Incredible true stories of Area 51: Hiding America’s air power secrets

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Nestled deep within the Air Force’s Nevada Test and Training Range, the remote and highly classified facility we’ve come to know as Area 51 has been the heart of secretive American aircraft programs – and a fair bit of modern folklore – for more than 50 years. This clandestine airbase, known in some official circles as Homey Airport or simply as Groom Lake, lies hidden within some 2.9 million acres of empty, mountainous, military-controlled territory that the Defense Department itself describes as “a flexible, realistic and multidimensional battle-space to conduct testing tactics development and advanced training.”

The sprawling runways and oversized hangar facilities of Area 51 are not only far removed from the prying eyes of the outside world, but exist behind multiple overlapping veils of security precautions, systems, and personnel.

This installation is so tightly guarded that the only way to access it is to fly in from the Harry Reid International Airport in Las Vegas, some 82 miles south, aboard one of the specially-crewed Beoing 737-66Ns or Beechcraft turboprop aircraft that make 10 round trip flights into and out of Area 51 each day for commuters. For those without an active security clearance and a good reason to visit, the best you can do is get a glimpse of 2.3-mile-long runways through powerful binoculars atop Tikaboo Peak, a mountain some 26 miles from the base.

Area 51’s remote location, difficult terrain, and military security were more than enough to keep the prying eyes of the public at bay when the base was originally built in the 1950s. Yet, the advent of spy satellites in the years that followed gave country-level adversaries the means to peer behind the curtain and directly into some of the nation’s most advanced, strategically valuable, and Top Secret defense programs.

Officially, the U.S. government didn’t acknowledge Area 51’s existence until 2013, but unofficially, the base was something of an open secret right from the start. So, when the Soviet Union launched their first “Zenit” spy satellites in the early 1960s, snapping pics of Groom Lake rapidly became among their primary photoreconnaissance duties.

As a result, while Area 51 might be known for its role in the development of some of the most advanced military technologies on the planet, the often uncredited but nonetheless hardworking men and women who work there quickly found several low-tech ways to mitigate, obfuscate, and even bamboozle their Soviet spectators.

Related: We asked AI to show us the secret aircraft hidden in Area 51

The down-to-earth origins of Area 51

On September 4, 1949, a B-29 Superfortress that had been specially modified for a weather-reconnaissance role (known as a WB-29) returned from a routine flight off the coast of Siberia with air samples showing anomalously high levels of airborne radioactive debris – high enough, that the only logical explanation was the detonation of new Soviet nuclear weapon. The detonation, American intelligence officials would come to learn, was of a roughly 20-kiloton weapon that the Soviet military had taken to calling First Lightning.

With memories of Pearl Harbor being recent, the American Defense apparatus went on high alert, scrambling to gather all the intelligence it could about the Soviet’s burgeoning nuclear weapons program and the possibility that the United States could be taken by surprise once again.

The challenge, however, was heightened by rapidly advancing Soviet air defenses, which were already capable of downing any American reconnaissance aircraft encroaching on their territory. To overcome this challenge, Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson proposed a new aircraft, loosely based on the still experimental at-the-time F-104 Starfighter, but with expansive glider-like wings that could allow it to cruise at altitudes above 70,000 feet. The design, known at the time as CL-282, would eventually become the U-2.

As work on this new high-flying spy plane progressed in April 1955, senior CIA officer Richard Bissell, Air Force Colonel Osmund Ritland, Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier, and Johnson himself set about looking for a location that could accommodate the long runways the plane would require, while still being remote enough to maintain the program’s extreme level of secrecy. From their vantage point in a small Beechcraft airplane soaring high above the Nevada desert, the group spotted what appeared to be an abandoned airstrip in the northeast corner of a stretch of land they knew to be the Atomic Energy Commission’s (AEC) Nevada Proving Ground.

The group discussed landing on the runway itself, but LeVier ultimately chose to set the Beechcraft down on an adjacent dry lakebed – which, the story goes, was a serious bit of good fortune. What they thought was an abandoned airstrip was precisely that, having seen use as part of a gunnery range for pilots during World War II. But over the intervening years of disuse, an ankle-deep layer of loose dust had blanketed the entire runway. Had LeVier attempted to land in the dry desert slush, it could have ended in disaster, with the mastermind behind modern military aviation and a bevy of senior Defense officials all killed in a crash so remote, it might have been days before their bodies were even discovered.

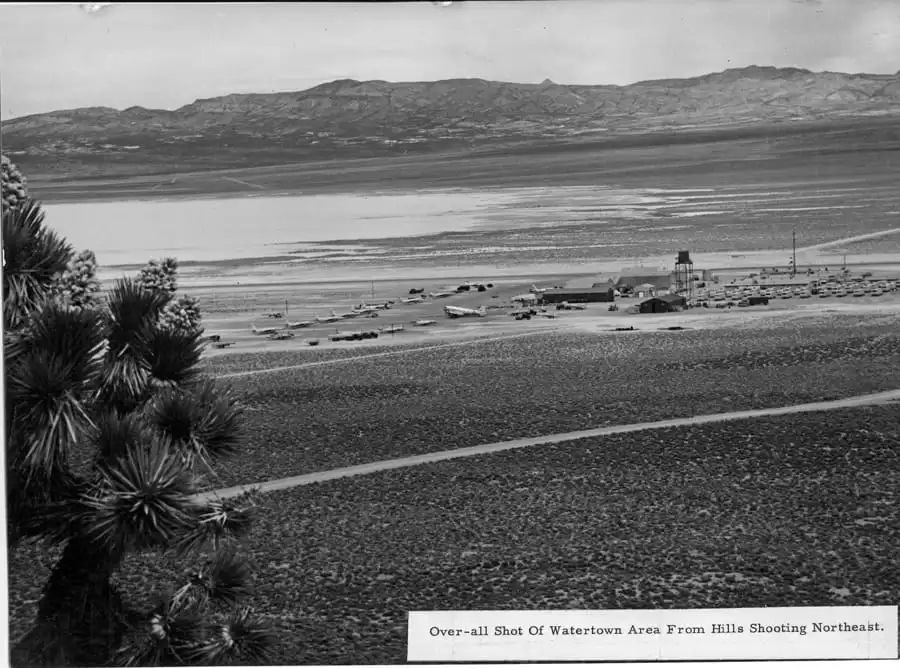

But despite the dust, the whole group quickly agreed that this desolate stretch of salt flats would be the perfect location to test America’s highly classified new aircraft, though they soon realized the salt flats alone would not suffice for aircraft testing. On the rare occasion that rain came through the area, runoff from the nearby mountains would flood the dry lake bed, making it impossible to take-off or land. This earned the remote installation one of its first unofficial nicknames: Watertown Strip.

To overcome this obstacle, an elevated and paved 5,000-foot runway was built alongside a slew of temporary hangar and workshop facilities over the following three months in preparation for U-2 testing.

But with blinding sun, little shade, and soaring temperatures, Johnson came up with a new name for their new secret base, Paradise Ranch, in part, because he hoped it would help sell the location to Lockheed personnel tasked with working out there.

On AEC maps, however, the location had a less descriptive numerical title – Area 51.

The growing importance of Area 51

By 1959, the U-2 spy plane had already been in service for four years, but Johnson knew its extreme altitude wouldn’t shield it from Soviet air defenses forever. As such, he had already gone through a dozen revisions on a new aircraft meant to replace the U-2; one that would marry high-altitude flight with sustained speeds no aircraft had ever achieved before. He called this new concept Archangel and abbreviated its 12th version to simply, A-12.

Johnson’s new spy plane would scream across the sky at three times the speed of sound and boast groundbreaking new radar-wicking design elements, electronic warfare systems, and even early radar-absorbent coatings to further complicate matters for Soviet air defenses.

Yet, the meager facilities of Area 51 were far from sufficient to support the testing of this groundbreaking new aircraft: The facility’s spattering of structures blurred the line between temporary and permanent, with only enough space for 150 or so people to work indoors in extremely cramped conditions.

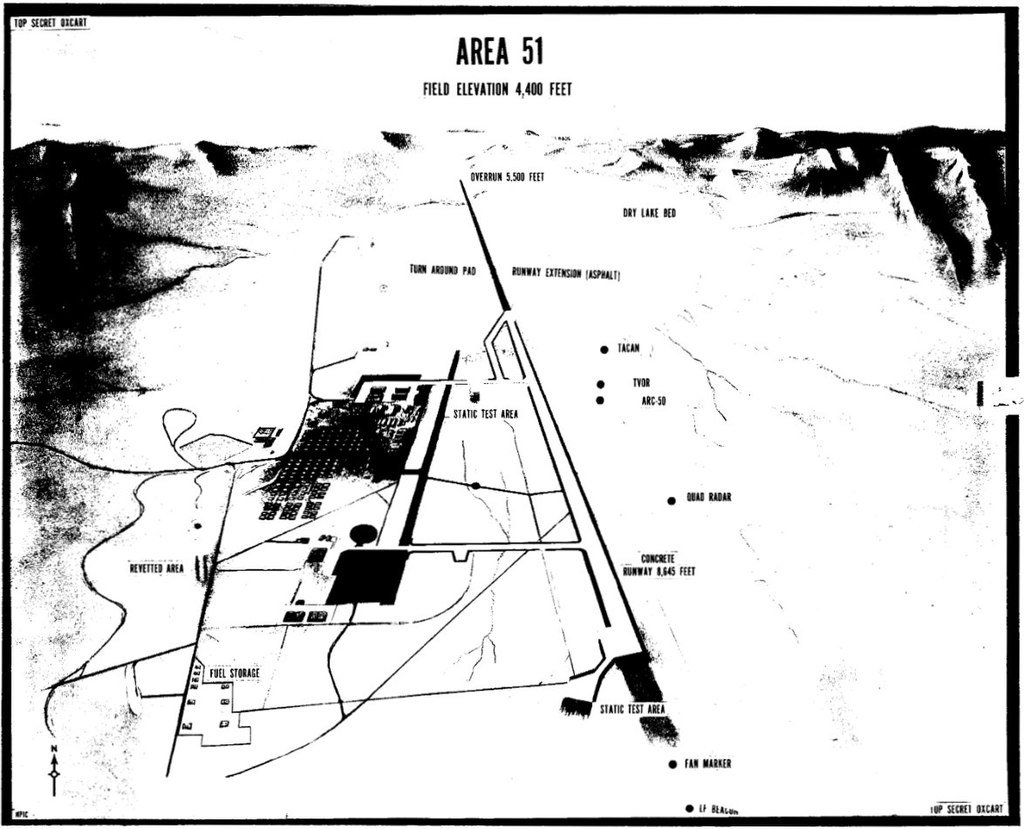

In September 1960, four months after the first U-2 was shot down by the Soviet Union, construction began to prepare Area 51 for a new era in high-performance aviation testing.

The previous 5,000-foot asphalt runway was not only too short, but couldn’t even support the weight of the new A-12 prototypes, so the first order of business was to lay down a whopping 25,000 yards of concrete to establish a new 8,500-foot runway. This monumental task was completed in just eight days.

Three surplus Navy hangars and over 100 surplus Navy housing buildings were dismantled from other locations, shipped in, and re-assembled in Area 51 for the facility’s personnel, supplementing and improving the existing facilities. Soon thereafter, a 1.32 million-gallon fuel tank farm was constructed to refuel the various aircraft flying out of the facility.

Johnson and his partners at the Air Force and CIA now had a state-of-the-art facility to test their new secret programs, far removed from ogling spectators, but their days of hiding out in the open were already numbered.

Less than two years later, on April 26, 1962, the Soviet Union launched its first successful spy satellite, the Zenit 2, and while this first Soviet foray into orbital espionage was only in orbit for three days, the United States knew it was only a matter of time before the Kremlin started taking pictures of the unacknowledged air base.

Related: The Soviets crashed into the moon while Apollo 11 was on it

The Ashcans are watching

That same month, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) drafted a document calling for the U.S. to use its U-2 spy planes or even America’s own (still-classified) spy satellite called CORONA, to photograph the base and assess what intelligence the Soviets might be able to glean about it from orbital altitudes.

“Without advising the photographic interpreters of what the target is, ask them to determine what type of activity is being conducted at the site photographed,” the memo read.

At the same time, U.S. intelligence analysts began tracking the orbital paths of Soviet satellites to provide Area 51 personnel with advanced notice of when they would be overhead the facility.

“In our morning security meetings, they’d give us a roster of the satellites that the Soviets had in the air, and we’d know the exact schedule of when they were coming over,” explained former Area 51 radar and hypersonic flight specialist Thornton “T.D.” Barnes in 2011. “It was like a bus schedule, and it even told us whether it was an infrared satellite or what type it was.”

Area 51 personnel like Barnes soon took to calling the Soviet spy satellites “ash cans” – a derogatory nickname meant to draw similarities between the orbital assets and common vernacular for trash cans at the time.

Usually, there was enough advanced notice of a spy satellite overhead to simply clear the flight line, tucking secret aircraft under hangars and awnings to block the Soviet’s view.

“That made the job very difficult, very difficult,” recalled Jim Freedman, who worked as a procurement manager at Area 51 alongside Barnes. To start working on the aircraft and then have to run it back into the hangar and then pull it out and then put it in and then pull it out – it gets to be quite a hassle.”

But when Barnes and his colleagues received a late warning, they found ways to improvise, building simple tent-like structures on poles they called “hoot and scoot sheds” they could quickly erect over an aircraft to hide it from Soviet cameras.

Related: SR-72? Hints of a new Skunk Works spy plane reignite rumors of a Blackbird successor

However, as is always the case in these high-dollar games of cat and mouse, the Soviet Union continued to look for ways to glean useful information from low-earth orbit. One 1964 CIA report on Soviet reconnaissance efforts argued that at least 20 percent of all funding going toward Soviet space programs at the time was specifically centered on the construction and launch of high-end spy satellites. Of the 16 total satellites the Soviets launched between 1962 and 1964, the CIA assessed that four were definitely spy satellites, eight others likely were, and only four were likely meant to fulfill the Soviet Union’s publicly disclosed scientific mission.

Among the long list of improvements the Soviets added to these overhead observers were infrared sensors that allowed their analysts to make out the overall shape of American aircraft that had been left sitting on the runway to bake in the glaring Nevada sun – even after they’d been moved into hangars to hide from the satellite as it passed by.

“It’s like a parking lot. After all the cars have left you can still see how many were parked there [in infrared] because of the difference in ground temperatures,” Barnes explained.

This posed a unique challenge to the personnel working at Area 51, who couldn’t avoid parking aircraft on the flight line as they conducted pre-flight inspections and the like. So, if they couldn’t hide the infrared shadows of their most secretive aircraft, they decided to muddy the visual waters by giving Soviet analysts a glut of aircraft designs to analyze.

Barnes and his colleagues at Area 51 gathered up huge swaths of cardboard and other mundane materials and carefully cut and crafted them into the silhouette of some sort of extremely exotic new aircraft. To make them seem as realistic as possible, they would even drag portable heaters out onto the flightline and run them right where the engines of their cardboard aircraft would be. Then, just before a Soviet “ash can” was set to zoom by overhead, they’d quickly drag all the cardboard, heaters, and whatever else they used back into a nearby hangar, leaving nothing but the infrared shadow of their cardboard bombers behind for Soviet analysts to pour over.

“We really played with the infrared satellites,” Barnes recalled.

This game of cat-and-mouse continues to this very day. In 2022, The Warzone published commercial satellite photos of the installation that showed a very unusual-looking aircraft parked on the runway in front of the facility’s newest hangar. The aircraft, however, is somewhat obscured by what certainly appears to be an updated iteration of the “hoot and scoot” sheds employed by Barnes and Co. back in the 1960s.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Shotguns are still relevant in modern warfare thanks to a new threat

- Video: Why there might never be a 7th-generation fighter

- How to avoid a 500lb bomb blast: A Delta Force philosophy on speed

- Video: When the US military tried to build a Fallout armor

- Remembering Saipan: The battle that reshaped the Pacific

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Military History

Just how good would an F-22/F-35 hybrid fighter really be?

What do we know about China’s new ‘6th gen’ fighters?

It doesn’t matter if China’s new J-36 stealth jet is a fighter or a bomber

Former Navy SEAL and pioneer combat medicine physician is awarded Presidential Citizen’s Medal

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page