The Air Force created a F-35 ‘Frankenbird’ for the first time – with help from the A-10

- By Hope Seck

Share This Article

When the landing gear of an Air Force F-35 collapsed after the fighter landed at Hill Air Force Base, Utah, in June 2020, it appeared the nearly $100 million plane had reached the end of its road. But the F-35 is now set to fly again five years after its faceplant, thanks to the donation of a new nose from another unlucky aircraft.

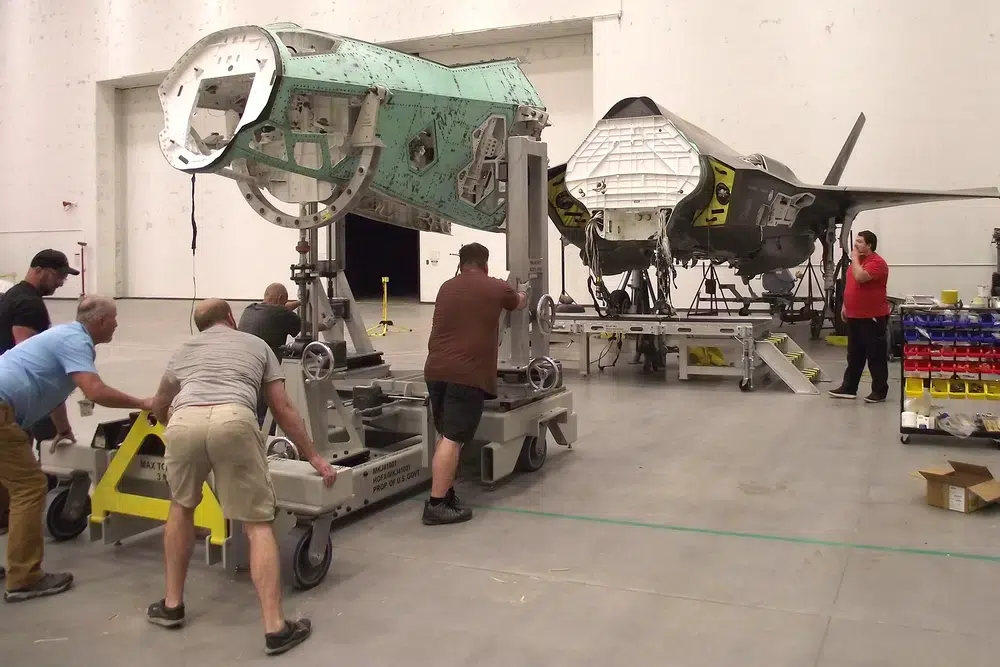

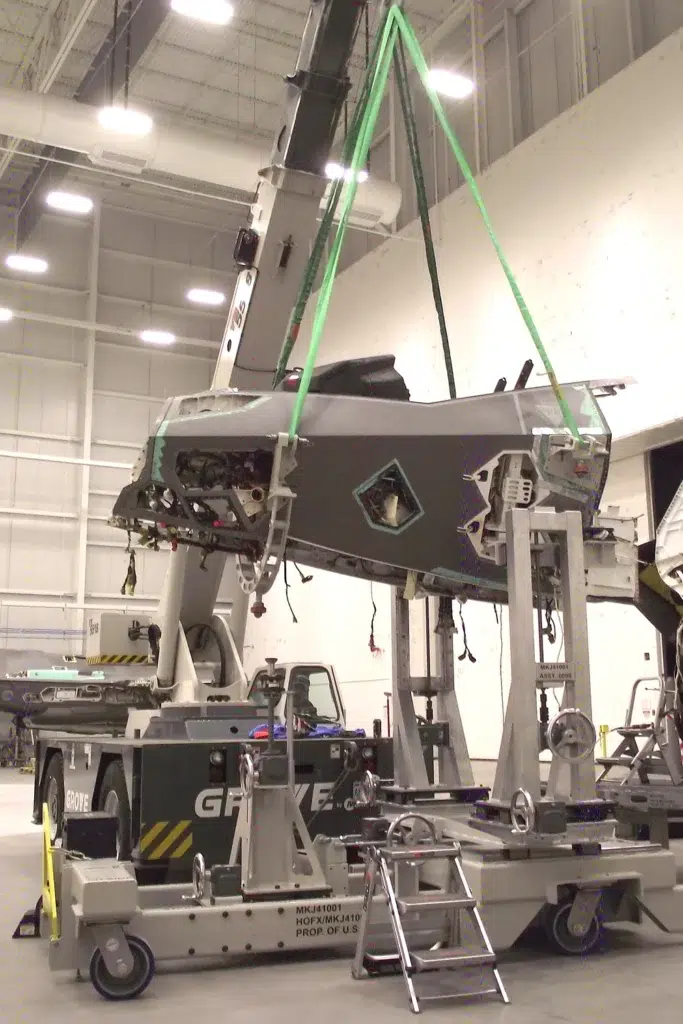

In what engineers are calling a first-of-its-kind project for the F-35, the two aircraft halves are being stitched together to create one “Frankenbird” – with help from tools developed for the Air Force’s beloved A-10 Thunderbolt.

Even before the F-35 belonging to Hill’s 388th Fighter Wing had its catastrophic 2020 runway landing, Joint Strike Fighter program officials had been looking for an opportunity to demonstrate a major repair, said Dan Santos, heavy maintenance manager for the F-35 Joint Program Office. Santos had previously worked on the A-10 and F-16 Fighting Falcon and had supervised repairs that involved “splicing” sections of different aircraft to create one new working plane.

“We saw this as an opportunity to pave the way for the future,” Santos told Sandboxx News. “Accidents do happen. And so we just have to be prepared, to be able to repair the aircraft and provide them to the warfighter as soon as possible.”

As it happened, a replacement nose section was already available via an aircraft that had long been consigned to the scrap heap. In July 2014 another Air Force F-35 had been severely damaged when fire spread from an engine just ahead of takeoff for a training mission from Florida’s Eglin Air Force base. The incident prompted a total grounding of F-35s; an investigation would later reveal the cause of the fire to be an engine flaw. Since that fire, the F-35 had been doing hard-luck duty as an air battle damage and repair trainer, subjected to various simulated mishaps so Air Force maintainers could learn how to fix them.

Without the nose from this retired trainer, “we would have probably been waiting for a while to get a production section built,” Santos said.

Related: F-35 versus A-10 showdown revived as new documents come to light

Even with experience doing major surgery on legacy aircraft, work on the F-35 presented unique challenges, Santos said. Its stealthy profile required a greater level of precision in aligning components, he explained, and the F-35’s more uniform construction also made the work of stitching pieces together more difficult. For example, he said, the trunnion, a component that connects the landing gear and main airframe, is simple to remove and replace on legacy aircraft. By contrast, that part is built into the body of the F-35, meaning replacing the part is more complex and requires more in-depth structural work.

By contrast, “A-10 is a subsonic-caliber airplane, and so taking the A-10 apart and putting it back together, it’s like a Tonka toy,” Santos told Sandboxx News referring to the popular toy trunk.

Though A-10 Frankenbird fixes might not require the same labor and precision as the F-35 does, Santos did say that work on the Thunderbolt provided a roadmap for the first-of-its-kind F-35 repair.

“That airplane was designed to go into the fight and be down and dirty and probably get damaged,” Santos said of the A-10. “Hence the reason for the titanium tub around the pilot.”

Because in-depth repairs were so common on the A-10, he said, the Air Force built a special fixture that allowed maintainers to separate the aircraft into four sections and hold them stable. That inspired the F-35 repair team, consisting of engineers from the Joint Program Office and manufacturer Lockheed Martin Corp. They built a modular fixture specific to the F-35 that would not only support the current repair, but also be transportable around the world for future repairs. And, Santos said, it worked like a charm.

Related: This is why the Air Force is naming its highly modernized new bomber the B-52J

“We did a nose stitch on the F-35, and it came right off, so easily. And then the new one slid right on,” Santos told Sandboxx News. “Even Lockheed was impressed with themselves on the fixture.”

While there are no more current F-35 candidates for Frankenbird-style repairs, Santos said the work done on the current aircraft will inform future efforts – and added that the common design of the F-35 means that someday different variants – a Marine Corps F-35B and a Navy F-35C, for example, might also be stitched together to form a truly joint hybrid.

“If they’re interchangeable, you bet,” he said.

The current repair project is three months ahead of schedule, Santos said, meaning the repaired mishap aircraft, currently designated AF-211, is expected to get power in early 2024 and be flightline-ready by 2025.

“We’re working as quick as we can to get it done as soon as possible,” he said.

And although the F-35 nose donor is getting the worse end of the bargain in the repair, it will still be able to continue as a battle damage trainer, according to Santos. It will get the beat-up nose from the plane being repaired to fly again, which maintainers can then work into a serviceable, though not flight-worthy, shape.

“In essence, they’re going to get the airplane [that was damaged in 2014] back and be able to use it for training,” Santos said, “And then we’ll be able to repair the mishap aircraft [that was damaged in 2022] and put it back into the fight.”

Read more from Sandboxx News

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Hope Seck

Hope Hodge Seck is an award-winning investigative and enterprise reporter who has been covering military issues since 2009. She is the former managing editor for Military.com.

Related to: Airpower

Dogfighting in space? Not too far-fetched, Space Force chief says

New master’s degree will train Top Gun pilots on foreign adversaries and space warfare

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page