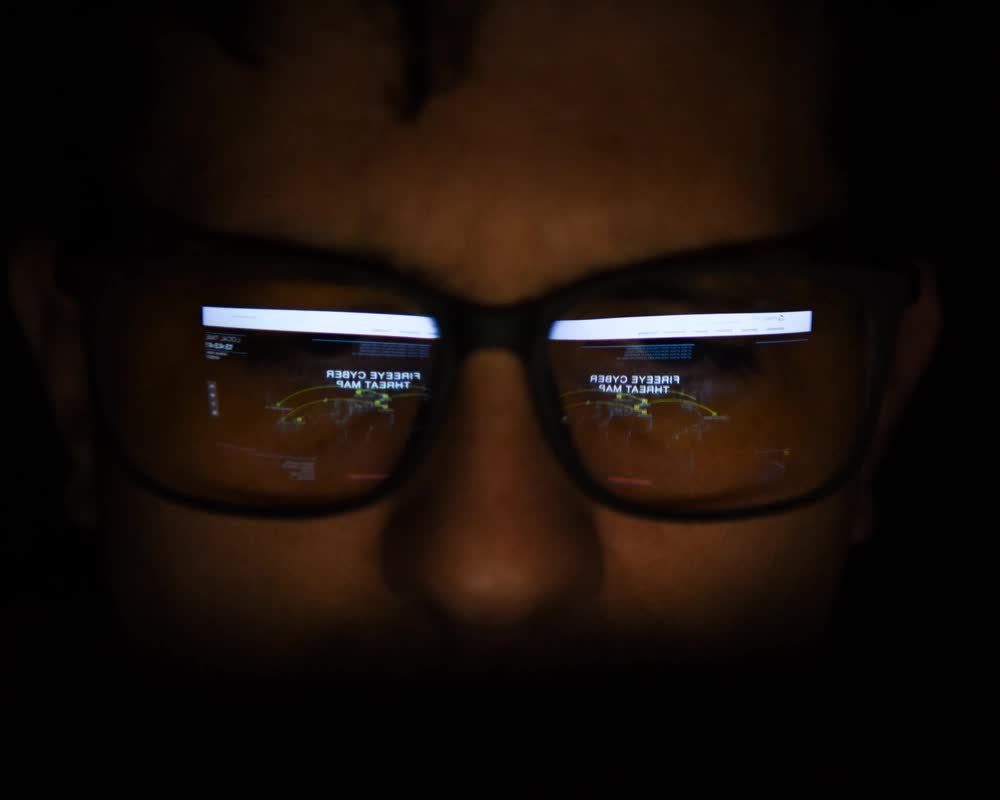

Stuxnet unleashed: The tactics behind the world’s first cyberweapon

- By Stavros Atlamazoglou

Share This Article

By the end of the 2000s, tensions in the Middle East were growing. The United States was bogged down in a bloody two-front war in Iraq and Afghanistan, meanwhile, Iran was pressing on with its nuclear weapons program. A theocracy fanatically opposed to the U.S., Iran was threatening to create a nuclear weapon and use it against U.S. interests and allies in the area.

Then in 2010, seemingly all of a sudden, the Iranian nuclear program started falling apart and Iranian scientists leading the country’s covert nuclear program witnessed in dismay more than 1,000 centrifuges spinning to their destruction without any apparent reason. But there was plenty of reason, and it had a name: Stuxnet.

Stuxnet, as analysts came to name the malware, was developed by an unknown party – though it was most likely the U.S. and Israel. Up until then, a successful computer network attack with large physical effects belonged to the sphere of speculation. No one had done it, and many doubted if anyone could pull it off. The goal of the attack was to delay Tehran’s path to a nuclear weapon and give diplomacy a chance. The most complex cyberattack to date, Stuxnet infected the Iranian systems over several years, most likely starting in 2007. The attackers deployed several versions of the malware against the Iranian nuclear facilities at Natanz. Two versions, one dating from 2007 and the other from 2009, stand out. Interestingly, there was a significant change of tactics between these two versions of the same malware in the middle of the operation.

In a previous installment of Stuxnet, we covered Operation Olympic Games and the international backdrop in which it took place. In this article, we will explore the tactical aspect of the pioneering malware and its effect on the Iranian nuclear program.

Section I: Operation Olympic Games

Derailing the covert nuclear weapons program of one of your archenemies requires guts and technical expertise few countries in the world have. Understanding the monumental challenges inherent in such an operation is perhaps why the entities behind Stuxnet codenamed the cyberattack Operation Olympic Games – or perhaps it was because several nations were reportedly involved in the operation, including the United States, Israel, Germany, France, and the Netherlands.

Operation Olympic Games, primarily a U.S.-Israeli operation, infected the Iranian systems at the Natanz nuclear facility with Stuxnet sometime in 2007. One year earlier, negotiations between Iran and the U.S. and the European Union had failed. As a result, Tehran resumed its uranium enrichment process at the Natanz facility installing the first batches of centrifuges necessary to enrich uranium and produce weapons-grade material for a nuclear warhead.

Everything began with a beacon. The attackers created a beacon that could collect information on and map out the networks of the Natanz nuclear facility. Then, a witting or unwitting human source carried the beacon into the facility. The attackers could now design and test Stuxnet based on the exact conditions it would operate in.

The cyberattack came in waves. The attackers delivered the first payload between 2007 and 2008. The first version of the malware spread via USB drives. Reports indicate that the Dutch foreign intelligence agency AIVD, which was working closely with the CIA and Israeli Mossad, had managed to recruit an Iranian engineer with access to the Natanz nuclear facility. His handlers gave him a corrupted USB flash drive that first put Stuxnet into the Iranian systems. The agent then visited the Natanz nuclear facility several times, allowing the attackers to tailor their approach better. Using an agent highlights that cyber is just another intelligence and warfare domain and works best when used in conjunction with other disciplines. Subsequent versions of Stuxnet could spread from and to computers and networks within the facility without physical access; in total, the malware used no less than eight propagation methods. The attackers clearly wanted to ensure that Stuxnet crossed the air gap in place for security and to reach the precious centrifuges.

Related: What is signals intelligence and who is charged with providing it?

Once in place, Stuxnet exploited several zero-day vulnerabilities (which are known security holes that haven’t been patched) in the Iranian machines’ Windows operating systems to gain elevated privileges and execute its payload. In total, it exploited at least six zero-day vulnerabilities, four of which were in the operating system.

Stuxnet installed itself as a rootkit to make it harder to detect and allow backdoor functionality. The attackers also used stolen valid digital certificates from Realtek, a Taiwanese semiconductor company, to make Stuxnet’s components look legitimate. To remain undetected and evade security scans, the malware used several advanced techniques, including code obfuscation and anti-virtual machine techniques. Then, Stuxnet started spreading to other machines and networks by exploiting Windows vulnerabilities.

The attackers sought persistent engagement and used several methods to communicate with the malware, including encrypted communication channels and domain generation algorithms. The more a malware stays on target, the higher the danger of discovery by network defenders. However, despite the extremely high stakes behind the operation, it seems that the attackers were highly confident in their tradecraft and Stuxnet’s capabilities to take the risk of maintaining persistent engagement.

When it came to command and control, Stuxnet was again ahead of its time. The cyberweapon could not just report back to the command and control server about its progress in the Iranian computers and networks: it could also download upgrades to the malware. When a new version of the malware infected a machine that had already been compromised, the two versions worked together, updating older versions and communicating back to the operators. Through this constant communication, the attackers had a good understanding of which machines and networks had been infected.

Although there were several different variants of the malware over the years, two are the most significant, the 2007 and 2009 versions.

Related: What exactly is Iran’s shadowy Quds Force?

The 2007 version of Stuxnet exploited vulnerabilities in SIEMENS Step7 software and SIEMENS WinCC SCADA systems that the Iranians used in their industrial control systems to control the precious centrifuges. The malware then started to manipulate the programmable logic controllers in the industrial control systems, increasing gas pressure that flowed out of the centrifuges and malfunctioning the process. These industrial control systems managed and controlled the centrifuges necessary for the program. A device that separates isotopes of uranium by spinning at high speeds, a centrifuge can produce both enriched uranium for nuclear power and weapons production. The Iranian scientists had no clue that what seemed like random accidents or bad science was the result of a cyberattack.

In 2009, however, the attackers changed tactics. The new version of the malware targeted the rotors at the core of each centrifuge and manipulated their speed. The attackers made the centrifuges spin at extremely high and low speeds, causing a catastrophe inside the covert nuclear facility. However, the Iranian scientists still did not understand that they were under attack. The Iranians thought that they had placed significant cyber and physical safeguards and defenses around the Natanz nuclear facility to ensure that nothing, including a computer network attack, could derail their nuclear weapon ambitions. However, the 2009 version of the malware was more aggressive and spread beyond Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility.

Crucially, Stuxnet was the cyber version of a precision-guided missile – it was only meant to unleash its payload if it found the right network conditions and equipment. If the malware did not find the right conditions, it remained dormant. Moreover, there was a built-in self-destruction mechanism that would make the malware kill itself after June 24, 2012.

In the summer of 2010, VirusBlokAda, a rather obscure Belarussian antivirus company, was the first to discover the existence of Stuxnet. They did so when they examined a machine from Iran that the malware had infected. The Eastern European company quickly alerted other cybersecurity analysts, thus spreading the news of Stuxnet.

At the end of the day, when the dust settled, Stuxnet had managed to destroy approximately 1,000 centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear facility. In a single stroke, Iran had lost about 20 percent of its uranium-enriching capability, taking Tehran’s nuclear weapons program years back.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The F-35 hits more milestones but a software issue threatens the jet’s upcoming upgrade

- Why a principal designer of the B-2 stealth bomber is in a supermax prison

- How can the US Navy boost its suffering recruitment?

- Deadliest Warrior: A campy, absurd, but so much fun show

- The Army is stepping into the future with these three vehicles

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Stavros Atlamazoglou

Greek Army veteran (National service with 575th Marines Battalion and Army HQ). Johns Hopkins University. You will usually find him on the top of a mountain admiring the view and wondering how he got there.

Related to: Gear & Tech, Military Affairs

Boeing has managed to win the contract for America’s NGAD fighter

Could France undertake the role of Europe’s nuclear protector? Potentially

What are the differences between the six generations of fighter aircraft?

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page