What exactly are hypersonic missiles and why do they matter?

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Over the past few years, Russia, China, and the United States have invested billions of dollars into the development of a new weapons technology commonly referred to as “hypersonics” or, in particular, hypersonic missiles. These new missiles promise to change quite a bit about how the United States goes to war, both as a result of employing new weapons and as a result of trying to defend against them–but in order to appreciate how things will change, first we’ve got to understand why.

What does “hypersonic” even mean?

Hypersonic missiles are missiles that are capable of maintaining speeds in excess of Mach 5, or around 3,800 miles per hour. At that speed, hypersonic weapons are carrying enough kinetic energy to destroy many targets without the need for an explosive warhead, and worse still, they are all but impossible to defend against using even the latest missile defense systems available in any nation’s military.

Today, a number of hypersonic platforms are under development for a variety of applications, but the most pressing uses of hypersonics among America’s competition come in the form of Russia’s nuclear-tipped Avanguard missiles and their Zircon cruise missiles, and China’s DF-ZF hypersonic anti-ship missiles.

Hypersonic flight is not a new thing. Even the Nazi V-2 rocket could break the Mach 5 barrier. What has changed, however, is the ability to control flight at this rate of speed to a high degree of accuracy.

Does the U.S. have any hypersonic missiles?

Although the United States was once leading the way in hypersonic technologies, America’s defense apparatus has been so focused on counter-terror and counter-insurgency efforts throughout nearly two decades of combat operations that America’s hypersonic efforts were left to stagnate. Today, America has no hypersonic missiles in service, but there are a number of programs in development.

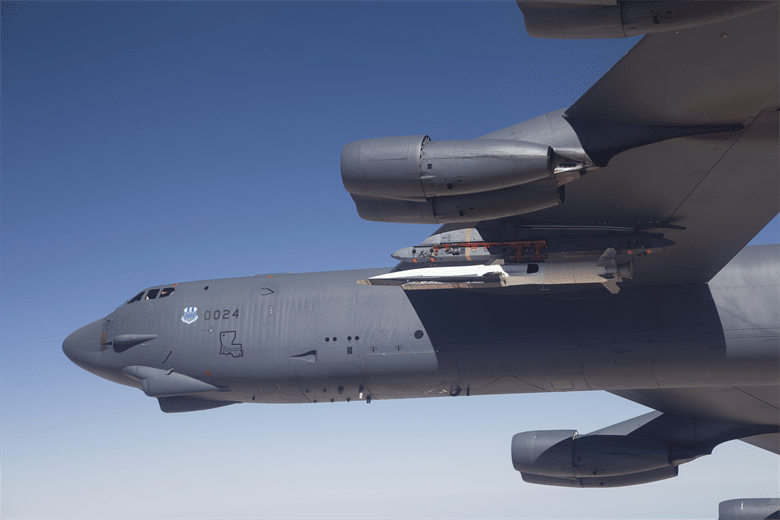

Lockheed Martin currently has four separate hypersonic weapons in development, including the Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) and the Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon (HCSW). Raytheon also has a number of hypersonic weapons under development.

What’s the difference between a hypersonic glide vehicle and a hypersonic cruise missile?

When people talk about hypersonic weapons, they’re usually referring to one of two kinds: hypersonic glide vehicles and hypersonic cruise missiles. Glide vehicles aren’t all that different than the warheads on traditional long range ballistic missiles. They are carried into the upper atmosphere via high velocity boosters just like traditional ICBMs. The missile then deploys one or more glide vehicles that rely on momentum and control surfaces to manage their high-speed descent as they close with their targets.

Hypersonic cruise missiles, on the other hand, often rely on an advanced propulsion system called a scramjet. A scramjet, or supersonic combusting ramjet, is a variation on tried and true ramjet technology that allows combustion to take place with supersonic airflow. Because scramjets are really only efficient at high rates of speed, these missiles are often deployed from fast moving aircraft or rely on a different form of propulsion to get them to these speeds.

From there, hypersonic cruise missiles operate much like traditional cruise missiles–at least in theory. In practice, these platforms are far more difficult and expensive to build than traditional cruise missiles.

What threat do hypersonic missiles pose?

There’s already a concerted effort to identify and develop technologies aimed at countering hypersonic weapons, but to date, no reliable form of defense against these fast-moving weapons has come to light. In the mean time, the Pentagon has launched a number of new initiatives aimed at mitigating the threat posed by foreign hypersonic weapons.

One weapon, in particular, has been the focal point of numerous Navy and Marine Corps initiatives: China’s DF-ZF hypersonic anti-ship platform. These missiles have an operational range of nearly 1,000 miles, and provided they can get good targeting information from specially built supersonic drones China developed for that precise purpose, they represent a significant threat to American aircraft carriers.

This presents a significant problem for the American defense apparatus, because its primary means of force projection has long been carrier-based aircraft like the F/A-18 Super Hornet and the F-35C Joint Strike Fighter. These jets have a combat radius of only around 500 miles, which means carriers would have to come that close to China’s shores (and anti-ship missiles) to deploy aircraft.

What is the U.S. doing to mitigate these threats?

There are initiatives aimed at gauging the efficacy of using space-based weapons systems to intercept Russian missiles high in their ascent and before they can deploy hypersonic glide vehicles back down toward earth, but thus far, no program has been publicly funded.

In the case of China’s anti-ship weapons, however, a number of programs are already up and running. The Navy recently awarded a contract to Boeing to continue development on the MQ-25 Stingray, which is a carrier-based autonomous refueler drone. These drones will soon be launched from carriers to provide in-flight refueling to carrier-based combat aircraft, effectively extending the operational range of each by hundreds of miles.

Other initiatives include the Marine Corps training to establish austere airstrips on islands inside China’s anti-ship radius. These hasty airstrips would be utilized by vertical landing F-35Bs, where they could be rapidly re-armed and re-fueled to conduct repeated strikes against anti-ship and air defense systems.

Even the forthcoming B-21 Raider, said to be the stealthiest and most technologically advanced bomber ever built, could foreseeable help protect American carriers–by striking anti-ship platforms undetected by Chinese radar installations.

It seems clear at this point that there is no one solution to the hypersonic problem. Instead, managing this newfound threat will require new technologies and new strategies aimed at properly leveraging existing military tech.

Are any other countries developing hypersonic weapons?

To date, the only nations to publicly acknowledge hypersonic programs are the United States, Russia, and China–and for good reason. At hypersonic velocities, everything becomes more complex and difficult. At that speed, the friction created by moving through air would be enough to destroy most missiles, and accurately targeting enemy positions from hundreds or even thousands of miles away requires a great deal of expensive technology and the training required to leverage it.

What that all really boils down to is money. Only the U.S., China, and Russia have the background in ballistic and cruise missile technology, the money to invest in hypersonics, and the interest in pursuing them today. China has placed a large emphasis on establishing itself as a dominant military power, particularly in the Pacific, and Russia’s struggling economy still places a great deal of emphasis on defense spending.

However, like nuclear weapons, hypersonic platforms and their associated technologies (including more efficient scramjet propulsion systems) will eventually become less expensive and more pervasive. Unlike nuclear weapons, however, hypersonic missiles can be used in conventional warfare without the nuclear, political, and diplomatic fallout of a nuke. That means that as the technology becomes less expensive and exotic, it may be harder to keep hypersonic weapons from being developed or purchased by third party nations.

In a very real way, hypersonic weapons represent a new arms race between three global military powers. But it’s only a matter of time before other competitors show up.

Feature photo courtesy of Raytheon

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Breaking News

The AGM-181 LRSO missile will modernize America’s nuclear triad

Navy will soon announce the contract award for its F/A-XX 6th-generation jet, according to reports

America’s new air-to-air missile is a drone’s worst nightmare

What we can deduce about the Boeing F-47 and its capabilities so far

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page