In late December, on the anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birthday, China revealed not one, but two, new stealth aircraft to the world through, what appeared to be, a carefully staged series of test flights. These aircraft, despite each being distinct in their own ways, shared angular, stealthy features and a tailless design, prompting many online to refer to them as “6th generation” fighters, though to date, neither the Chinese military nor government have made any public statements about their roles or designations.

To some, this revelation conjured a sense of foreboding and even doom, as it seemed to suggest China’s efforts to field a 6th generation fighter are rapidly maturing while America’s own 6th-gen fighter, now 10 years into development under the name Next Generation Air Dominance, remains on hold pending some difficult budgetary decisions to be made by the incoming Trump administration.

Others, however, were quick to dismiss these new Chinese jets as little more than vapor-ware, making dismissing quips about “made in China” stickers and the nation’s well-established propensity for making technological progress more through espionage and theft than traditional research and development.

The truth, however falls somewhere in between these extremes: these aircraft mark a significant development in China’s rapid military modernization and aggressive expansionary goals, and while that significance shouldn’t be discounted, it shouldn’t be exaggerated either.

So let’s talk about China’s new stealth jets, what they really mean for America’s defense, and whether or not they could represent some serious new arrows in China’s quiver.

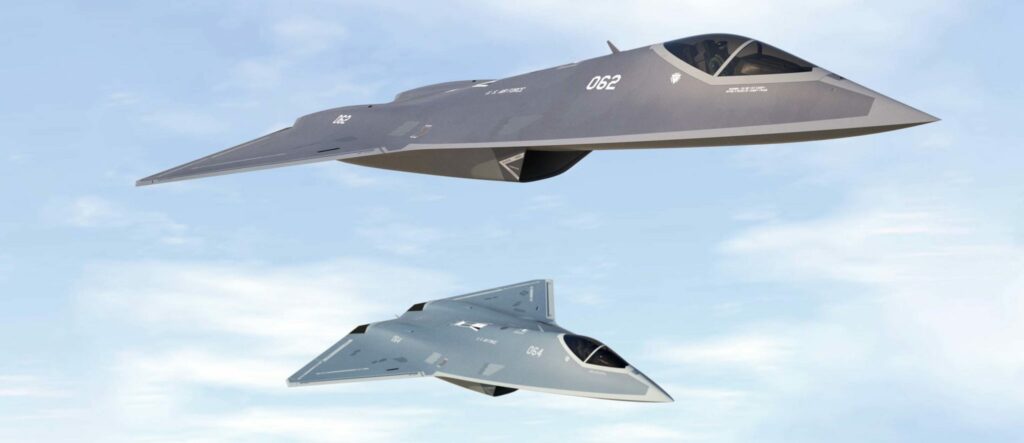

The delta-wing J-36

The first of these new stealth aircraft has reportedly been given the designation J-36, marking what would be the highest numerical designation for a Chinese fighter since the recently unveiled fifth-generation J-35. Seen accompanied by the world’s only two-seat stealth fighter, the J-20S, the J-36’s modified delta wing design seems reminiscent of the J-20 in the same way the developmental F-16XL was an extension of the original F-16 design. And indeed, that similarity may speak to the intended operational use case for this stealthy aircraft.

The General Dynamics F-16XL was a cranked-arrow-wing derivative of the F-16A that competed with the F-15E Strike Eagle in the mid-1980s for the U.S. Air Force’s Enhanced Tactical Fighter competition. And while the Strike Eagle ultimately won out thanks to its high performance and lower manufacturing costs, the F-16XL demonstrated just how valuable incorporating that broader wing configuration could be for certain kinds of mission sets.

The J-36’s center fuselage is directly reminiscent of those found on China’s existing J-20 and J-35, with slightly different intake design and larger overall size to accommodate larger payloads. However, from there, the design departs pretty dramatically from China’s previous stealth fighters.

WATCH⚡️

— WORLD AT WAR (@World_At_War_6) December 27, 2024

”NEW CHINESE FIGHTER JET SEEN OVER CHENGDU”

Mysterious aircraft bearing triangular tailless design sparks speculation that China has cutting-edge stealth and endurance capabilities

This is probably the maiden flight of China’s sixth-generation fighter jet. pic.twitter.com/txuIqzQL4H

Perhaps most notable about the J-36’s design is the lack of standing vertical tail surfaces. This design element is commonly associated with “6th generation” fighter designs and offers several advantages in terms of low observability, even if it comes at the expense of technical complexity and some reduction in aerobatic maneuverability.

Stealth fighters like America’s F-22 or China’s J-20 are generally designed to limit detection and targeting against high-frequency radar arrays that are capable of producing what’s commonly called a “weapons-grade lock,” or in other words, that have the fidelity required to guide a weapon into a target. Yet, some elements of traditional fighter designs meant to improve aerobatic performance, things like big gaping jet inlets and standing vertical tail surfaces, can sporadically produce a detectable resonance against lower-frequency radar arrays that, themselves, aren’t capable of guiding a weapon into a target. By combining high and low-frequency arrays, however, advanced air defense systems can potentially detect a stealth fighter via a low-frequency array and use that to orient their high-frequency one to reduce the time required to secure a lock when that stealth fighter closes to within the system’s targeting envelope. By eliminating those standing tail surfaces, a stealth fighter can reduce the threat posed by these sorts of systems.

Eliminating those surfaces also dramatically reduces the aircraft’s radar return from angles other than head on, making it more difficult to detect and target from the side. This “all aspect” stealth has also been depicted in renders released depicting the U.S. Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance Fighter and the U.S. Navy’s F/A-XX fighters respectively.

But while the tailless design might be the first to catch your attention, the J-36’s unique engine layout is arguably the most unusual aspect of this aircraft — and may be the most telling about its intended role. Unlike China’s J-20 and J-35, both of which are twin-engine stealth fighters, the J-36 carries three engines — two are seemingly fed air through intakes on either side of the fuselage while the third intake is positioned atop the aircraft. At the rear, each of the three engines exhausts through outlets that look to be similar to those found on Northrop’s YF-23, which suggests a lack of thrust-vector control, which is the ability to orient the outflow of thrust independent of the aircraft, but offers a reduction in both radar and infrared detectability. However, the trailing edge of the aircraft is chock-full of moving control surfaces, including segments behind the trough-style exhaust outlets, potentially giving it some minimal degree of thrust vectoring capabilities, which could benefit flight control at high altitudes where thinner air limits the efficacy of standard control surfaces.

エンジン3発でダブルタイヤの全翼

— 名無しの政治将校 (@bandainokairai1) December 26, 2024

なぁにぃ、コレぇ pic.twitter.com/Id5ZmaSK3F

It’s currently believed that these three engines are likely WS-10Cs — the same interim engine currently powering China’s J-20 fleet. Though famed aviation journalist Bill Sweetman has rightly pointed out that it’s at least possible that the third, center-mounted engine may be a higher-bypass design meant to allow for better performance at high speeds and altitudes, though, Sweetman also points out, that this would be quite the logistical headache to support. It’s also possible that the two outer engines could provide differential thrust to aid in maneuvering.

Nonetheless, this aircraft’s delta-wing design and three-engine arrangement clearly point toward prioritizing high-speed, high-altitude flight over longer ranges than any existing Chinese fighter. The payload bay, which like the fuselage itself is similar to that of the J-20, appears to be longer and as Thomas Newdick and Tyler Rogoway have pointed out, is all but certainly deeper, allowing for not only larger payloads, but likely, the internal carriage of larger individual weapons. In short, this all points toward an aircraft meant to engage adversary targets at significant ranges, leaning on advanced avionics and low observability, rather than aerobatic performance, to win air-to-air fights.

Because of this emphasis on longer ranges and larger payloads, some have wondered if this aircraft may not be a fighter at all, and might instead be the product of the JH-XX program that aimed to field a regional bomber. Yet, that seems somewhat unlikely as it’s believed the regional bomber program is being headed by China’s Shenyang corporation, while this aircraft seems to operate out of the Chengdu Aircraft Corporation’s (CAC) headquarters in Chengdu, China.

But the J-36 wasn’t the only new stealth aircraft China revealed on Mao’s birthday, and just hours after its first images surfaced online, it was joined by another as-yet-unnamed stealth aircraft with a different, tailless design.

This other stealth aircraft appears to be the product of the aforementioned Shenyang Aircraft Corporation, which was also behind the development of the recently unveiled J-35. This twin-engine platform carries a variation of a lambda wing design, which does offer some benefits over a trapezoidal delta wing, including increased aerodynamic efficiency, but does increase manufacturing complexity and traditionally requires increased weight in the form of structural reinforcement.

It isn’t clear whether this aircraft is a drone of if it does indeed have a cockpit, but its use of two engines and lighter landing gear than the J-36, as well as its smaller overall size, all point toward a more conventional role. Like the J-36, however, its tailless design could improve the aircraft’s all-aspect stealth.

Related: Stolen stealth fighter: Why China’s J-20 has both US and Russian DNA

Does this mean China has taken the lead in fighter development?

By most accounts, both of these aircraft made their first flights in December 2024 and with no official statements regarding their programs, appear to be in the earliest stages of testing. China’s J-20, for instance, made its first flight in 2011 and saw six years of concerted development before entering service in 2017. The J-35 (or the FC-31 its derived from) saw its first flight in 2012 and is currently projected to enter service in 2026. Today, there are believed to be just three flying prototypes associated with the FC-31/J-35 program.

But even doing that sort of math may be getting ahead of ourselves. We currently don’t know whether these aircraft are the equivalent of American X-Planes, or experimental aircraft never meant to go straight into service at all, but rather serve as testbeds for emerging technologies to be integrated into later designs. They could also be technology demonstrators which are meant to demonstrate and mature technologies. Of course, they could be prototypes of new fighters meant to enter service in a similar form to how they look today, but even prototypes often see significant design revisions before making their way into service, particularly when bringing new technologies to bear.

What we’re seeing in these pictures and videos out of China are the technological equivalent of newborn babes that still have a lot of maturing to do before they can offer any kind of tactical or strategic value to China’s military. In fact, despite their significant differences, these aircraft may even be competing for budget allocations, meaning only one may ultimately find its way into service.

Which, of course, brings us back to what the internet really wants to talk about: whether these new Chinese fighters mean China has surpassed America’s airpower technology and will soon emerge as the first nation to field a 6th generation fighter. The truth is, fighter generational designations don’t actually mean much at all, and there are no universally accepted definitions for any generation, let alone the technology required to justify a “6th gen” moniker. But semantics notwithstanding, it’s important to understand the difference between showing new aircraft designs… and having them.

America began its early developmental efforts toward fielding what you might call a “6th gen” fighter all the way back in 2014 with the commissioning of a study entitled, “The Dominance Initiative.” By 2020, this effort had already produced at least one flying technology demonstrator that, according to former Air Force official Will Roper, had already set some kinds of performance records. It’s now understood that this effort, now known as the Next Generation Air Dominance program, has produced at least three flying prototypes and that a production contract would have been awarded in 2024 to actually start building these jets had the Air Force not found itself in a budgetary hole it couldn’t fight its way out of.

Ultimately, there’s no way for us to know by looking at China’s aircraft in testing if they’ve managed to bridge the tech divide in terms of avionics, long-range kill webs, and most importantly, in the functionality of AI-powered wingmen meant to fly alongside these crewed aircraft. But even if we give China the benefit of every doubt and assume its hardware and software is every bit as capable as the systems found in America’s top-tier fighters, that would still place China roughly four years behind America’s 6th gen fighter efforts in the best of circumstances.

That is… if America’s NGAD and F/A-XX programs do continue as intended, anyway.

But even if China does win the race to fielding new fighters before American or European efforts, that’s not necessarily a victory either as being the first to claim new technologies are in service will win you headlines, but fielding the right new technologies will win you wars.

So, while China’s new stealth jets don’t pose the kind of threat that could make this writer lose any sleep at night, they do serve as a powerful reminder of what Marine general and former Defense secretary James Mattis said: “America has no pre-ordained right to victory on the battlefield.”

If the American way of war is to continue relying on air supremacy, America will need to invest accordingly.

Feature Image: Image of China’s newly unveiled aircraft. (Photo South China Morning Post via Weibo/师伟微博)

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Russia has been suffering huge casualties but this shouldn’t matter

- Congress demands answers on low testosterone issues among special operators

- What it’s like to visit Korea’s Demilitarized Zone

- Space Force to deploy new jammers to yell at enemy satellites

- Ukraine peace negotiations don’t look promising