The S&W Light Rifle – The little carbine that could

- By Travis Pike

Share This Article

Light rifle is an interesting term. It’s a designation we don’t use much anymore solely because it’s obsolete in the face of the modern assault rifle. In 1939 the light rifle was a very real thing and was a concept being tested and evaluated for modern warfare. America eventually adopted a light rifle, the M1 Carbine. However, it wasn’t the only light rifle, and in 1939 Smith and Wesson developed the S&W Light Rifle.

Officially it’s the Smith and Wesson Model 1940 Light Rifle, but that’s a mouthful, so we’ll call it the S&W Light Rifle. Unlike the M1 Carbine, the S&W Light Rifle didn’t use a cartridge that fell between a rifle and pistol cartridge. S&W just went with the classic 9mm round that had been around since 1902.

S&W designed its rifle in 1939 and submitted it the same year to military testing at the Aberdeen Proving Ground. We can assume the rifle performed fine because the military noted they weren’t interested because, firstly, it was a 9mm, which was not a U.S. Service cartridge at the time, and secondly, it didn’t permit full-auto fire.

The military suggested resubmitting a full-auto version for testing, but it doesn’t seem like S&W ever did. A 9mm cartridge also took it out of the light rifle running, due to its effective range. (The .30 carbine could reach out to 300 yards or so, whereas the 9mm struggles at 100 yards.)

It was a gun without a real purpose. Yet, that didn’t mean S&W didn’t want those military contracts.

Breaking down the S&W Light Rifle

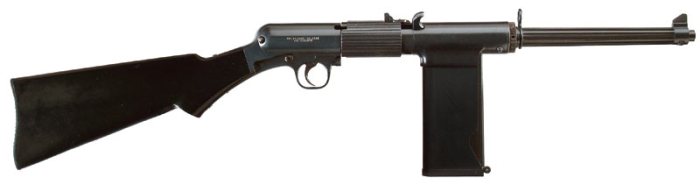

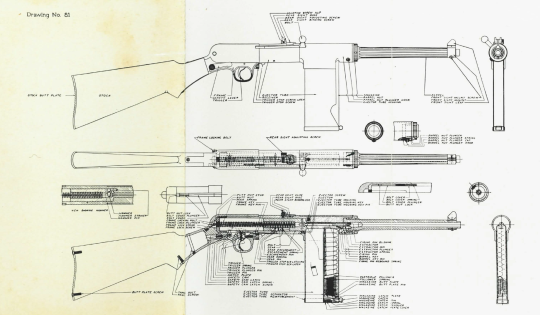

The S&W Light Rifle is an odd duck. It’s a semi-auto-only rifle that fired from an open bolt and fired the 9mm Parabellum cartridge. Open bolt designs are typically used with the submachine guns of the era to permit a simple but reliable design to provide full-auto fire. Open bolt, semi-auto rifles have all of the downsides of an open bolt design without any of the upsides of the design.

The downsides are less reliability, a shifting forward weight that causes some accuracy issues, and an open action that gathers gunk and debris.

Smith and Wesson went with a 9.75-inch barrel that’s completely reasonable for the gun and an overall length of 32 inches. The rifle had a fixed stock made from Tennite, a polymer material, which is an interesting choice and a somewhat rare one for 1939.

Although the S&W Light Rifle has light in the title, that referred to the cartridge the gun chambered. This rifle wasn’t light, and it weighed over 9 pounds unloaded. For comparison, an M4 weighs 6.43 pounds unloaded.

Related: How the M16 rifle gave birth to the M4 carbine

Diving deep into the S&W Light Rifle

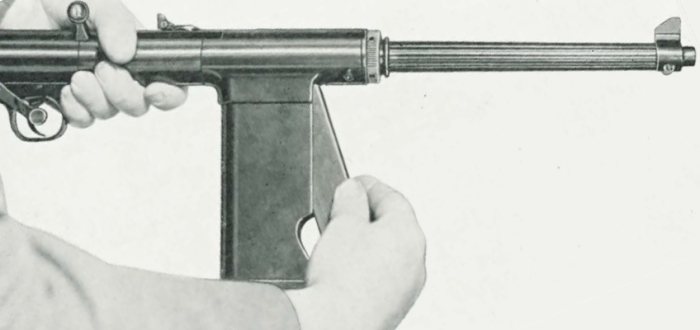

When you look at the S&W Light Rifle, it seems like the magazine is huge. However, that’s not the magazine. It’s a magazine tower. The magazine is a standard 20-round, double stack, double feed magazine that fits in the front of this tower. The rear portion of the tower acts as an empty case guide and ejection port.

This ensures the rounds eject downward and not to the side. That could be handy, especially in armored vehicles or in tight quarters. However, the magazine tower had some issues. First, if it got clogged up by dirt, mud, debris, or whatever, it would cause failures. Second, if you got a complicated malfunction, it was difficult to fix without field stripping the gun.

Smith and Wesson produced two different models, and the differences were subtle. We had the Mk1 and Mk2 models. The Mk1 featured a lever-style safety positioned behind the trigger. The Mk2 featured a safety that rotated around the charging handle and locked the bolt in place. These sleeves would supposedly make the receivers stronger.

Across the top, we had a set of open iron sights. The sights were simple and optimistic, with settings out to 400 yards. That’s an insane range for 9mm.

Smith and Wesson went with a heavy-duty barrel; an odd choice for a 9mm rifle. That heavy barrel was fluted to reduce weight. That fluting and heavy barrel made the weapon expensive and heavy. It’s an unusual choice with no real benefits for a 9mm rifle and had the downsides of being off-balanced.

Related: The Hi-Power – A legendary handgun

To the front… kind of

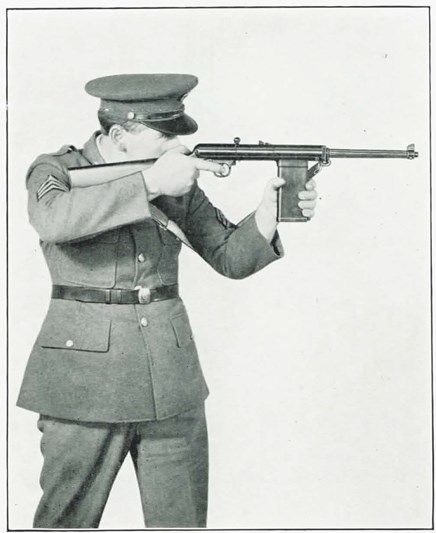

The U.S. Army had no interest in the S&W Light Rifle, but with the Nazi menace on the rise, the Brits were gun shopping. S&W offered them the S&W Light Rifle, and they were all about it. They needed guns and needed them badly, so they put down a deposit of approximately one million pounds.

S&W began shipping them rifles, and the British Armed Forces wisely decided to test them. They put them through an endurance test of 5,000 rounds. The S&W Light Rifle failed. It began shooting itself to pieces, cracking receivers, and more. This led to the Mk2 version with the sleeve, but the problem persisted.

It wasn’t because Smith and Wesson made crappy guns. It was because the Brits used hot ammo. In fact, it was loaded to be two grains hotter than the ammo S&W used to produce the rifle. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but it makes a big difference in pistol rounds. The Brits would later have to separate SMG and handgun ammo to keep handguns from blowing up.

Nevertheless, the British wanted that money back. Yet, Smith and Wesson had already spent the money to produce the tooling for building the S&W Light Rifle. This put both parties in a pickle, but an arrangement was reached, whereby S&W would produce and send revolvers to cover the cost.

The end of the light rifle

Most of the S&W Light Rifles were destroyed, and only 1,227 were ever produced. Less than 300 exist to this day. They are valuable collector’s items and fetch a rather high price.

The S&W Light Rifle was a mess. It was a heavy, semi-auto-only rifle with a weird magazine tower and firing a pistol cartridge from an open bolt with a heavy barrel. The design choices were odd, and the S&W Light Rifle predictably failed, although it left an odd mark on small arms history.

Read more from Sandboxx News

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Travis Pike

Travis Pike is a former Marine Machine gunner who served with 2nd Bn 2nd Marines for 5 years. He deployed in 2009 to Afghanistan and again in 2011 with the 22nd MEU(SOC) during a record-setting 11 months at sea. He’s trained with the Romanian Army, the Spanish Marines, the Emirate Marines, and the Afghan National Army. He serves as an NRA certified pistol instructor and teaches concealed carry classes.

Related to: Military History

5 ways to prepare and survive the Marine Corps boot camp

Barrett’s Squad Support Rifle System will make infantry squad deadlier

The unique world and uses of howitzers

How close are the Colonial Marines from ‘Aliens’ to actual Marines

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page