Options to counter Russia’s Wagner Group in Africa

- By Divergent Options

Share This Article

This article by Benjamin Fincham-de Groot was originally published by Divergent Options.

Benjamin Fincham-de Groot is a masters candidate at Deakin University pursuing his masters of international relations with a specialization in conflict and security. He can be found on twitter at @Finchamde. Divergent Opinions’ content does not contain information of an official nature nor does the content represent the official position of any government, any organization, or any group.

National Security Situation: Russia’s Wagner Group, a Private Military Company, conducts military-like operations in Africa. As a PMC, Wagner Group’s activities can be disavowed by the Russian government.

Date Originally Written: August 10, 2021.

Date Originally Published: October 4, 2021.

Author and / or Article Point of View: The author believes that Russia’s Wagner Group poses a threat to stability in Africa. This article discusses options to project U.S. influence and protect American interests in the African theatre.

Background: Grey zone tactics are the use of civilian or non-military assets to achieve military or strategic objectives. These tactics are useful for state actors to use or project power while maintaining a plausible deniability that can minimise the chance of conflict escalation[1][2].

Broadly, there are two ways in which state actors work to effect change through grey zone tactics[3]. First, through grey zone tactics a state actor normalises transgressions through small violations that each create precedent to justify a greater violation[4]. Thus, whereas it would be unreasonable for one state actor to escalate to full-blown conflict over a freedom of navigation operation, or a lesser violation of airspace, each unanswered transgression creates precedent for greater transgression without repercussion. One example is the steady escalation of Chinese military flight incursions into Taiwanese airspace[5]. Second, the fait accompli in which a state actor swiftly and suddenly achieves a strategic objective and positions near-peer rivals to choose between escalation and acceptance. This tactic can be pertinent to seizing an objective, extracting a person of interesting, or destroying an enemy asset.

Antulio Echevarria believes that a key aspect of grey zone tactics has been ensuring that no transgression executed as a grey zone manoeuvre is so significant as to elicit a response from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) under Article Five. This article states that any attack on a NATO member state should be treated as an attack on all of them; and that any military attack should be responded to in kind. To stay below the Article Five threshold, grey zone tactics in Europe have primarily been used in the cyber-domain. That said, the definition of what constitutes an attack under Article Five is evolving and has grown to include transgressions in both space and cyber.

Significance: Africa is increasingly become a theatre for great power competition[6]. The United States has a well-established presence there, both military in nature and for peace-keeping operations. China is developing its ability to project power from Africa and within it, and has recently completed its first port capable of servicing Chinese aircraft carriers away from Chinese sovereign territory in Djibouti.

Through 2018 and 2019, pursuant to President Omar Hassan al-Bashir being convicted by the International Criminal Court of war crimes, Sudan was isolated within the global community. It was Vladimir Putin’s Russia that came to Sudan’s aid in supporting Sudan through trade generally, but also supplying Sudan with a significant supply of weapons. Further, when pro-democracy protesters pushed for al-Bashir to step down, the Russian paramilitary contractors known as Wagner Group were unleashed on the protesters.

While officially unaffiliated with Putin, the Russian military or any part of Russian intelligence, Wagner Group nonetheless have ties with Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Kremlin insider[7]. Thus, because of their ties with Prigorzhin and the Kremlin, the actions of Wagner group are considered to be simultaneously enacting the Kremlin’s agenda and projecting Russian power, while also operating as a private military contractor whose behaviour cannot be held against any given state. That is to say, it is a reasonable assumption that any and all actions taken by Wagner Group are on behalf of or towards the strategic goals of the Kremlin, but must be considered as being beneath the threshold of war as they are not representing a state at this time[8].

While primarily operating in Sudan, Wagner Group has been active throughout Africa[9]. Wagner Group uses both gray zone tactics described above, normalizing transgressions and fait accompli. As such, America and their allies and partners allied state actors have two options available to them that would allow them to combat or minimise the impact that Wagner Group are having in the African theatre[10].

Option #1: First, given that American forces are already deployed in the African theatre, it is reasonable that some troops can be repositioned. If Wagner Group were to act on key strategic or humanitarian objectives, they would have to choose between escalating and initiating combat with American forces or abandoning those objectives[11]. As much as openly pursuing Wagner Group assets for their war crimes would be difficult to justify to the United Nations Security Council, and might be seen as the pursuit of Russian nationals; positioning assets to defend strategic objectives minimises the capacity for Wagner Group to achieve Russian strategic goals[12]. This is not to say that these repositioned American forces should patrol endlessly, but rather be positioned around key objectives such that Wagner Group assets must risk greater escalation and greater personal risk in pursuing those strategic objectives.

Risk: This option risks an escalation of conflict between Wagner group assets and the American military.

Gain: This option deters of Wagner Group assets from achieving their strategic goals, and minimizing Russian power projection in Africa.

Option #2: The U.S. could deploy their own paramilitary contractors into the African theatre to counter Wagner Group. These paramilitary contractors, similar to the ones the Americans deployed into Afghanistan and Iraq, could be used to provide strategic pressure, or engage in combat with Wagner Group assets in the event in efforts to maintain the security of key assets. Significantly, the deployment of paramilitary contractors in defense of American and humanitarian assets would reasonably be below any threshold for war, and be unlikely to escalate beyond that initial conflict.

Risk: This option risks an escalation of conflict between Wagner Group and American-employed paramilitary contractors.

Gain: This option protectis humanitarian assets in the African theatre, minimising Russian power projection, and demonstrating American investment in protecting Allied assets. Through the utilization of paramilitary contractors, this also frees up the U.S. military to focus on other threats.

Other Comments: Africa is increasingly a theatre for great power competition. With Russia and China pursuing very different avenues of projecting power onto that continent, America and its allies need to clarify what their goals and strategic aims are in that region; and to what lengths the West is willing to go to in order to pursue them.

Recommendation: None.

Endnotes:

[1] Mazarr, Michael J. Mastering the gray zone: understanding a changing era of conflict. US Army War College Carlisle, 2015.

[2] Banasik, Miroslaw. “Unconventional war and warfare in the gray zone. The new spectrum of modern conflicts.” Journal of Defense Resources Management (JoDRM) 7, no. 1 (2016): 37-46.

[3] Echevarria, Antulio. “Operating in the Grey Zone: An Alternative Paradigm for US Military Strategy.” Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College (2016).

[4] Carment, David, and Dani Belo. War’s Future: The Risks and Rewards of GreyZone Conflict and Hybrid Warfare. Canadian Global Affairs Institute, 2018.

[5] Jackson, Van. “Tactics of strategic competition: Gray zones, redlines, and conflicts before war.” Naval War College Review 70, no. 3 (2017): 39-62.

[6] Port, Jason Matthew. “State or Nonstate: The Wagner Group’s Role in Contemporary Intrastate Conflicts Worldwide.” (2021).

[7] Marten, Kimberly. “Russia’s use of semi-state security forces: the case of the Wagner Group.” Post-Soviet Affairs 35, no. 3 (2019): 181-204.

[8] Rondeaux, Candace. Decoding the Wagner group: Analyzing the role of private military security contractors in Russian proxy warfare. New America., 2019.

[9] Benaso, Ryan. “Invisible Russian Armies: Wagner Group in Ukraine, Syria and the Central African Republic.” (2021).

[10] Belo, Dani. “Conflict in the absence of war: a comparative analysis of China and Russia engagement in gray zone conflicts.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 26, no. 1 (2020): 73-91.

[11] Gannon, J. Andrés, Erik Gartzke, Jon R. Lindsay, and Peter Schram. “The Shadow of Deterrence: Why capable actors engage in conflict short of war.” (2021).

[12] Rizzotti, Michael A. “Russian Mercenaries, State Responsibility, and Conflict in Syria: Examining the Wagner Group under International Law.” Wis. Int’l LJ 37 (2019): 569.

Read more from Sandboxx News:

- Russia’s high profile weapons are all smoke and mirrors

- Special operations forces must look and fight differently for future conflicts

- Just how big is China’s Navy? Bigger than you think

- How Russia spies: Active measures & subversion

- The Russian Air Force is its own worst enemy

Feature image: Security Service of Ukraine

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

A-10 ‘Thunderbolt Power’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Camo Trucker Hat

$29.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Divergent Options

Related to: Military Affairs

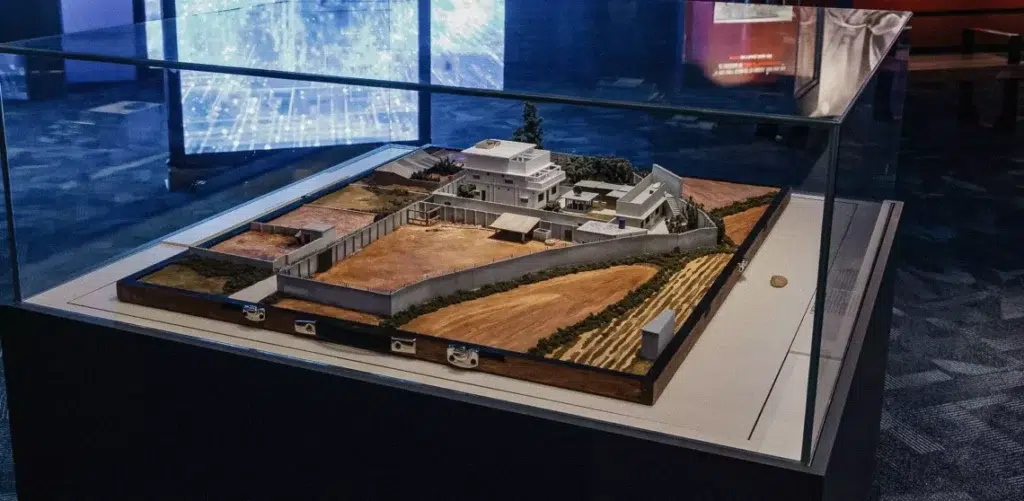

The CIA used miniature models to meticulously plan high-stakes operations

Who dares wins: The importance of defeat in being successful

Marines deploy new system to take out ships in the Pacific

British intelligence once hacked al-Qaeda just to mess with them

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page