The Air Force wants to see how good the F-22 can get

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

With the future of America’s next air superiority fighter now in question, America’s king of the skies, the F-22 Raptor, is set to extend its reign well into the 2030s, thanks to a slew of multi-billion dollar upgrades already underway – and the list keeps getting longer.

Just last week, the Air Force awarded another billion-dollar contract to RTX (formerly Raytheon) for a slew of new sensor upgrades meant to help ensure the world’s first-ever stealth fighter remains the best-ever at its air combat role.

But with America’s F-22 fleet already eclipsed in numbers by China’s 5th generation J-20s, China’s carrier-capable J-31 stealth fighter making its way toward service, and a half dozen other stealth fighter programs rapidly maturing, the question American planners have to be asking themselves right now is… Just how good can America make a stealth fighter that was largely designed in the 1980s, started flying in the 1990s, and in terms of airframe hours, is rapidly approaching middle age?

The answer, mounting evidence suggests, is scary good… But with such a small fleet of combat-ready Raptors, the next question that has to be asked is: Is scary enough?

Air Superiority in the age of ‘Goldeneye’

The F-22 Raptor’s sleek and stealthy design, incredible aerobatic performance, and unparalleled reputation gained through years of dominating air combat exercises the world over is often more than enough to make you forget that this aircraft, in its general production state, has been flying since before the founders of Google even registered that domain; when buying gas in Los Angeles cost $1.36 a gallon, and when the best video game in the world was Goldeneye: 007.

More than a quarter-century ago, the F-22 Raptor’s first flight ushered in a new era in tactical aviation, changing more about the future of air combat in a single afternoon than arguably any flight since Germany’s Me 262 introduced jet propulsion to fighter designs. This new fighter was so powerful that it produced more thrust without its afterburners engaged than the legendary F-15 Eagle could at full tilt – and when Raptor pilots decided to really lean into the throttle, the F-22’s immense power even eclipsed that of the SR-71 Blackbird. And all of that insane power was funneled through a pair of thrust-vectoring nozzles that gave the aircraft unparalleled maneuverability in America’s fighter stables.

Equipped with the most advanced and powerful radar ever affixed to a fighter at the time and new data-fusing avionics that could draw pertinent information about the battlespace from a bevy of cutting-edge sensors carried onboard (as well as from a long list of others carried by other platforms), the F-22 provided its pilots with more situational awareness than any fighter ever had before.

And in the court of public opinion, all of that even falls short of the Raptor’s true claim to fame – an unbelievably small radar return, delivered through a combination of advanced stealth design and radar absorbent materials. The F-22 is so stealthy, in fact, that despite being the oldest stealth fighter in service on the planet, it also remains the stealthiest, with a radar cross-section that’s generally estimated to be as much as 15 times smaller than the F-35, and maybe 100 times smaller than China’s J-20.

This combination of raw power, maneuverability, advanced avionics, and, of course, stealth, all coalesced in a fighter so capable it not only became the basis for the 5th generation of fighters but also arguably helped to introduce the general public to the very concept of fighter generations in the first place.

The Raptor takes the Eagle’s crown

The Raptor was so good that in 2002, three years before reaching operational service, former Eagle driver turned Raptor test pilot Mike ‘Dozer’ Shower and three of his F-22 flying peers wiped out 12 F-15Cs in less than two minutes in one of several air combat exercises that saw Eagles falling time after time to America’s newest bird of prey.

The F-15 had never lost an air-to-air engagement to an enemy aircraft, with an unmatched air combat record of 104 wins and 0 losses, but even the Eagle was all but defenseless when it came to engaging the Raptor.

“In an F-15 you’re sensor operator, you’re working the radar; you’re the guy working this all out and managing the systems and putting together the 3D picture in your head. That’s the difference with the F-22 Raptor. It does it all for you,” Shower recalled. “You could take four weapons instructors in an F-15 each and you could have some lieutenant who is ‘weapons clueless’ and he’s gonna find them all and kill them all. Then you put one really good guy in an F-15 against a Raptor and he’s still gonna get killed; there’s that much of a difference in technology.”

Even today, some 26 years since the Raptor first took flight, the F-22 remains the measuring stick by which all new fighters are compared, with only one tactical aircraft eclipsing the jet’s onboard technology (the F-35), and none capable of delivering the same combination of 21st-century stealth along with decidedly 20th-century brute force combat prowess.

But despite the Raptor’s long list of accolades, there is no denying that the F-22 also comes with a long list of downsides.

The king of the skies becomes an endangered species

The F-22’s production run, abbreviated to just 186 airframes and only 150 combat-coded jets, doomed the Raptor to incredibly high per-unit costs, similarly high maintenance costs, and worst of all, ensured no F-22 could be replaced if damaged, shot down, or simply aged out of service. To put it simply, the Raptor may be the deadliest jet in the sky… But ever since the sun set on its production line, it’s also been an endangered species.

In fact, were it not for the F-22’s early cancellation, it’s all but certain that the Next Generation Air Dominance program, meant to field a replacement for the Raptor itself, likely wouldn’t have materialized until much later, with F-22’s seeing consistent improvements throughout the rest of the intended production run resulting in more modern, and more capable, Raptors entering service years later than the final F-22 was delivered.

But now, as the Air Force’s budget modeling begins to buckle under the weight of cost overruns associated with strategically necessary programs like the LGM-35A Sentinel ICBM, replacing the Raptor may have to be pushed out by years – and that means the fighter that once proved to the world that it could take on four F-15s and win is now facing a potential future where numbers alone will force it to take on just as many 5th generation J-20s in order to survive.

Because with Raptor production permanently halted and NGAD production being pushed further back by the day, it’s no longer a question of which is better, the F-22 or China’s J-20… And instead, it’s rapidly becoming a question of just how many mass-produced J-20s can each Raptor really take on.

To that end, the United States Air Force has committed to spending billions to upgrade its small fleet of F-22s, addressing longstanding shortcomings in the platform and fielding a slew of entirely new capabilities.

But for a jet that can trace its earliest design lineage all the way back to the 1970s, and that was designed for the relatively short-range engagements of a Cold War turned hot over Europe, upgrading the F-22 Raptor for a potential conflict over the Pacific is no small undertaking.

Fixing the Raptor’s flaws

The first shortcoming the Raptor will need to overcome for Pacific operations is range. With roughly 18,000 pounds of fuel onboard and a combat radius of between 470 and 600 miles (depending on supercruising (or flying at supersonic speeds without the use of afterburners), F-22s meant to engage Chinese fighters in the air superiority mission would have few basing options in theater. Installations like Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, only around 400 miles from China’s coast, would be the target of massive cruise and ballistic missile strikes, potentially cratering runways and destroying aircraft on the tarmac and in hangars. This could force F-22s to fly combat sorties from significantly further out, which would reduce the total number of combat sorties flown while dramatically increasing logistical support needs from other platforms like refueling tankers.

To address this range issue today, Raptors often fly with a pair of 600-gallon non-stealth fuel tanks mounted on underwing pylons, each of which provides an additional 4,000 pounds of fuel for a combined total of some 26,000 pounds. The F-22’s pair of powerful F119 afterburning turbofan engines rip through between 30 and 38 pounds of fuel per mile, so these droppable-fuel tanks stretch the Raptor’s legs out to nearly 1,840 miles (one way), or a combat radius of better than 900 miles (in the best of circumstances).

But as I mentioned before, these fuel tanks were not designed for stealth applications, and as such, compromise the F-22’s best-in-class stealth profile. And even if the tanks are dropped (as pilots would do if they found themselves in a fight), the mounting hardware for the pylon and detached plumbing for the fuel would remain, which also has a negative effect on stealth. As such, today, Raptors have to choose between range and low-observability – a trade-off that could be critical over the Pacific.

And that’s where the Low Drag Tank and Pylon program comes in. This effort aims to not only field stealthy underwing fuel tanks that don’t have nearly the same negative effect on the Raptor’s radar return, but that also break away clean, eliminating leftover hardware that could make the F-22 easier to detect – after dropping its stealthy fuel tanks.

The next most pressing shortcomings the F-22 faces in the 21st century are its lack of infrared search and track and helmet-cued targeting capabilities. The first is a passive means of targeting that detects and tracks the heat signature produced by enemy fighters, which can allow you to target even stealth aircraft that don’t appear on radar. This capability was envisioned as standard on all Raptors initially, but was ultimately cut from the program as a cost-saving measure. In the years since, IRST capabilities have become not just far more common, but increasingly necessary as stealth itself becomes more ubiquitous around the world.

Giving the Raptor new (infrared) eyes

Integrating that IRST sensor into the airframe itself would be an immensely expensive endeavor, and it seems the Air Force has gotten around this issue by instead adding stealthy underwing pods that are mounted outboard of the stealthy fuel tanks. Like the fuel tanks, these sensor pods will have a negative impact on the aircraft’s overall stealth profile, though that impact is clearly mitigated via a radar-deflecting design and radar-absorbent coatings.

Infrared Search and Track targeting capabilities have been around for a long time. In fact, the F-14 Tomcat started flying with an IRST pod mounted under its chin in 1991. Today’s IRST systems, however, are far more advanced and capable. Specifics regarding the latest and greatest IRST targeting systems are obviously limited, but it is worth noting that the F-22 program office specified in this program’s request for submissions that the Raptor’s new pod “provide long-range infrared sensing and object detection capabilities.”

“Long range” is not a term with clearly defined parameters for this application, but there are some metrics we can look to in order to assess how promising the Raptor’s new targeting chops will be. First and foremost, a long-range sensor would almost certainly mean an ISRT system capable of spotting even stealthy threats from beyond visual range, which is generally considered to be 20 nautical miles out (roughly 23 miles).

The Eurofighter Typhoon’s PIRATE IRST system was touted as being capable of detecting subsonic fighters at ranges of 50 kilometers (31 miles) from head-on and 90 kilometers (56 miles) with a clear view of their engines all the way back in 2008. The Russian Air Force claims similar ranges for their OLS-35 system found in aircraft like the Su-35.

Unsurprisingly, claims out of China are significantly greater, but come with the standard lack of evidence to assess. Wang Yanyong, technical director for Beijing A-Star Science and Technology, went on record in 2021 to claim that the EOTS-89 electro-optical targeting system (EOTS) and the EORD-31 infrared search and track (IRST) system in development for China’s J-20 were capable of targeting the B-2 Spirit from behind at ranges of 150 kilometers (93 miles) and the F-22 at 110 kilometers (68 miles).

It’s important to remember that IRST systems don’t function like radar, for better and worse. They’re considered passive sensors, meaning they don’t broadcast any energy to be detected by adversary fighters, but they’re also limited by atmospheric conditions and a litany of other environmental factors.

While we tend to talk about IRST systems individually to highlight the implications of their use, the real value is found through integrating IRST systems with radar and other onboard sensors to create a more robust targeting image of the battlefield – using different forms of detection and targeting to offset adversary countermeasures and improve the likelihood of a successful engagement.

Unlocking the full capabilities of weapons like the AIM-9X

And while on the topic of targeting, the F-22’s lack of helmet-cued targeting is perhaps its most glaring shortcoming on the modern stage. Today, the Raptor is the only front-line fighter in the American arsenal that lacks this ability, forcing F-22 pilots to actually orient the nose of their aircraft at their opponent to lock on and fire. Of course, thanks to the Raptor’s insanely powerful AN/APG-77V1 active electronically scanned array radar and its stealth, this can usually be done from 60+ miles away without the adversary fighter even being aware of the F-22’s presence, but it nonetheless represents a shortcoming in the fighter’s pilot interface.

While little is known about the helmet-cued targeting capabilities believed to be making their way toward service in the F-22, we know the Air Force was testing a modified version of the Thales Scorpion HMD in the Raptor as far back as 2014, and while there has historically been clearance issues with the Raptor’s uniquely shaped canopy, it seems like an engineering nut the Air Force would be eager to crack, and indeed, they may have with the Next Generation Fixed Wing Helmet program that saw testing in the Raptor last year.

The addition of helmet-cued targeting would allow the Raptor to take full advantage of modern weapons like the AIM-9X, which is famously so maneuverable that it can engage adversaries flying behind the launching aircraft, but until F-22 pilots can target these aircraft using their line of sight, this high-off-boresight targeting capability remains untapped in the Raptor.

The addition of IRST, helmet-cued targeting, and stealthy fuel tanks alone will represent a massive leap forward in F-22 capabilities, but these are really just the most conspicuous changes to the Raptor. Much of the rest of the ongoing multi-billion dollar upgrade lies beneath the fighter’s radar-absorbent skin, including new encrypted communications systems and a bevy of other new sensors being integrated into the F-22 as a bridge toward the NGAD fighter slated to replace it.

Bringing the F-22 into the 21st century

One of the more secretive additions to the F-22 is the introduction of the new Government Reference Architecture Compute Environment, or “GRACE.” This open-system software architecture will improve processing power, pilot interface capabilities, and even allow the aircraft to adopt software that wasn’t originally designed for the Raptor.

Another new system being bolted onto the Raptor is the Northrop Grumman-led Embedded Global Positioning System (GPS) / Inertial Navigation System (INS) Modernization, also known as the LN-351 EGI-M. This advanced navigation system takes advantage of the Air Force’s newest and most modern GPS III satellites which can transmit directly to the aircraft via high-gain directional antennae that are encrypted and extremely difficult to jam or spoof. This, in conjunction with an updated inertial guidance system that can function with high degrees of accuracy with only intermittent or limited access to GPS signals will allow F-22s to operate freely in GPS-denied environments.

Other new systems include the Mode 5 Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) transponder, which is rapidly becoming standard across NATO air forces. This military-specific identification system uses allows for what the Pentagon describes as a secure and encrypted data exchange through use of the new waveform, making it easier than ever to discern between friendly and enemy aircraft at a distance. The Mode 5 IFF integrates seamlessly with surface-based air defense systems like Patriot and AEGIS, and as a “lethal interrogation format” transponder, can even receive responses from friendly transponders that are set to “standby,” further limiting the chances of friendly fire in beyond-visual-range engagements.

There has even been mention of upgraded avionics making it possible for F-22s to fly alongside AI-enabled drone wingmen, just like the forthcoming Block 4 F-35 and Next Generation Air Dominance Fighter. This alone could have a massive impact on the F-22’s combat capacity, further bridging the gap between the oldest 5th generation fighter in the world and the forthcoming 6th generation of jets.

Other upgrades to the aircraft’s operational flight program, electronic warfare capabilities, and communication systems have also been listed in Air Force budget documents, but details regarding their improvements remain few and far between. Overall, the F-22 fleet is expected to receive roughly $7.9 billion in upgrades by 2029, and by October 31, 2031, that figure is slated to reach just under $10.9 billion.

To put that figure into context, the F-22 upgrade budget is enough to purchase 132 new F-35As and still have enough left over for a very comfortable retirement. In terms of the 150 combat-coded F-22s in America’s stable, that shakes out to roughly $72.6 million in upgrades allocated to each individual Raptor.

In the future, the F-22 Raptor won’t be fighting alone

The F-22 Raptor was designed for an 8,000 flight-hour lifespan, and with no means of replacing airframes as they age out of service – that’s effectively it, barring an even pricier service life extension program. However, in 2022, it was reported that the most heavily used Raptors in the American stable had yet to reach the 4,000-hour mark, and with peacetime operations usually accruing only 250 or so flight hours per year, it isn’t unreasonable to say F-22s could keep flying for decades to come.

But the question remains, even with lots of hours left on the airframes and billions of dollars poured into upgrades, are America’s 150 F-22 Raptors enough to take on hundreds of Chinese J-20s and J-31s as they continue to pour out Beijing’s production lines? The objective answer is… likely not.

But then, could those 150 upgraded F-22s, accompanied by 300 more AI-enabled collaborative combat drones, backed up by hundreds of Tier 3 or Block 4 upgraded F-35s, all carrying next-generation air-to-air weapons like the AIM-260? The answer there is… almost certainly.

And that’s before we consider the potential air-to-air capabilities of the B-21 Raider, Super Hornets flying a hundred miles back armed with the new extremely long-range AIM-174s, thousands of battle-proven 4th generation fighters equipped with advanced electronic warfare capabilities, new air-launched decoys and jammers, and an ever-growing list of allies operating F-35s of their own.

To put it simply, fielding 200 new NGAD fighters would offer the United States the most direct and potent solution for air supremacy in the decades ahead, and it seems likely that this effort will ultimately see production in one form or another. But it’s the responsibility of the US Defense apparatus to plan for the possibility that America may not see another high-end fighter emerge for years to come.

And if that is the case, the F-22 Raptor may not be the best fighter America has the means to build in the 21st century… But without a doubt, it will still be the best fighter any nation has in the sky.

And that just might be enough.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- These are the pistols that America’s generals carry

- The Intelligence Support Activity – one of America’s most secretive special operations units

- The ACR program or how the Army spent 300 million dollars on nothing

- Video: The Air Force wants to push the F-22 further

- What actually happens when fighter pilots take off their masks?

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower

How an F-15E scored its only air-to-air kill… with a bomb

The military roots of Juneteenth and why we celebrate it

BUD/S instructors have their favorite games to make SEAL candidates suffer

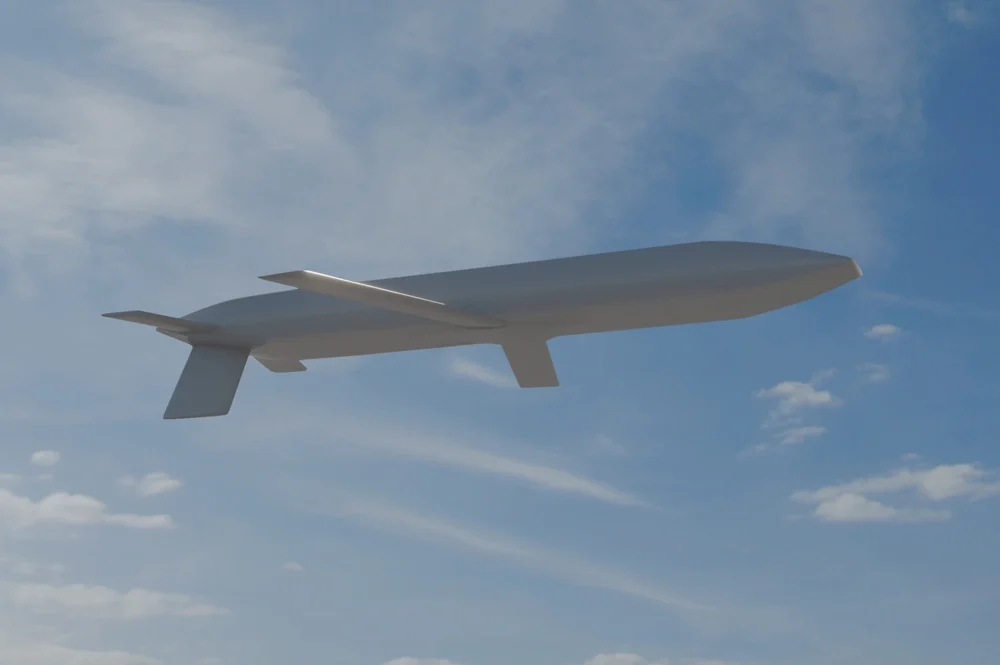

Air Force gives us a glimpse of its new AGM-181 LRSO nuclear missile

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page