The true story of the ‘Red Baron’ is crazier than fiction

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Legends about the “Red Baron,” Germany’s most prolific fighter ace of World War I, are so pervasive in the world’s culture at this point that some people may believe the man and his exploits were nothing more than legend. The truth is, the Red Baron was very real, and his story may be even crazier than the legends that surround the name.

Born a Prussian aristocrat

On May 2, 1892, Major Albrecht Philipp Karl Julius Freiherr von Richthofen (that’s all one name) and his wife, Kunigunde von Schickfuss und Neudorff (also one name) had their second child–a son by the name of Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen. Born into wealth and aristocracy, the youngest Richthofen made it clear from an early age that he had no intentions of resting on the laurels of his family name. He not only took to horse riding and gymnastics, for which he earned a number of awards, he also spent a lot of time hunting animals from elk to wild boar. Once his younger brothers were born, it wasn’t long before Richthofen had them trailing behind him on his hunts as well.

By the time he was 11 years old, however, young Richthofen was sent off to a military academy in Schweidnitz (in what is now Poland). For the next eight years, he would prepare for a life of military service, which could be seen as either a good or bad turn of luck, as he graduated from his training in 1911, just three years before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand would plummet Europe into the world’s first Great War.

Richthofen was commissioned as an officer in the 1st Uhlan cavalry regiment of the Prussian army. Uhlan cavalry units were lighter and faster than the heavy cavalry of wars long past, but in many ways, they still closely resembled cavalry units of antiquity; often carrying lances and sabers into battle alongside their pistols.

Before he was the “Red Baron,” Richthofen fought on the front lines

Fighting far beneath the skies he’d go on to dominate, Richthofen served primarily as a cavalry reconnaissance officer, seeing intense combat on both the Eastern and Western fronts. Perhaps aided by his years on horseback as a youth, Richthofen set himself apart from his peers during these combat operations, earning an Iron Cross for his courage under fire during an engagement with Allied troops.

Related: The brutality of trench weapons in World War I

But times were changing, and with them, the way nations waged war. The muddy trenches that would come to symbolize the brutal fighting of World War I made cavalry on horseback increasingly irrelevant, and in order to find a better way to utilize cavalry troops, they were taken off of their horses and were assigned roles like dispatch runners and telephone operators. Before long, the up-and-coming Richthofen was given a new set of orders–to go work in the Prussian Army’s supply branch.

Richthofen, however, had no intentions of leaving the war behind for a safer position overseeing shipments of equipment and supplies. Disheartened, he wrote a letter to his commander requesting a transfer to a different kind of unit: the Imperial German Air Service.

From backseat observer to Germany’s highest-scoring living pilot

Related: The first US air to air kill was in a French airplane

In June of 1915, Richthofen made his first big leap toward Red Baron infamy when his request for transfer was approved. However, instead of shooting down Allied planes, the Air Service stuck the young man in the back seat of a reconnaissance plane in the role of “aerial observer.”

By the end of the summer, however, he was sent back to the Western Front, where he trained to become a full-fledged pilot himself. After flying multiple combat missions over France and Russia, the cavalry scout-turned-pilot began to catch the attention of other German aviators. One such aviator happened to be one Oswald Boelcke, a famous flying ace with dozens of Allied kills to his name. Boelcke wasn’t just an expert pilot, he was a highly capable leader and tactician, known today by some as the “Father of Air Fighting Tactics.”

Boelcke saw Richthofen’s potential and recruited him into his new fighter squadron: Jasta 2. With the experienced pilot’s guidance, Richthofen quickly became a formidable pilot, earning his first kill on September 17, 1916 when he shot down a British aircraft over France.

“I gave a short series of shots with my machine gun,” he later wrote of the dogfight.

“I had gone so close that I was afraid I might dash into the Englishman. Suddenly, I nearly yelled with joy for the propeller of the enemy machine had stopped turning.”

In order to be considered a flying ace, a pilot needs to down five enemy aircraft. By Spring of the following year, Richthofen had already shot down 16. Four of them even came in just one day.

Unfortunately for Richthofen (but maybe fortunately for the Allies), his flying ace tutor, Boelcke, was killed after a mid-air collision with a friendly aircraft in 1916. Boelcke had accrued a whopping 40 air victories before he died, but his greater impact may have been in his tutelage of pilots and his skill as a tactician. Of the 15 pilots Boelcke recruited for his unit, eight would become flying aces and three would go on to command Jasta 2 themselves. By the end of the conflict, the unit would produce 25 such aces, four of whom would go on to serve as generals under the Nazi regime in World War II. Remarkably, Boelcke was only 25 when he died.

The birth of the Red Baron

With Boelcke gone, Richthofen’s 16 kills made him Germany’s highest-scoring living pilot, earning him Germany’s most prolific military medal, the Pour le Mérite, and command of his own squadron, Jasta 11. Surprisingly, one of Richthofen’s younger brothers who used to follow him into the woods to hunt elk, Lothar von Richthofen, was one of the pilots under his command.

Soon thereafter, Germany’s most prolific flying ace made a dramatic decision: he chose to paint his Albatros D.III fighter plane blood red. Almost immediately, the skillful pilot was given a number of monikers highlighting his prowess as well as his flair for the dramatic. Some called him “le Petit Rouge.” Others called him “the Red Battle Flier” or the “the Red Knight.”

But the rest of the world knew him as the Red Baron.

With a team of fighters to lead, Germany’s Red Baron set about making his previous exploits at the stick of his fighter seem practically mundane. Flying his blood-red Albatros D.III, Richthofen lived up to the hype surrounding him, shooting down two dozen enemy aircraft in April of 1917 alone. With a total of 52 kills under his belt, the Red Baron was quickly becoming a celebrity–and a favored tool of the German propaganda machine.

Collecting trophies as well as kills

Despite his fame, Richthofen was no showboat at the stick of his aircraft. He may have painted his plane bright red to stand out, but his approach to combat was that of a skilled tactician–and just as importantly–a team player. The feared Red Baron wasn’t doing high-flying acrobatics and diving into fights on his own. Instead, he flew and fought in formation and worked together with his wingmen to set traps for Allied aircraft.

With each enemy plane Richthofen shot down, he would commission a small silver cup from a local jeweler, but as his trophy-cup collection topped 60, the jeweler had to start turning down his orders due to silver shortages. Undeterred, the Red Baron had other means of recounting his victories.

Before long, his home was adorned in trophies symbolizing his conquests in combat and in hunting. Animal heads hung from the walls alongside souvenirs he’d taken from the wreckage of Allied planes he’d shot down. Fabric serial numbers, cockpit instruments, and even aircraft machine guns all found their way into his growing collection. He even had a chandelier made for his home out of the engine from a French plane he’d shot down.

With command of his own fighter wing, comprised of four squadrons, Germany’s Red Baron was given yet another nickname. His fighter wing, complete with brightly colored aircraft and legendary combat exploits, came to be known as “the flying circus,” and Richthofen as the circus’ “ringmaster.” Amid his trophy-laden house, the pilot would pile sacks of fan mail and hold interviews with prominent newspapers.

Not even being shot in the head could stop the Red Baron

Despite his growing legend, the Red Baron was still nothing more than Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen. He may have been a wealthy aristocrat and a war hero in his nation, but behind the trophies, the bravado, and the stick of his plane, sat a man made of flesh and blood. On July 6, 1917, Richthofen was given a polite reminder of that at the hands of a British F.E.2 biplane.

A single bullet tore through Richthofen’s red fighter, grazing his head and fracturing his skull. The impact of the round left him suddenly blind and paralyzed, but before the aircraft careened into the ground, the seasoned pilot regained his senses and was able to manage a rough landing behind the German lines. The injury left Richthofen with terrible headaches, nausea, and serious bouts of depression–but it wasn’t enough to keep him from the fight. Despite being ordered by doctors not to return to active duty, the Red Baron was once again terrorizing the skies the following month.

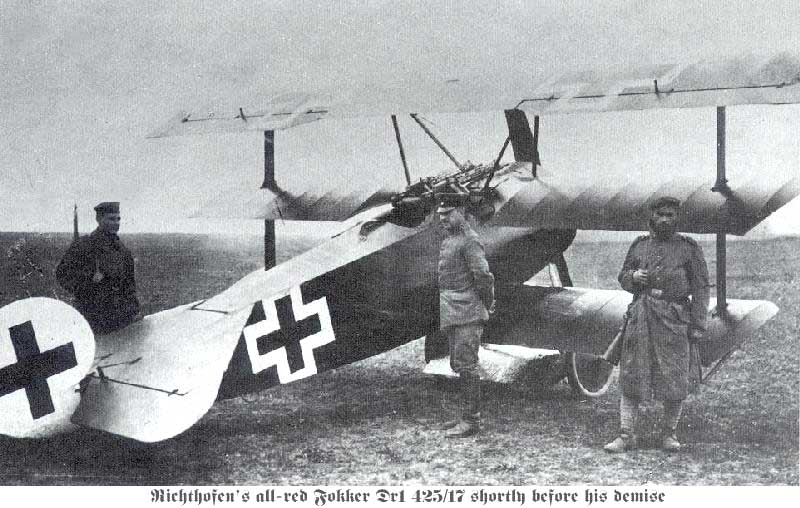

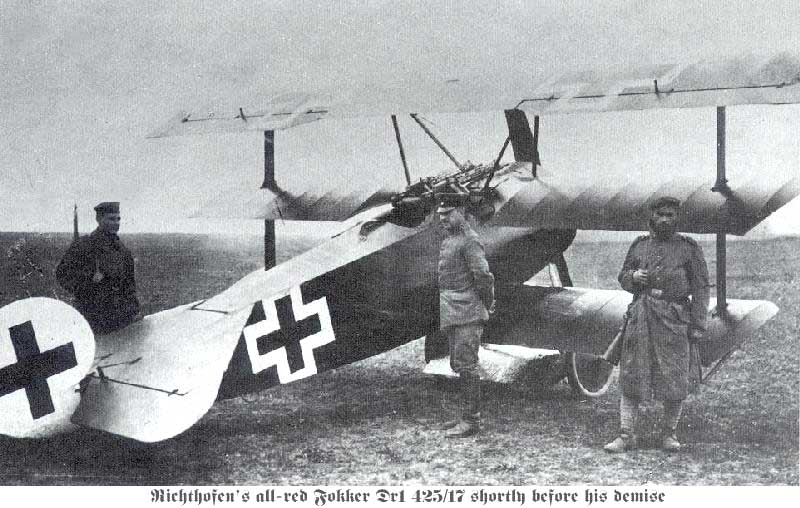

Not long after returning to duty, Richthofen upgraded to a more acrobatic Fokker Dr.1 triplane–the plane that would become synonymous with the Red Baron legend. Despite. his injuries, he returned to the fight with renewed vigor, quickly racking up kills in his new fighter. By April of 1918, the Red Baron had an incredible 80 kills to his name.

The Red Baron’s luck runs out

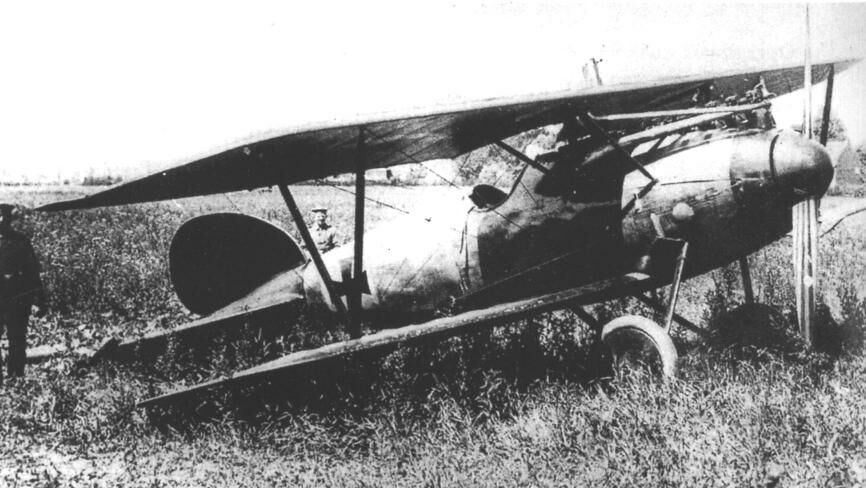

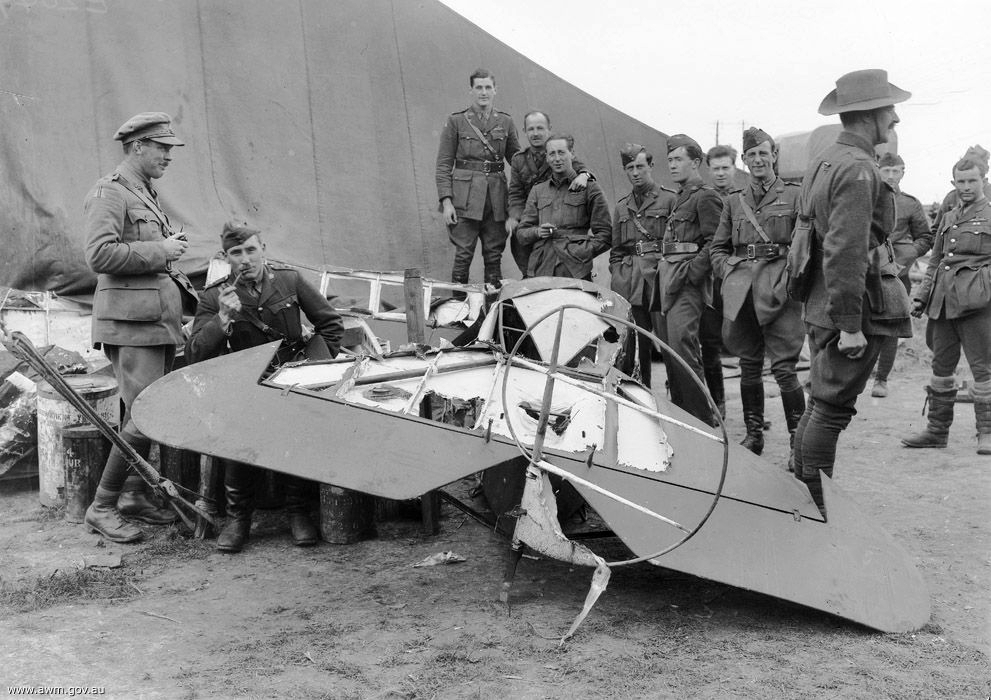

On April 21, 1918, one day after shooting down his 80th Allied aircraft, Richthofen led his “Flying Circus” into battle over Vaux-sur-Somme in northern France. They were met by a wave of British fighters, and Richthofen almost immediately gave chase to a Sopwith Camel piloted by a young and inexperienced Brit named Wilfrid May. It was an acrobatic chase like literally dozens he’d flown before, but as the blood-red Fokker tri-plane zoomed low over Allied infantry troops, a group of Australian soldiers spotted the infamous German pilot.

They opened fire as the Red Baron passed over their heads. At the same time, Canadian Captain Arthur Roy Brown, May’s squadron leader, got into position behind the red-painted fighter and squeezed the trigger, unleashing a hail of gunfire into the Fokker triplane’s tail.

It’s unclear who’s gun actually hit Richthofen, but a single round tore through his torso. Unlike the previous time he’d been hit, Richthofen failed to recover the aircraft. He crashed in a nearby beet field, where he would bleed out and die, still strapped to his seat.

Just like his flying ace tutor Boelcke before him, the Red Baron was dead at only age 25.

Seven months later, Germany would sign the Treaty of Versailles, admitting defeat to the Allied powers.

Read more from Sandboxx News:

This article was originally published 3/19/2021

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart -

A-10 ‘Warthog’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Military History

How US Special Forces took on Wagner Group mercenaries in an intense 4-hour battle

F-16s carrying the A-10’s 30mm cannon actually saw combat

How does China’s new J-35 stealth fighter compare to America’s F-35?

Why China’s new J-35 jet could mean trouble for America

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page