The birth of stealth: How defeating radar became the way of war

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

In 1983, Lockheed’s dark and angular F-117 Nighthawk secretly entered service for the United States Air Force, silently becoming the world’s first operational stealth aircraft. The Nighthawk was like nothing the world had ever seen before, leveraging a faceted exterior surface and a coating of radar-absorbent materials meant to devour the inbound electromagnetic energy broadcast into space by air defense radar arrays. The stealth fighter, as it came to be known, wasn’t a fighter at all. It was an attack aircraft, purpose-built to deliver precision-guided munitions to targets deep inside enemy territory, leveraging a combination of technology and tactics to render even the most advanced surface-to-air missile systems harmless.

After decades of American and Soviet efforts to field higher, faster-flying aircraft as a means of increasing their survivability, the Nighthawk proved slow and sneaky was the way of the future.

Lockheed’s legendary Skunk Works division had changed airpower and the way it would be leveraged in war forever, under the watchful eye of engineer-turned-director Ben Rich. Rich was once known as the star pupil of Skunk Works founder Kelly Johnson, but in the years since the Nighthawk first took flight, he’s earned a different name in aviation circles – one the man himself might have shunned: the Father of Stealth.

It’s a worthy moniker for the man who had the foresight to invest Lockheed’s future into an unproven theory, taking a wad of Skunk Works cash and rolling it down a steep hill of never-before-seen technological challenges, collecting breakthroughs as it rolled until it grew too large to be stopped. Today, Lockheed Martin has claimed responsibility for a number of subsequent and even more advanced stealth platforms, including the world’s first real stealth fighter, the F-22 Raptor, and the most advanced tactical aircraft ever to fly, the F-35 Lightning II.

But as Rich himself explained in his book, Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed, stealth – or the means to deflect or delay radar detection and targeting – was much more than any one man’s initiative. It was the result of more than a century of mathematical, technological, and theoretical advancement.

There is no single father of stealth. But the concept can claim a long line of impressive uncles.

Related: Offsetting China’s stealth fighter advantage

An ignored Soviet paper made stealth much more feasible but didn’t invent the concept

The inception of modern-day stealth is often credited to the theoretical work of Soviet physicist and mathematician Pyotr Ufimtsev, whose book entitled, Method of Edge Waves in the Physical Theory of Diffraction had gone largely ignored by the Soviet Union since its publication in 1962. But this is a pretty significant oversimplification of stealth’s real birthright. In fact, by the time Ufimtsev’s book hit the printers, a number of stealth aircraft programs had already littered America’s expense reports. Convair’s Kingfish, a stealthy and triangular competitor for Lockheed’s famed SR-71, started preliminary design work in 1957.

Boeing’s Model 853-21 Quiet Bird was already being shaped, tested, and reshaped in front of radar arrays when the first copies of Ufimtsev’s book found their way into the hands of academics.

But that isn’t to say his work doesn’t deserve the recognition it’s received. In a real way, the work his own country overlooked became a vital piece of the puzzle that drew stealth out of the theoretical confines of project proposals and drawing boards. Ufimtsev’s work didn’t invent stealth, but there’s a reasonable argument to be made that he helped to make it economically feasible.

Related: Which will be the company that will build America’s next stealth fighter?

The culmination of a century’s worth of work

After languishing in obscurity for nearly a decade, Ufimtsev’s book found its way into the hands of the U.S. Air Force’s Foreign Technology Division, which published an English translation in September of 1971. That translation, unsurprisingly, quickly found its way into the hands of another legendary engineer out of Lockheed’s Skunk Works division named Denys Overholser.

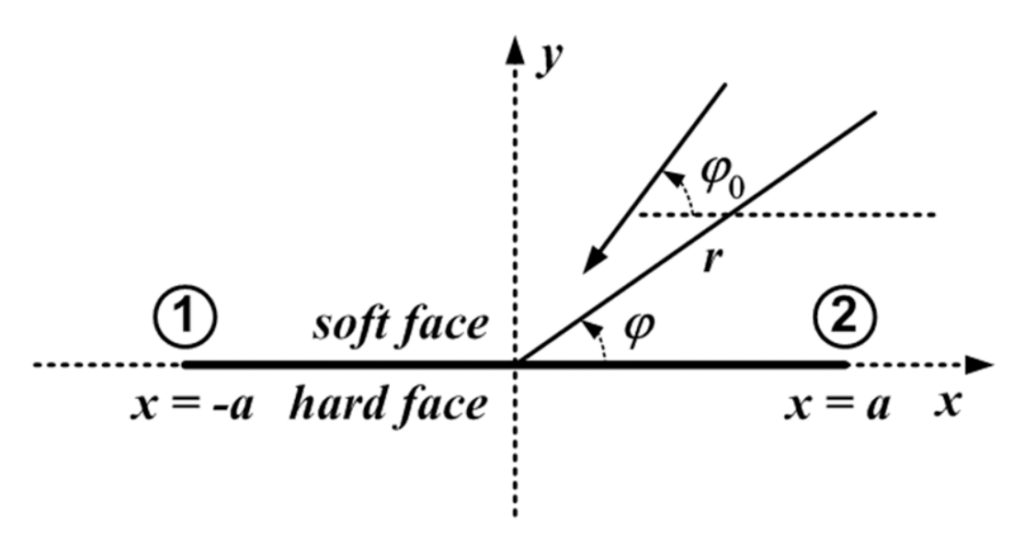

While Overholser himself described Ufimtsev’s work as, “so obtuse and impenetrable that only a nerd’s nerd would have waded through it,” he quickly recognized that a creative interpretation of the book could offer a means by which one could calculate how electromagnetic energy would reflect off of a two-dimensional shape.

Overholser then reasoned that if they could break down the design of an aircraft into a collection of two-dimensional triangles, it could be possible to calculate an aircraft’s complete radar return without having to actually build it and stick it in front of a radar array for testing like Boeing’s Quiet Bird. This would dramatically reduce both the costs and time associated with fielding capable new stealth designs.

Ufimtsev’s work was a vital piece of the puzzle, but not all of it. Overholser and mathematician Bill Schroeder also incorporated elements of the work of a 19th-century Scottish physicist named James Clerk Maxwell, who devised equations about the propagation of energy reflected off flat surfaces had informed Ufimtsev’s work as well. They also turned to the radar reflectivity studies of German engineer Arnold Johannes Sommerfeld.

Related: Here are the 12 new stealth aircraft currently heading toward service

The first stealth aircraft was also the first aircraft designed using a computer

Overholser and Schroeder slowly but surely developed a computer program that could leverage the complex equations their sources had developed over the course of the past century. It would break down an aircraft’s design into more digestible two-dimensional bites, then combine the long list of calculations into a single radar cross-section, or predicted radar return for the aircraft.

This allowed Lockheed’s engineers to bridge the essential gap between the stealthiest possible design and a shape that could actually fly in a controllable manner. The effort was painstaking, beginning with an unflyable shape dubbed the Hopeless Diamond, maturing into the Have Blue technology demonstrator, and finally… the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk.

Today, we see the Nighthawk as the beginning of stealth, but in truth, it was a culmination of efforts spread across not just the globe, but the ages.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Russian planes keep getting blown up in airfields hundreds of miles from the fighting, exposing embarrassing gaps in its defenses

- This is what it takes to become a legendary Marine Raider

- What exactly is MARSOC, the Marines’ elite special operations component?

- We asked AI to create images of top-secret new stealth aircraft and these were the results

- The history of MARSOC is the history of the Marine Raiders

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Gear & Tech

The AGM-181 LRSO missile will modernize America’s nuclear triad

Navy will soon announce the contract award for its F/A-XX 6th-generation jet, according to reports

America’s new air-to-air missile is a drone’s worst nightmare

What we can deduce about the Boeing F-47 and its capabilities so far

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page