SPECIAL OPERATIONS COMMAND GETS NEW HIGH TECH RADIOS

- By Stavros Atlamazoglou

Share This Article

The U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) awarded L3 Harris Technologies a $82 million contract for advanced radios.

Soon, American commandos will be fielding the Falcon IV AN/PRC-167 multi-channel manpack radio.

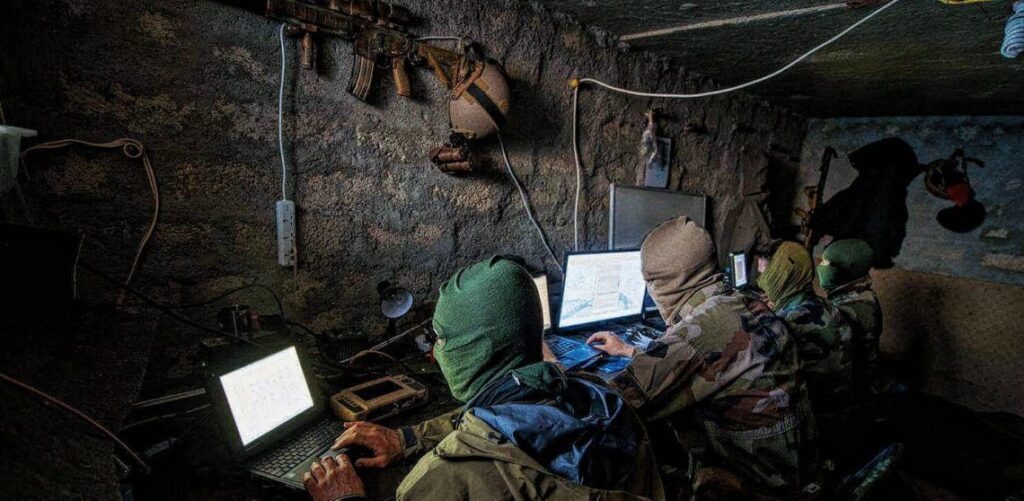

Essentially, the AN/PRC-167 brings together numerous tactical communications functions in one portable device. It also contains an LCD screen from which special operators can watch intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) footage. An added benefit of the AN/PRC-167 is that it can work with the radios of partner forces, thus increasing the interoperability of US commandos who often work with allied or partner elements downrange.

According to L3 Harris Technologies, “The AN/PRC-167 is engineered to meet multi-domain challenges of dismounted, vehicular, maritime, and airborne missions. It simultaneously runs a broad portfolio of line of sight, networking, SATCOM and resilient waveforms on each of the two 30-2600 MHz primary channels. Multiple robust mobile ad hoc networking (MANET) waveforms empower Hyper Enabled Operators with information and data analytics at the tactical edge. The software-defined manpack supports fast, in-field software updates to add resilient waveforms and new capabilities.â€

Radios are important to any unit but crucial to a special operations element. Due to their small number and habit of operating in non- or semi-permissive areas, special operations units rely on good communications with the rear to survive.

For example, Green Beret recon teams from the secretive Studies and Observations Group (SOG) that operated across the fence in Laos and Cambodia during the Vietnam War, wouldn’t have been able to fight – or indeed survive – without the close air support and extraction from air assets. And the radio was their main way of communicating with those assets.

The history of tactical military communications is fascinating.

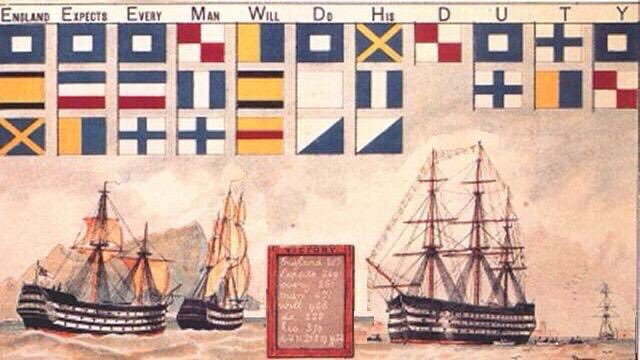

Back in the Age of Sail, ships used to communicate by signals; flags, flares, and lamps all had a use. Aboard every warship, there was a signal midshipman, usually a boy or teenager, whose job was to interpret what other ships said with the help of a signal book. The practice wasn’t very reliable and offered rife opportunities for intentional or unintentional miscommunication – there are numerous known instances where captains chose to ignore or ‘misunderstand’ the signal of an admiral before or during a battle.

Militaries began to use radio communication in earnest during the First World War. But that early technology was bulky, unreliable, and ineffective. For example, radio transmissions could be affected by the weather, and messages could only be sent to relatively small distances (2,000 yards was considered cutting-edge).

These shortcomings of radio communication meant that armies had to continue to rely heavily on phone and telegraph. An exception to the above was naval radio communication. The U.S. Navy’s radio stations could transmit far more powerful messages than those of the smaller radios used in the frontlines, and so radio was a viable method of communication at sea. Indeed, the U.S. Navy announced the First World War Armistice to its ships via a radio message.

Technological leaps during the interwar period meant that radio technology was not only viable but preferred during the next war. During the Second World War, most fighting vehicles, such as tanks, ships, aircraft, sported a radio. Indeed, the prevalence of radio technology was a contributing factor to the effectiveness of the German Blitzkrieg but also of the Allied advances of the later years.

In each subsequent conflict, radios became more powerful and, for the most part, smaller, and thus easier for troops to carry.

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Stavros Atlamazoglou

Greek Army veteran (National service with 575th Marines Battalion and Army HQ). Johns Hopkins University. You will usually find him on the top of a mountain admiring the view and wondering how he got there.

Related to: Special Operations

Could France undertake the role of Europe’s nuclear protector? Potentially

What are the differences between the six generations of fighter aircraft?

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page