Still in Saigon – How a Vietnam War song can speak to all veterans

- By Travis Pike

Share This Article

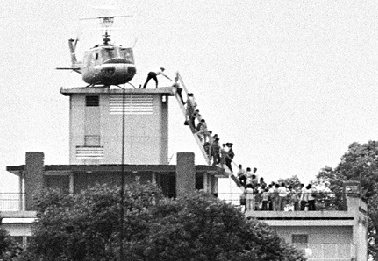

Music can often be universal, and veterans are clearly not the only people who suffer from trauma. The song Still in Saigon came out in the 80s when songs about Vietnam were popular. Bruce Springsteen had Born in the U.S.A., Huey Lewis and the News had Walking on a Thin Line, and Charlie Daniels had Still in Saigon which is the only one I really relate to.

Dan Daley has stated that the song is a metaphor for other kinds of traumatic experiences.

Still in Saigon – A Personal History

Charlie Daniels was not a veteran and neither was Still in Saigon’s songwriter Dan Daley. How the two men captured the feeling of a returning veteran is a testament to their skill. Daniels famously wrote his own music, rarely taking a song from an outside writer. Yet, he must have seen the potential of the song when he decided to sing it.

I first heard the song from my dad, who was a big fan of Charlie Daniels (I’ve heard Devil Went Down to Georgia about eight million times.)

I remember, as a kid asking my dad what the song was about. I got a brief explanation that Saigon was in Vietnam, and it was about the Vietnam War. When I pressed on about its meaning, I got a rather simple explanation. “Oh, he’s just having flashbacks to the war.”

I accepted this as a kid and never really thought about the song again until recently. I played for my kids Devil Went Down to Georgia, and they enjoyed it. After that, Youtube suggested Charlie Daniels non-stop for weeks. I saw Still in Saigon, vaguely remembered it, and hit play. Almost 30 years since I first heard the song, and a lifetime of experience has shown a new light on Still in Saigon.

Related: Guardian Encore gives veterans a chance to open up through music

Why It Works So Well Even Today

As an Afghan veteran that watched the country fall to the Taliban last year, I can’t help but relate to my Vietnam vet comrades. However, that’s not exactly why the song hits so well. Still in Saigon captures the feeling of coming home from war and being home from war. Coming home is often seen as a joyous occasion, and at the moment, it might be.

However, the fact remains that service members who commit suicide aren’t doing it while deployed but after they get home. Maybe the feeling isn’t as universal for everyone, and deployment experiences are all different. Not to pick on anyone, but the Marines in Leatherneck in late 2009 had A/C, a Pizza Hut, and Green Bean, and the Marines in Helmand slept in holes and dug up IEDs.

To me, the song isn’t just him having flashbacks, it’s him feeling like he never came home, not all the way. Part of his mind, and maybe his soul, if you believe in such a thing, is still in Vietnam. I’ve never told anyone this, so it’s odd I’m typing it for you now, but I feel the same way.

I feel like part of me is still in Helmand province and part of Afghanistan is still with me. I can’t shake it. It’s something I think about every day.

Related: How a Green Beret achieved immortality during one of the fiercest battles of the Vietnam War

Coming Home

Still in Saigon portrays coming home as hard, and the song rightly addresses it. If you take the song at face value, it’s just two people with different opinions of our protagonist. The lyrics go:

My younger brother calls me a killer and My daddy calls me a vet.

It’s not uncommon to be treated differently and for the people you love to have a different view of you after the war. For better or worse, the phrase you can’t go home is true. You’re a different person, and their perception of you will be different.

Related: Christmas truce during the Vietnam War

More Than a Feeling

There are plenty of lines I feel represent my experience. One says,

Damned if I know who I am. There was only one place I was sure

When I was

Still in Saigon

Many veterans feel the same. Regular life back home is hard. This may sound odd, after all, how can living in such a prosperous nation be hard? A lot of it comes with expectations of society. You have a job, a wife, kids, parents, friends, school, and who knows what else, and you have to balance that with taking care of yourself.

When I left the service, I struggled with a feeling of melancholy that what I was doing after the service was useless and dumb.

Selling mattresses was a silly pursuit. In Afghanistan, my life was simple and had a purpose. I had a mission that was essentially in stone. I was a machine gunner in team 1. That’s all I was. I didn’t have many societal expectations, and life wasn’t complicated.

At the same time, I knew I was important. My machine gun laid down fire, suppressed the enemy, and allowed my squad to move under fire. I kept my head down, and if I didn’t do my job, the entire squad would fail. Every one of us in that squad had an important job, and it was necessary for our survival.

I knew who I was in Afghanistan, and it took years for me to figure out who I was when I got back home.

Related: We swore a blood oath: Former CIA officer reflects on al-Zawahiri killing

Flashbacks

The simplistic explanation that Still in Saigon was about having flashbacks should be corrected. The concept of a flashback has essentially been made into this odd hallucination veterans may experience when returning from war. In reality, anyone who has PTSD can have a “flashback” and a flashback isn’t a hallucination of a traumatic event.

It’s a moment where you are reminded instantly of an event occurring, and your body experiences the same physiological response it did during the event. They aren’t a five-minute hallucination of past events. Our protagonist isn’t having the type of flashbacks the media portrays and what they unfairly portrayed Vietnam veterans as suffering from.

The song rightly portrays that these memories can be triggered easily, regardless of where you are and what is happening. They occur to me. Anytime I smell marijuana, for example, I am taken back to Afghanistan with the mind of 19-year-old Travis. (I do miss 19-year-old Travis’ knees.)

These feelings and experiences and memories are what make up the core message of Still in Saigon. He can’t leave, and he doesn’t ever seem to voice an opinion saying he wants to leave. For many veterans, the service and war were part of our formative years. It’s who we are, and that’s why we can’t leave Saigon, Baghdad, Garmsir, Midway, or Fallujah, or wherever else your boots gathered dirt.

Read more from Sandboxx News

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Travis Pike

Travis Pike is a former Marine Machine gunner who served with 2nd Bn 2nd Marines for 5 years. He deployed in 2009 to Afghanistan and again in 2011 with the 22nd MEU(SOC) during a record-setting 11 months at sea. He’s trained with the Romanian Army, the Spanish Marines, the Emirate Marines, and the Afghan National Army. He serves as an NRA certified pistol instructor and teaches concealed carry classes.

The Switchblade, loitering munitions, and the new terrifying face of warfare

5 ways to prepare and survive the Marine Corps boot camp

Barrett’s Squad Support Rifle System will make infantry squad deadlier

The unique world and uses of howitzers

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page