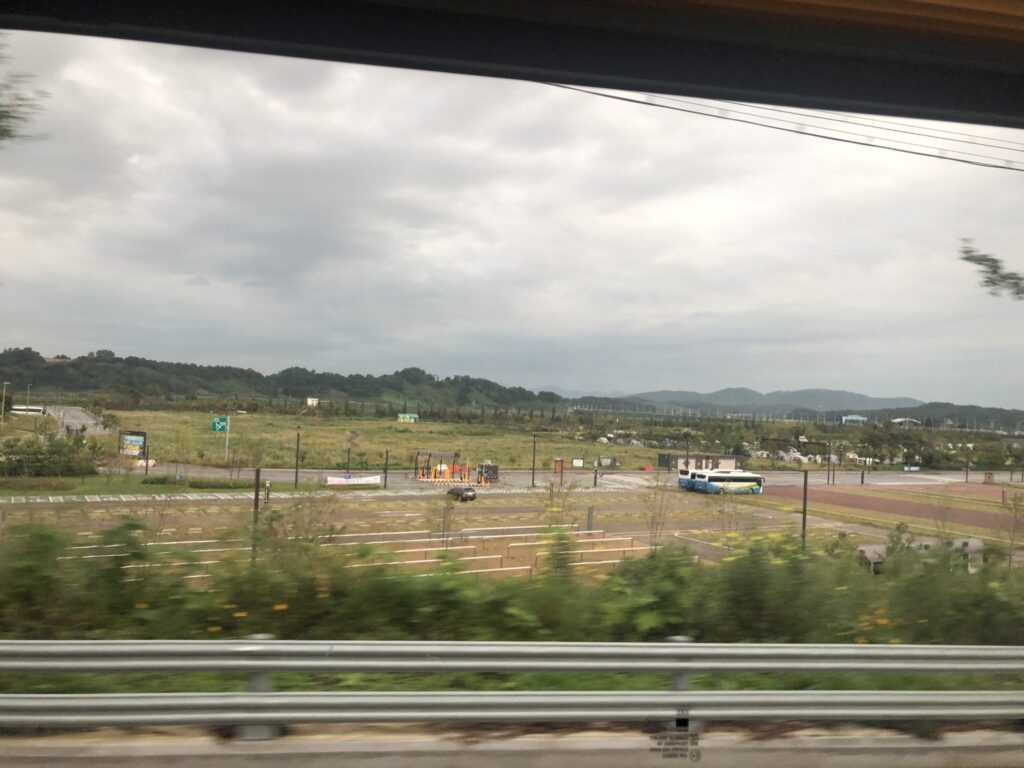

From Seoul, South Korea’s capital city in the northwest, we traveled about an hour north via bus, passing rice and ginseng fields and industrial sprawl. We hit a military checkpoint before our first stop: Imjingak Resort, a park about four miles from the DMZ that serves as its visitor center.

This location has the most touristy feel of the three spots we visited. It features a small fair-style amusement park with rides and even a concert venue, capitalizing on the novelty and weirdness of the place. There’s also a sky gondola that will take you above all the major sights.

But you’re never far from a reminder that this is a site built on decades of grief, tragedy, and conflict. At the entrance to the park is a memorial that plays a dirge-like song, 30 Years Lost, which scored a TV program in 1983 about separated families’ search for missing members.

Forty years after the show aired, the song is still playing and families remain divided. The memorial notes the melody is well-known in North Korea too.

Monuments of war

The focal point of Imjingak Park is the rusted carcass of a locomotive riddled with more than 1,020 bullet holes on a disused stretch of train track. The last train to cross into North Korea in 1950, on a supply run, it was stopped in Jangdan station, in what is now the DMZ.

According to operator Han Joon-ki, the train was actually destroyed by U.S. forces, who targeted it in a withering machine gun barrage to keep it from falling into North Korean hands. You won’t find that information at the memorial site, though – a reminder of the complexity of war and the politics of history. South Korea, which is careful to show its appreciation for its American allies during the war, doesn’t say who destroyed the train, only saying that the bullet holes and the bent wheels “show the cruel situation at the time.”

Steps away from the train is the Freedom Bridge, an homage to the Bridge of No Return, where thousands of prisoners were exchanged following the 1953 armistice.

Among those who at a later time walked across that bridge were the U.S. Navy crew of the USS Pueblo, an environmental research ship captured by North Koreans in 1968.

The bridge hasn’t been used for exchanges since then, although President Bill Clinton did walk over it – getting within feet of the North Korean border – in 1993. It’s the closest a U.S. president would get to crossing into North Korea until President Donald Trump walked over the line as a guest of Kim Jong-un in 2019.

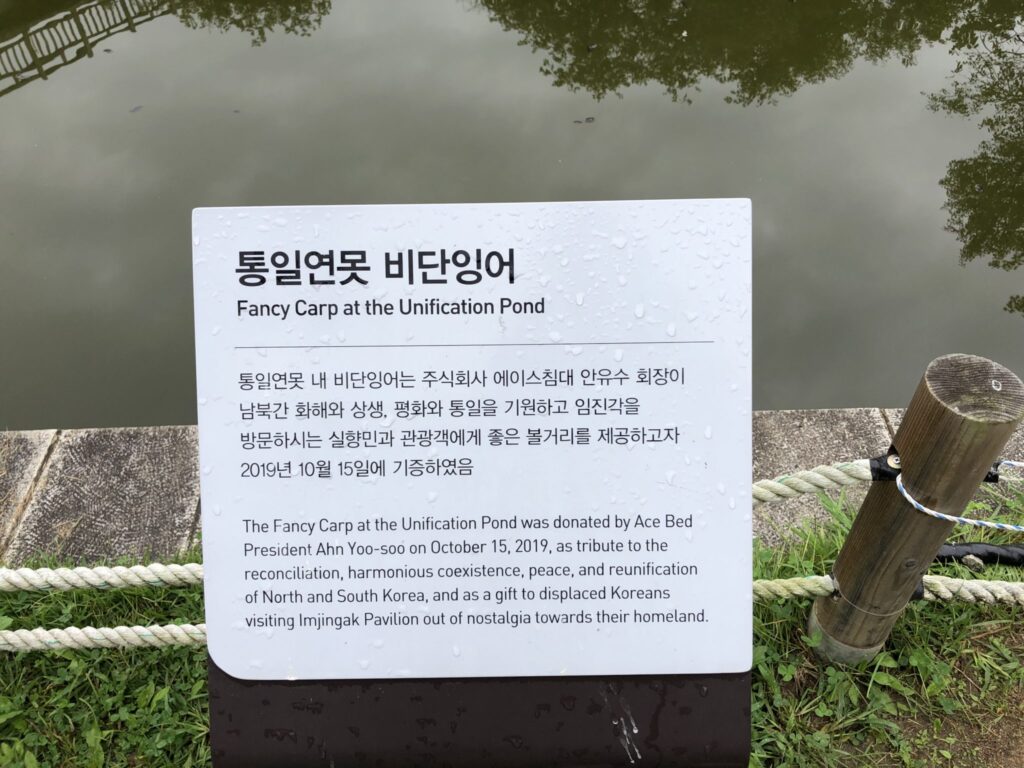

Below the bridge you’ll find orange carp swimming in a “Unification Pond.” At the DMZ, you’re constantly reminded of South Korea’s hopes that the two countries will reunite under a free government and live as one people again, despite the North’s continued acts of aggression and the 70 years that separate them.

There are plenty of monuments to atrocities – like the axe murder of two U.S. Army officers by North Korean soldiers in 1976 as the Americans attempted to cut down a poplar tree blocking their view of the border – but there are also lots of symbols of peace and hopes for a united future.

The Third Infiltration Tunnel

Our next stop on the DMZ tour was a tunnel dug under the border by North Koreans, the third of four discovered by the South during routine patrols and surveillance. Known to South Koreans as the “Third Tunnel of Aggression,” or “Third Infiltration Tunnel,” it’s incomplete at just a mile long, but still comes within 27 miles of Seoul. Rather than fill the tunnel in, the South Korean government opted to block it with three thick concrete barriers, then open the short section in front of those barriers to the public.

We weren’t allowed to take pictures inside the tunnel, and we had to wear yellow hard hats for the steep 358-meter descent.

A Korean soldier gave us a five-minute brief on the tunnel’s history and what we’d see. He explained that the tunnel was discovered in 1978 when soldiers found water shooting up from plastic pipes installed for the purpose of detection. While the North Koreans went as far as coating the walls with coal dust to make the tunnel look like a mining operation, he said, their story didn’t hold up: the tunnel’s walls are granite, with no natural coal to be found in the area. Moreover, he said, the tunnel was designed with a slight slope to the North to allow for water drainage and collection; and you can see dynamite holes, now highlighted with yellow paint, all directed from north to south.

As you descend into the infiltration tunnel, the surroundings quickly begin to feel more cave-like. Smooth poured concrete gives way to rocky granite and water appears on the floor and walls. By the time you hit the level floor of the tunnel, the rush of little streams is quite noisy and the ceilings quite a bit lower than the two-meter starting height. At the tunnel joint, the yellow-painted dynamite holes are highlighted further with the addition of two mannequins dressed like North Korean soldiers and holding shovels.

You’ll have to stay crouched for the remaining 255 meters until the third barrier. I kept forgetting to stay low and was glad, multiple times, that I was wearing a helmet. When you reach the third barrier, the end of the tunnel portion open to the public, you can peer through a small window to the second barrier. Between the two is a small untouched garden of grass and ferns – nature growing free where all else is kept out.

This was the closest we got to the border of North Korea on our tour. We were unable this time to visit the Joint Security Area, also known as Truce Village, where troops from both countries patrol the line and visitors on United Service Organization (USO) tours and with some companies, can walk into the very room where the Armistice was signed. Technically, the room crosses into North Korean territory.

You won’t find many U.S. troops patrolling the border in the JSA; in 2003, then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld ordered some 18,000 American service members pulled back, allowing them to be more mobile, operating from other outposts within the country. According to a 2008 U.S. Army article, about 650 troops patrolled the South Korean side of the DMZ at that point, 90 percent of them Korean and just 10 percent American.

The ‘propaganda village’

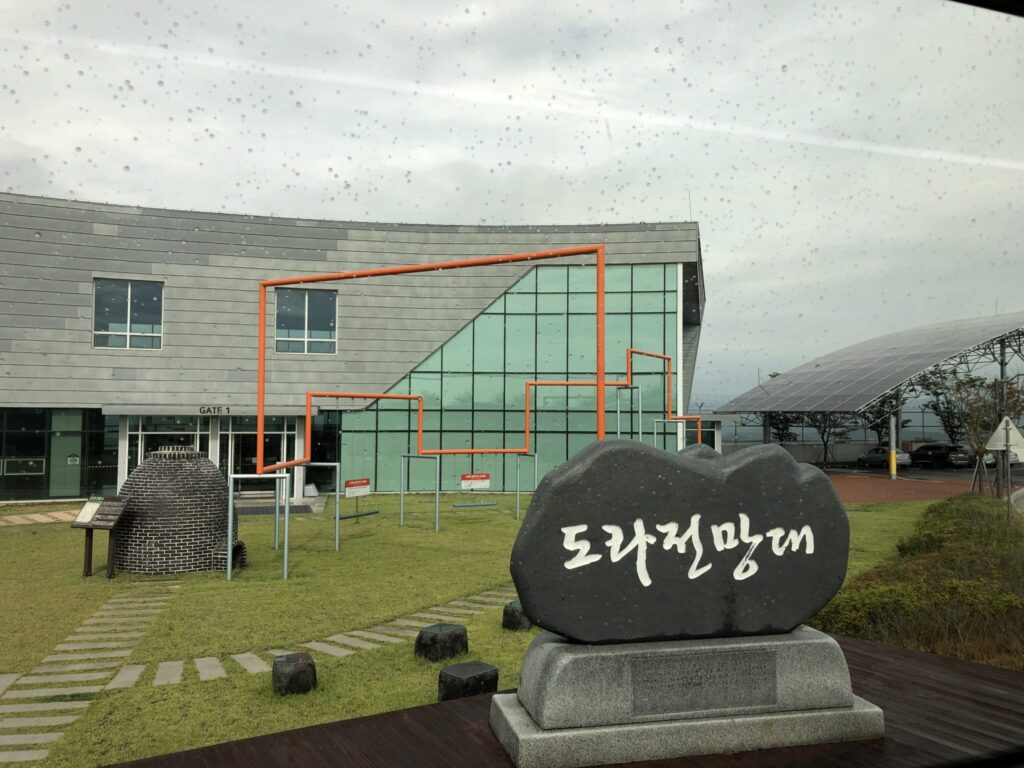

Our final stop was the Dora Observatory, named for the mountain it sits on, where visitors can use viewfinders and their naked eyes to peer into North Korea. Past lush trees stand two flags, one South Korean, and one – pointedly larger – North Korean. Beyond the North Korean flag the skyline of Kaesong, one of the country’s largest cities after Pyongyang, is visible.

At the base of the flagpole itself is a true North Korean oddity: Peace Village, or Kijong-dong, which it claims is a small farming community. South Korea, on the other hand, says it’s an uninhabited “propaganda village” where roleplayers occasionally come out and go through the motions of farming for the benefit of southern observers.

The village’s white buildings are mounted with loudspeakers that blast propaganda and anti-Western screeds at the border. Like so much in North Korea, appearances conceal a grim and repressed reality.

Back inside the observatory building, sign boards display photos from the 2019 summit between Trump, Kim, and then-South Korean President Moon Jae-in.

“Bold strides taken toward peace, prosperity and unification,” a caption reads over an image of Kim and Moon shaking hands.

The five years that have passed since, though, have brought little indication that unification is near. In May 2022, South Korea elected Yoon Suk-yeol, who took a hard-line stance against North Korea and aligned his nation more closely with American policy. President Joe Biden, meanwhile, did not show any signs of being willing to deal with Kim as a peer, as Trump did. And Kim’s continued aggression and missile testing have further slammed the door on hopes of meaningful reconciliation.

For the foreseeable future, things are likely to remain as they are now: an armed standoff on a border separating two countries, one free and one impoverished and oppressed, and quiet signs of hope that reunion and healing is just beyond view.

Feature Image: North Korea viewed from the observatory in the Demilitarized Zone. (Courtesy of author)

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in September 2022. It has been edited for republication.

Read more from Sandboxx News

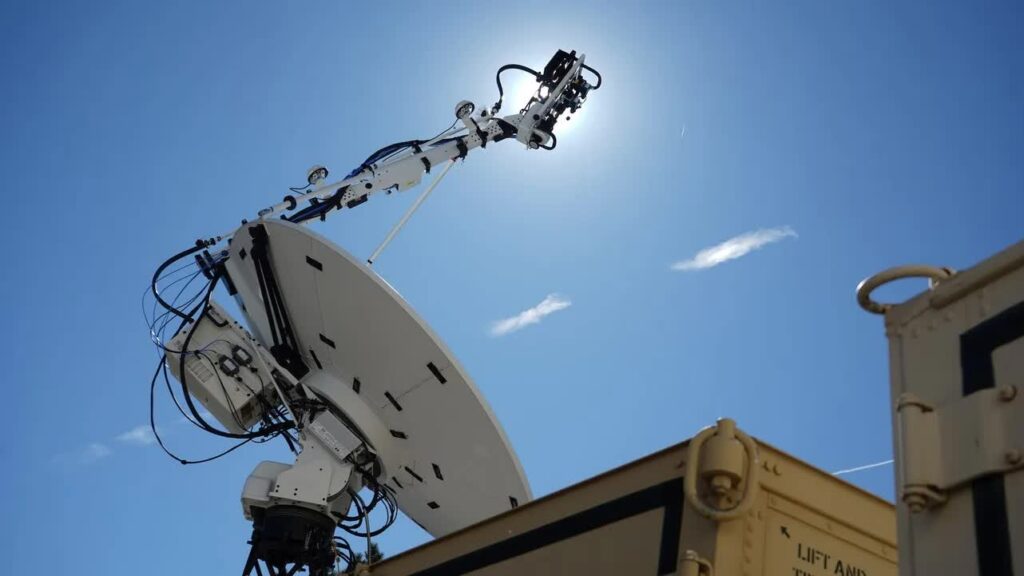

- Space Force to deploy new jammers to yell at enemy satellites

- Ukraine peace negotiations don’t look promising

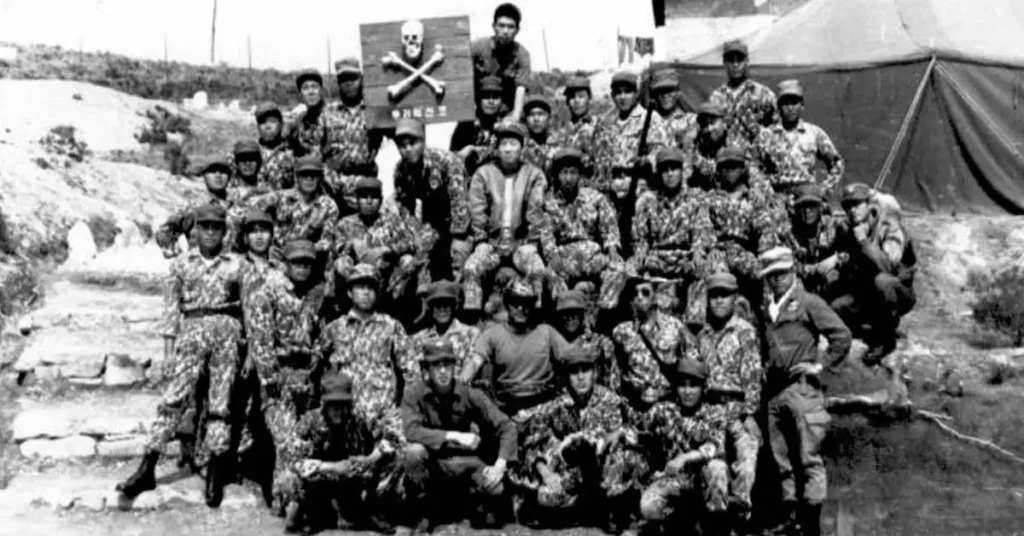

- Unit 684 – The South Korean suicide squad with the tragic history

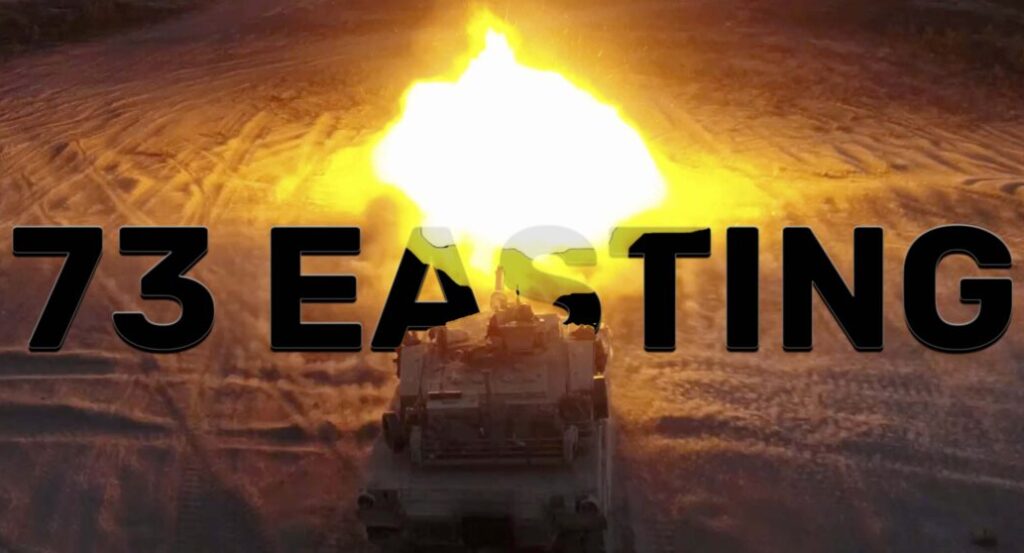

- How American Abrams tanks devastated Russian tanks in Iraq

- C-5 Super Galaxy: Anywhere in the world in 24 hours

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart -

A-10 ‘Warthog’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Hope Seck

Hope Hodge Seck is an award-winning investigative and enterprise reporter who has been covering military issues since 2009. She is the former managing editor for Military.com.

Related to: Military Affairs, Pop Culture

Space Force to deploy new jammers to yell at enemy satellites

Ukraine peace negotiations don’t look promising

Unit 684 – The South Korean suicide squad with the tragic history

How American Abrams tanks devastated Russian tanks in Iraq

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page