How Russia uses the media to convey a false image of military prowess

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Russia’s massing of troops on Ukraine’s border represents a significant threat to Ukraine’s sovereignty and the stability of the region at large. But as Russia and NATO continue their staring match in Europe, it’s important to look at Russia’s real military capabilities with objective eyes.

Russia’s military is indeed large and powerful, but Russia is far from powerful enough to win a war against the combined might of the NATO alliance… but the perception that they could may be among Vladimir Putin’s most powerful weapons, and it’s one that didn’t come about by happenstance.

Despite the Cold War ending decades ago and the great threat that was once the Soviet Union giving way to a financially anemic Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin’s Russian regime has managed to remain at the forefront of American defense concerns consistently throughout the modern era. Today, Russia shares the role of antagonist in military strategy discussions and near-peer level opponent training with China, another nation with a significantly smaller military footprint than the U.S. The real threat these nations pose to American security and interests abroad serve as a valuable reminder that a nation doesn’t need to match America’s defense posture beat for beat to pose a legitimate threat to the nation’s defense apparatus.

But China’s far-reaching and expansive military modernization efforts coupled with aggressive policies in places like the South China Sea make China’s massive People’s Liberation Army perhaps the most potent threat to American dominance globally. Russia, on the other hand, primarily poses a direct military threat in Europe. The close proximity of Russian ally Belarus and the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad creates a narrow and arguably indefensible passage between Poland and Lithuania called the Suwalki Gap that has long concerned European and American military officials alike. And of course, Russia’s overt aggression toward its neighboring nation in Ukraine has led to multiple international incidents and our current concern over the possibility of large-scale war on the European continent.

Russian Strengths in the Grey Zone

NATO officials already recognize that a concerted effort to capture the Suwalki Gap made by Russian forces would likely succeed, severing the Baltic states from their NATO allies. While efforts are underway to mitigate this threat, the real strength of NATO’s position comes from the knowledge that Russia’s economy likely couldn’t sustain prolonged warfare at the scale a conflict with NATO would demand. Put simply, Russia’s aggression is often tempered more by its pocketbook than the presence of NATO forces.

So why, then, does Russia seem to dominate American discussions about defense and security, when China’s stated aim of replacing the United States as the world’s diplomatic and economic leader poses a more direct threat to American interests? While a question of this magnitude could be answered in a number of ways, one of the most significant reasons Russia remains the subject of our collective concern is nothing more than good, old-fashioned marketing.

Like the Soviet Union before it, Russia has placed a significant emphasis on “grey zone” operations and narrative management in its foreign policy and military endeavors. Grey zone, in this case, means military operations that lead up to the very edge of overt acts of war, but stop just short of sparking a real conflict. Examples of these sorts of operations include gaining access to America’s electrical grid, conducting assassinations on foreign soil, and even attempts at curbing investigations into their violations of international law, among many others. Russia’s military annexation of Crimea, hacking campaigns against Ukraine’s government, and even their most recent movement of troops into Ukraine’s Donbas region could all be viewed as Grey Zone operations, as they have not yet prompted any declarations of war, but most of Russia’s efforts are more nuanced—or at least less conspicuous.

Reflexive Control and the Russian Narrative

Related: America needs new covert options for great power competition

Russia has made real headway in the narrative realm of geopolitics thanks to its adoption of a practice known as “reflexive control,” dating back to the Soviet era. Reflexive control was perhaps best summed up by Georgetown Security Studies Review writer Annie Kowalewski, who also cited the work of Mark Mateski in her description:

“Reflexive control is a ‘uniquely Russian’ concept based on maskirovka, an old Soviet notion in which one ‘conveys to an opponent specifically prepared information to incline him/her to voluntarily make the predetermined decision desired by the initiator of the action.’”

Reflexive control is not a conspiracy theory imagined by Western researchers, but rather a legitimate military strategy taught in Russian military schools and training programs, as well as included in Russia’s Gerasimov Doctrine, which is a part of the nation’s national security strategy. Reflexive control has been a known quantity in the defense sphere for decades, but despite America’s familiarity with this practice, the nation has still proven susceptible to influence campaigns in the digital age, bolstered by Russia’s adoption of social media as a means to the same ends.

While many would attribute Russia’s efforts to meddle in America’s 2016 presidential election to this practice, a perhaps more valuable example could be in the political havoc that followed. Russian narrative efforts extend far beyond one election or candidate, and in truth, involve nearly every facet of conflict woven into the fabric of American culture. Russian influence campaigns have been attributed to candidates in both political parties, the American debate about vaccination (pre-COVID), and even summer blockbuster movies. Anywhere Russia sees an existing rift between the American people (or the people of any other opposing nation), they work to exacerbate the conflict, weakening opposing nations from within.

But Russia’s narrative control efforts aren’t limited to giving simmering conflicts a signal boost. These same practices are also leveraged to make Russia seem like a more threatening opponent to some, and a valuable distributor of military technology to others.

Using Narrative to Convey Strength

Russia’s annual defense budget tends to hover at around $60 billion, which places them on fairly equal footing with nations like the UK, despite maintaining a force that is significantly larger than that of its spending peers. As a result, Russia has been forced to make hard decisions regarding the allocation of its meager budget—sacrificing the capabilities of its surface fleet at times to bolster spending on new submarines and limiting orders of technologically advanced platforms like the T-14 Armata main battle tank and Su-57 stealth fighter to little more than “token” numbers, as a few examples.

Russia continues to develop these systems, despite the inability to fund their mass production, in part because merely having a military capability is often enough to get your name mentioned in the media alongside more formidable opponents like the U.S. or China. Russia’s troubled stealth fighter, the Su-57, serves as a good example of how Russia develops “capabilities,” that aren’t practical in a fight, but do garner headlines.

The list of operational fifth-generation fighters around the world isn’t a long one: America and its allies have the F-35, America has the F-22, China has the J-20, and Russia has the Su-57 (though there are a number of others in development). Most wouldn’t find that list surprising, but what many might be surprised to learn is that the United States maintains a fleet of literally hundreds of operational fifth-generation jets, while Russia has only 14 or so (only two of which are serial production models, the other 12 are handmade prototypes). Russia’s tiny fleet of stealth fighters wouldn’t represent any real military capability worthy of note, but just having the jet gets them mentioned in the same breath as the U.S.

Likewise with the T-14 Armata, which, unlike the Su-57, is widely seen as a highly capable and technologically advanced platform worthy of the media bluster that surrounds it. However, like the Su-57, Russia can’t afford to put the T-14 into mass production and to date, there are none in service. Once more, despite not offering any literal military capability, Russia manages to stay relevant in the global tank conversation because they have some advanced tank platforms collecting dust in a warehouse somewhere.

Related: Is Russia’s Su-57 the worst stealth fighter on the planet?

Technologies Purpose-Built for Narrative

Of course, the T-14 and the Su-57 are not the only high-profile Russian defense programs to capture headlines in recent years. In fact, it could be argued that both are small potatoes compared to efforts like Russia’s Poseidon nuclear “doomsday” submarine drone, their massive RS-28 Sarmat nuclear ICBM, and of course, their “invincible” nuclear-powered cruise missile.

While each of these weapons represent real threats to Russia’s opponents, they are once again hampered by the inability to mass produce any of them (or in one case, even getting it to work), but that ultimately doesn’t matter. Each of these platforms was purpose-built to offer the Russian government specific leverage when dealing with foreign nations.

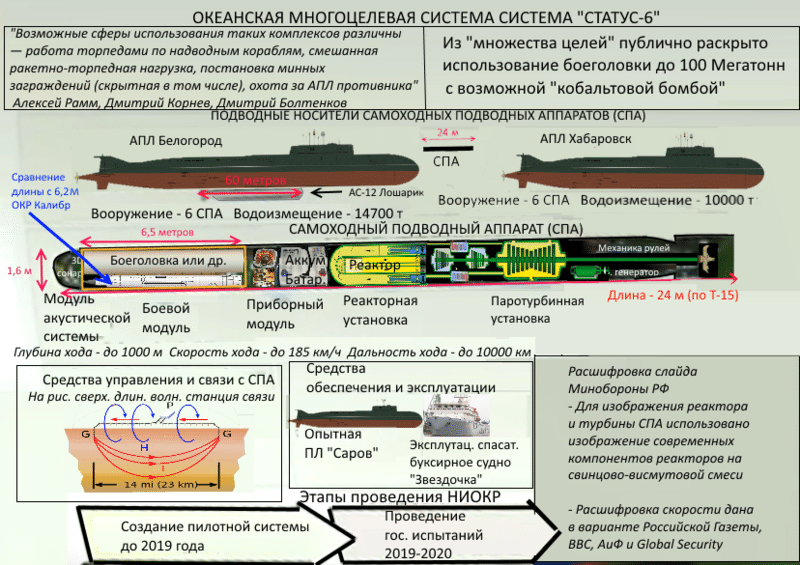

The “Doomsday Sub” Status-6 Oceanic Multipurpose System

There was a time when Russia’s Status-6 (often referred to as Poseidon) weapon was considered an urban legend, but after it was leaked that the U.S. included the weapon in an intelligence report, Russia took advantage of the press coverage and announced that their “doomsday sub” was indeed real.

The Poseidon is a submersible drone equipped with either a 50-megaton or a massive 100-megaton (depending on your source) nuclear weapon that can be deployed by Russia’s large submarines. To provide a frame of reference, the largest nuclear weapon ever detonated had a 50 megaton yield—3,125 times more powerful than the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima—making the occasional Russian 100-megaton claim all the more disconcerting. In practice, the platform would sneak into American coastal waters and detonate, combining the destruction of a massive nuclear weapon with an irradiated tsunami crashing down on shoreline communities.

While this platform may indeed work, it doesn’t actually offer Russia any increase in nuclear capability. Their nukes were already sufficient to hold up their end of the “mutually assured destruction” bargain, making the Status-6 less a strategic weapon (as its use would usher in the same nuclear war we’ve worried about for decades), and more about messaging. Strategic value can only really come from weapons that force a shift in your opponent’s strategy, and Poseidon simply doesn’t. An attack with this weapon would result in the same nuclear armageddon as any other Russian nuke, large or small.

The Poseidon, like the RS-28 Sarmat, is about instilling fear in Russia’s enemies, not about winning an actual fight.

The RS-28 Sarmat or “Satan II”

Related: Russia’s massively powerful nukes are strategic duds

Russia’s latest heavy thermonuclear intercontinental missile carries multiple warheads designed to evade modern missile defense systems and can deliver a whopping 50-megatons of nuclear power to a target. As of this year, the RS-28 is excepted to be coupled with Russia’s hypersonic boost-glide weapon known as Avangard for the same nuclear role in a more maneuverable package. Russia famously qualified the scope of their new missile as powerful enough to destroy a landmass the size of “Texas or France,” and it’s worth noting that this weapon does indeed absolutely dwarf even the biggest nukes in America’s arsenal.

But once more, this weapon doesn’t actually give Russia a new capability. Despite its massive size and intimidating name (Satan II), the use of this weapon would prompt an all-out nuclear response, leading to the very same end-of-the-world scenario a smaller yield weapon would incite. Even the inclusion of hypersonic payloads doesn’t change that reality.

Put simply, it doesn’t matter if Russia launches one or one hundred nuclear weapons at the United States, nor does it matter the relative size of each. The outcome remains the same.

The 9M730 Burevestnik “Skyfall” nuclear-powered missile

Russia’s troubled nuclear-powered missile has yet to function properly in any of Russia’s tests, and may potentially have caused an explosion near Russia’s northern coast as recovery teams tried to salvage a failed missile pulled from the seabed. In theory, nuclear propulsion could give the missile an extremely long-range, allowing it to make sweeping adjustments to its trajectory in order to avoid missile defense systems. In practice, however, it has thus far proven to be a bigger hazard to Russian troops than it is to any others.

This platform could potentially give Russia a capability boost in terms of offensive platforms if they ever manage to get it working and mass produce it. However, with funding for development limited and funding for production unlikely, the real value of this platform may be in garnering more media attention for Russia’s high-tech efforts.

Of course, the U.S. also explored a similar approach to missile propulsion, but the threat of accidentally irradiating huge swaths of land proved so irresponsible that America’s efforts were shuttered in the 1960s.

The Checkmate stealth fighter

Last July, Russia unveiled their new Checkmate stealth fighter, meant to be a single-engine alternative to the larger and far more expensive Su-57. The Checkmate has been touted as a $30 million competitor for America’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, despite existing only as a single wooden mockup and a series of drawings on a piece of paper to date.

But even if the Checkmate were ever to manifest (thus far, no production plans have been announced) it still seems very unlikely that it would live up to the hype. Russia’s first and far more expensive stealth fighter, the Su-57, has famously struggled to go into production for decades, with its first serial production aircraft promptly crashing almost immediately after taking off and only two others being delivered since then.

The Su-57 may be called a stealth fighter, but it boasts a radar cross-section roughly equivalent to America’s notably un-stealth F/A-18 Super Hornet. It stands to some reason that a dramatically smaller price tag on the Checkmate won’t produce dramatically stealthier results.

Turning Narrative into Financing

At this point, we’ve firmly established that many of Russia’s high-profile defense efforts are oriented toward the perception of Russia as a powerful and formidable foe, but that’s far from the only reason Russia works hard to keep its seat at the defense technology table. While Russia’s bluster may help it maintain an air of intimidation when dealing with opponents, the real value to Russia’s long-term defense is in securing foreign investment.

Turkey’s decision to purchase Russian S-400 air defense systems at the expense of access to America’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is a shining example of how Russia is attempting to position itself as the arms supplier for nations that are not in America’s good graces. There are many nations the United States is unwilling to sell advanced weapons to, and by conveying an image of technological might to the world, Russia hopes to position itself as the technological equivalent for those with more nefarious reputations.

This effort has prompted Russia to announce a bevy of headline-grabbing platforms like the Uran-9 infantry robot and claims of “active camouflage” that would allow troops to blend into their surroundings like the Predator. While these technologies tend to fail in actual use, Russia’s state-controlled global media outlets convey them as successes to show the world that Russia is a worthwhile partner in weapons development. By the time it turns out these new technologies are duds, the world’s interest has already moved on.

And therein lies the rub. Many of Russia’s highest-profile capabilities may be less about strategy and more about perception, but by placing this emphasis on securing international sales relationships, Russia may be able to leverage that money to benefit the more serious aspects of their military apparatus—like their growing fleet of nuclear submarines. In a very real way, then, Russia may be “faking it until they make it,” and the prospect that doing so could potentially work is, in itself, a very real threat to American interests overseas.

Read more from Sandboxx News:

- Russia claims to fire warning shots at UK destroyer… But did they?

- Why are Russian fighter jets in Libya and why is that a big deal?

- Plausible deniability: Russian Mercenaries in the Central African Republic (CAR)

- How Russia spies: Active measures & subversion

- Myth or Might? Russia’s ‘groundbreaking’ weapons keep failing

Elements of this article were originally published on 12/28/2020

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart -

‘Sandboxx News’ Camo Trucker Hat

$29.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Military Affairs

A Green Beret remembers his favorite foreign weapons

The AGM-181 LRSO missile will modernize America’s nuclear triad

Navy will soon announce the contract award for its F/A-XX 6th-generation jet, according to reports

America’s new air-to-air missile is a drone’s worst nightmare

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page