THE NAVY’S PLAN TO FLY THE C-130 OFF AIRCRAFT CARRIERS (THAT WORKED)

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

The U.S. Navy once experimented with landing a full-sized Lockheed C-130 Hercules on an aircraft carrier to offer a flying option for heavy resupply missions at sea. The craziest part of the plan was that it totally worked.

Why try to land a C-130 on an aircraft carrier?

America’s Nimitz and Ford-class supercarriers make up the backbone of what could be described as the U.S. Navy’s “blue-water” force. In common discussion, a “green water” navy is largely relegated to littoral, or coastal, operations because of its reliance on frequent resupplies from nearby friendly ports. A “blue water” navy, on the other hand, has the ability to operate globally, leveraging a combination of friendly ports and at-sea replenishment to keep each warship adequately fueled and supplied.

These supply shipments often come during port stops or from other ships while at sea, but those aren’t always readily available options. For carriers that are forward-deployed in combat operations, getting a heavy payload of essential parts or supplies to the ship quickly could mean the difference between making mission and mission failure. For smaller jobs, Carrier Onboard Delivery aircraft (CODs) can make special deliveries, but by the early 1960s, it was becoming clear that the planes relied on for this role, like the Grumman C-1 Trader, just weren’t able to deliver some of the heavier parts or equipment a carrier might really need in a fight.

While the U.S.’ modern Nimitz and Ford-class carriers don’t require fuel for decades at a time, they still require all sorts of supplies from land-based installations, ranging from the common types of stuff you need to support the more than 3,000 troops on board, to replacement parts for the aircraft that operate from the carrier’s flight deck.

So the Navy set out to find a way to get larger shipments out to carriers at sea without having to devise an expensive clean-sheet aircraft for the job. After a bit of consideration, a solution that was just crazy enough to work emerged: Landing Lockheed’s four-engine C-130 Hercules right on the deck of an aircraft carrier.

Planes have to be built differently for carrier duty (except for the C-130, apparently)

Lockheed Martin’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is thought of as just one jet, but it’s actually three different aircraft. The F-35A and B are intended to fly from conventional airstrips and short or austere runways respectively, but the F-35C is the only variant rated for carrier operations. In order to understand why, you have to consider the incredible forces carrier aircraft are subjected to during take-off and landing.

Carrier-based fighters utilize steam or electromagnetic powered catapults to propel them to takeoff speeds in a fraction of the time normal aircraft climb into the sky. When landing, carrier-based aircraft deploy hooks to grab massive steel cables that arrest their forward movement almost instantly, despite pilots going to full-throttle upon touching the deck, just in case anything goes wrong.

Imagine taking a regular car and replacing its brakes with a steel hook you’ll use to catch a cable while traveling at 140 miles per hour. You’ll keep your foot firmly planted on the gas pedal throughout, but the cable will be strong enough to bring you to a sudden and violent halt nonetheless. Using such a hook system instead of your brakes is sure to break some stuff on the car… but now imagine if that was the only way you ever actually stopped. Such is the engineering challenge of designing a fighter that can not only duke it out in the skies, but also survive carrier landings and launches on a regular basis.

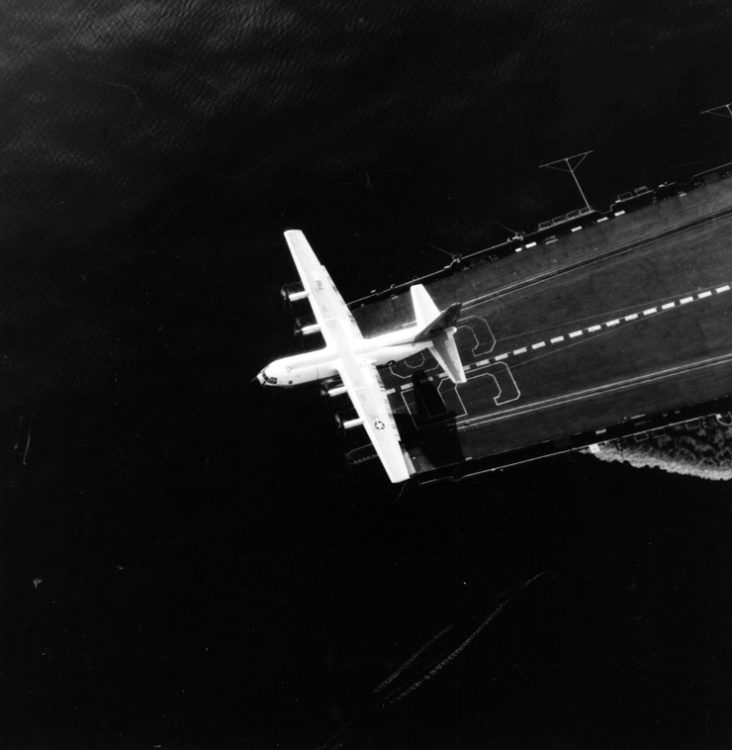

Carrier-based fighters tend to be heavier, because of their reinforced fuselages and tail hooks, but are expected to offer similar lifespans and reliability to their land-based counterparts. In a perfect world, Lockheed would have taken the Navy’s idea to land a Hercules on their carriers and devised an all-new C-130 airframe purpose-built for the rigors of carrier life. It’s not a perfect world, however, and funding was minimal… so the Navy opted to experiment with the concept using nothing more than a lightly modified Marine Corps KC-130F refueler transport. What it lacked in a carrier-specific design, it more than made up for in stability, payload capacity, and range–all of which were all too good for the Navy to ignore.

The only changes made to the mighty KC-130 were the installation of smaller nose-landing gear, an improved braking system intended to prevent skidding on the flight deck, and the removal of the aircraft’s underwing fuel pods. Beyond that, the first attempt at landing a C-130 aboard an aircraft carrier would come from an otherwise bone-stock aircraft never intended for such a feat.

“LOOK MA, NO HOOK”

Then Lt. James H. Flatley III was chosen for the historic first attempt at landing a C-130 aboard an aircraft carrier, and as may come as little surprise, he reportedly thought the Navy was joking when they gave him his orders. Flatley was a fighter pilot who had never even flown a 4-prop aircraft before.

Those seemingly hilarious orders, however, had come directly from the Chief of Naval Operations himself, and they were precisely as serious as the mission was dangerous. No one had ever attempted to land an aircraft as big as a C-130 on any of the Navy’s flattops before, and while success could mean a meaningful shift in how carrier resupplies were executed, failure would potentially mean death for Flatley and his crew.

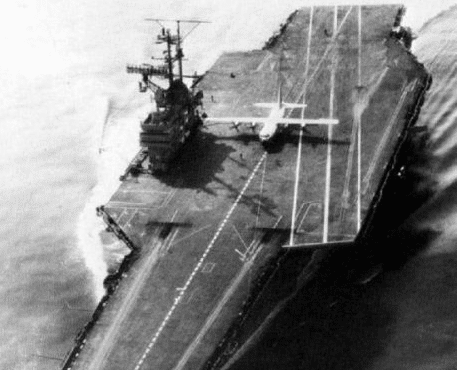

On October 3, 1963, the fateful day had arrived. Keen on not making this first test easy on anyone, the U.S. Navy had chosen the USS Forestal to receive the C-130 and positioned it some 500 miles off America’s Atlantic coast, near Boston. The waters were choppy, affecting the pitch of the deck, and Flatley faced 40-knot winds as he approached the 990-foot supercarrier.

The sea was pretty big that day. I was up on the captain’s bridge. I watched a man on the ship’s bow as that bow must have gone up and down 30 feet,†recounted Lockheed’s chief engineer, Art E. Flock, who was aboard to observe the test.

Flatley had done this approach as a fighter pilot countless times before, but the F-4 Phantoms in service with the U.S. Navy at the time boasted a wingspan of just 38 feet and a standard weight just north of 40,000 pounds. Now, Flatley was headed straight for the Forestal’s flight deck in a 4-prop C-130 with a wingspan that was nearly four times the size of the F-4.

As the big ship’s flight deck pitched and rolled with the Atlantic waves, Flatley brought his massive C-130 down onto the aircraft carrier with expert precision, missing the Forestal’s control tower with the edge of the plane’s wing by just 15 feet.

“That airplane stopped right opposite the captain’s bridge,†recalled Flock. “There was cheering and laughing. There on the side of the fuselage, a big sign had been painted on that said, ‘LOOK MA, NO HOOK.’”

Flying a giant from the open sea

That was far from the last time Flatley would fly the C-130 onto or off of an aircraft carrier. For the remainder of the month, he and his crew would execute a variety of flight operations from the Forestal, including 21 total full-stop landings without any need for arresting gear, and 21 more un-assisted take-offs from the same flight deck. On top of those flights, they also successfully executed 29 stop-and-go landings on the carrier, seemingly proving that, despite not being designed for the job, Lockheed’s C-130s were entirely capable of carrier duty.

In order to make the landings as short as possible, Flatley pulled from his fighter pilot tool box to execute a landing “chop,” which is effectively killing the aircraft’s engines while still a few feet off the deck of the ship.

Incredibly, while flying at 85,000 pounds (with very little cargo), the C-130 managed to come to a complete stop aboard the Forestal in just 267 feet. When they tried it again with a maximum payload, piling as much weight into the C-130 as it could manage, the cargo aircraft still stopped in a paltry 460 feet. Importantly, it could also take off from the Forestal’s flight deck with that much weight on board, needing only 745 feet for takeoff while weighing in at an astonishing 121,000 pounds.

“The last landing I participated in, we touched down about 150 feet from the end, stopped in 270 feet more and launched from that position, using what was left of the deck,” Lockheed’s Ted Limmer recalled.

“We still had a couple hundred feet left when we lifted off. Admiral Brown was flabbergasted.”

A rousing success that was still scrapped

Throughout dozens of test flights, the Navy gathered enough data to conclude that the C-130 really could fill the role of a heavy-lift Carrier Onboard Delivery aircraft. According to their data, the United States could fly 25,000 pounds of cargo up to 2,500 miles to a carrier at sea aboard a barely modified C-130, land, unload the goods, and depart again–all without the need for significant changes to the aircraft or the ship.

The intent was never to replace more efficient means of resupplying a carrier at sea, but rather, to offer the Navy a capable emergency option that could deliver whatever a carrier needed to stay in the fight without waiting on or risking other vessels. Flatley and his crew had proven it was possible, but it still wasn’t exactly practical.

In order to leverage the C-130 for carrier operations, the flight deck would need to be cleared, and as might go without saying, the C-130 pilot has to be at the very top of their game. Flatley may have managed to make the job look easy during his month of test landings and take-offs, but the truth was, there was nothing easy about landing such a massive aircraft on a ship out at sea.

Ultimately, the Navy opted to continue using smaller COD aircraft, as they could manage most deliveries a carrier would need. Flatley was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his part in the effort, and would go on to become a carrier commander himself, assuming command of the USS Saratoga, a Forestal-class carrier, in 1980.

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

A-10 ‘Thunderbolt Power’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Military History

How US Special Forces took on Wagner Group mercenaries in an intense 4-hour battle

F-16s carrying the A-10’s 30mm cannon actually saw combat

How does China’s new J-35 stealth fighter compare to America’s F-35?

Why China’s new J-35 jet could mean trouble for America

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page