No, the Nazis did not invent stealth aircraft. Here’s the real story

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Despite what you may have seen on the internet, the Nazis did not invent stealth aircraft. But let’s talk about why this myth has become so prevalent in recent years.

A big part of it comes from the lackluster reporting of many mainstream news and history outlets eager to capitalize on clickbaity titles about Nazi superweapons over the years. These stories often paint World War II Germany as a terrifying technological juggernaut that was always just on the verge of a new breakthrough that would turn the tide of the war.

There’s no denying that scientists and engineers working under the banner of Hitler’s NAZI party were often at the forefront of their respective fields. In World War II, Germany deployed the world’s first operational cruise missiles in the V-1, and the first operational ballistic missile in the V-2. They also fielded the world’s first jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me 262, though they were fielded too late in the war to make much of a difference.

It’s also no secret that nations like the U.S. smuggled many of these scientists and engineers out of Germany during and after the war, putting them to work on advanced programs that would continue to garner headlines for decades to come.

But in recent years, our human affinity for mystery, combined with society’s growing distrust in governmental institutions, and our subsequent interest in conspiracy theories, have emboldened a small faction on the internet to give Nazis credit for a wide variety of inventions they actually had nothing to do with. Within the aviation circles that I tend to run in, stealth — or specifically, the means to delay or even defeat radar detection — is high among them.

So, let’s put this myth to bed, once and for all.

Related: How Russia uses the media to convey a false image of military prowess

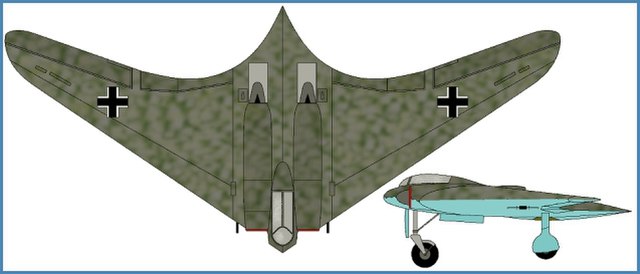

The Horten Brothers’ famous flying wing

The basis for the claim that stealth was actually a Nazi invention is really born out of the works of Walter and Reimar Horten, brothers who began experimenting with unusual airframe designs prior to the outbreak of World War II. They got their big break in 1943 when the head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goering, called for new light bomber designs that could carry 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) of munitions at 1,000 kilometers per hour (620 mph) to targets as far as 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) away.

To make things even tougher, the Nazi commander wanted the aircraft to retain a third of its fuel for combat, meaning it really needed an unrefueled range of some 3,000 kilometers (about 1,864 miles) to manage to trek to the target and back with a third of its fuel reserved for the fight.

The Horten brothers recognized that achieving those speeds with such a payload would require using recently developed turbojet engines, but these high-powered engines came with a huge drawback — they were fuel hungry and inefficient.

The British had made significant leaps in radar technology during World War II, but the Horten brother’s flying wing design wasn’t born out of any interest, or even awareness, that such a design could help delay detection. Instead, they chose it because it was aerodynamically efficient. With no tail surfaces to produce drag and a streamlined flying wing body, their Horten H.IX design was all about reducing the fuel requirements for long-duration, high-speed flight.

And while their design would become the first jet-powered flying wings, flying wings themselves had already been around for a while. The earliest tailless flying wing design may be credited to France’s Alphonse Penaud in 1871, but the first real powered flying wing was actually a biplane called the D.4, which was developed by a British army officer named John William Dunne in 1908.

Just about two years later, Germany’s Hugo Junkers patented his own large flying wing transport aircraft concept, using the same logic the Horten brothers would leverage decades later: a simple and aerodynamically clean tailless wing would allow for better fuel economy to ferry large payloads of passengers and materials across vast distances like the Atlantic Ocean.

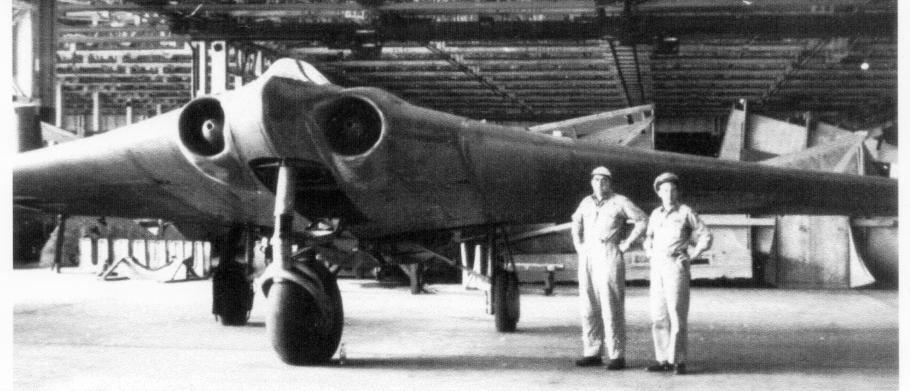

The Horten’s proposal was the only one submitted to the Nazi government that even came close to their requirements, and they immediately set about building an unpowered glider to demonstrate their design. Following a successful flight of the glider, they moved on to building the H.IX V2, often referred to as the Ho 229 V2, which was the same design with the addition of two Junkers Jumo 004 turbojet engines — the world’s first production turbojets to see operational use.

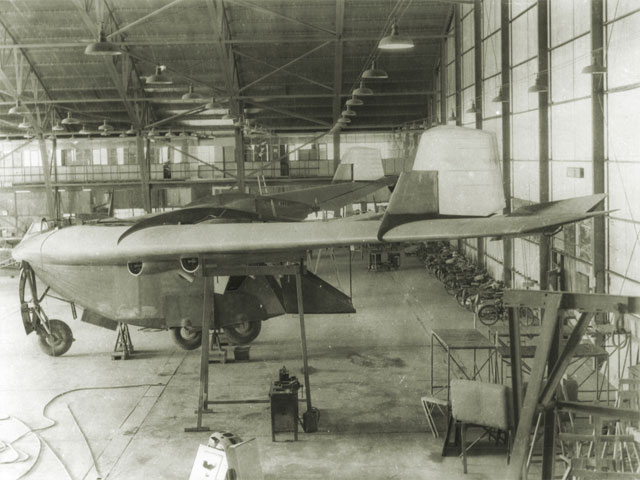

But the concept wouldn’t go much further than that. In February of 1945, the V2 crashed, killing its test pilot, and although the Nazi government ordered 100 of the jets (to be called the Ho 229), the war ended before the third prototype, often called the Ho 229 V3, was even finished.

When the war ended, nobody really cared about the Horten’s flying wing

It’s no secret that Nazi scientists and engineers were working at the very forefront of the technology of their day. As the war came to a close, more than 1,600 of these specialists working under the Nazi banner were recruited to work for the United States under Operation Paperclip, and more than 2,500 others were brought in by the Soviet Union in their own Operation Osoaviakhim. These specialists continued to work on a variety of new programs for each nation in the years that followed, and can often be found named under prominent programs like NASA’s Apollo missions and others.

These very real facts, along with legends about Nazi anti-gravity propulsion drives, hidden Antarctic bases, and even secret moon landings, all served to further the myth that Nazi scientists were not just well-funded and forward-looking, but were somehow decades or more ahead of their global peers.

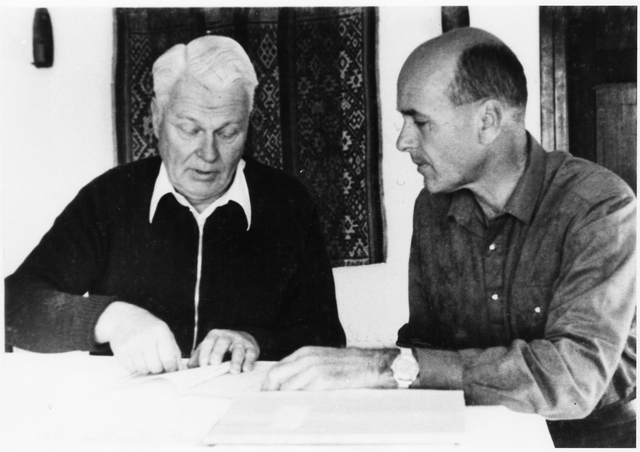

The truth is, the Horten brothers were not blessed with advanced or otherworldly knowledge. That fact becomes apparent when you consider the post-war careers of its inventors. Reimar Horten first attempted to negotiate with both the UK and China for an opportunity to continue developing his flying wings, but after neither expressed any interest, he settled on emigrating to Argentina.

And this is the first place in my research where it became overtly clear that the narrative surrounding the Horten brothers, the Nazis, and stealth was doing more of the heavy lifting in this tale than their actual engineering work ever did. Somehow, according to countless outlets, Reimar Horten was brilliant enough to develop the first stealth aircraft decades ahead of anyone else, but he wasn’t smart enough to realize that Argentina wouldn’t be able to offer him the same level of resources a newly emerging global superpower could.

But even when people are willing to address that point directly, they still bloviate wistfully about what could have been:

“Reimar had fallen on hard times in the 1950s,” Russell E. Lee, curator in the aeronautics department of the National Air and Space Museum, told Smithsonian Magazine. “At that time, Argentina did not have the aeronautical resources of the United States. I don’t think he realized that until after he got there. If things had gone differently, who knows what he could have accomplished?”

Reimar’s continued work would eventually lead to the notably not-stealth flying wing called the FMA I.Ae 38, based directly on the Horton Ho V3 prototype that was never finished. One would expect an aircraft based on the legendary Nazi stealth fighter would have been a resounding success with nearly two decades worth of additional refinement, but instead, it made only one successful test flight before being canceled in 1960.

Walter Horten gave up on pursuing aircraft design and remained in Germany to serve in the nation’s post-war Air Force. If these two enterprising men had actually unlocked the secrets to stealth… it seems remarkably unusual that no nation was interested in learning more about it.

The Horten brothers vs. Jack Northrop

While some of the reasons for internet trolls giving the Horten’s credit for developing stealth can be boiled down to something as simple as their design bearing a passing aesthetic resemblance to the B-2 that would fly decades later, there’s actually more to it than that. Some of it has to do with other flying wing programs that were going on before, during, and after the Horten brothers’ work.

Jack Northrop, the famed founder of the defense industry giant known today as Northrop Grumman, expressed his interest in the gliders being developed by the Horten brothers in the 1930s. He and his firm would go on to develop a variety of flying wing designs for the U.S. military, eventually culminating in the B-2 Spirit. For those who are eager to credit Nazi Germany with the development of stealth, this is one of the elements often pointed to. However, attributing Northrop’s flying wing successes to the Horten brothers’ failure requires omitting a fair bit of important context.

Jack Northrop, born in 1895, began experimenting with flying wing designs in 1929 with his first company Avion — though his first “flying wing” actually had a prominent tail section attached via booms. Walter and Reimar Horten, born in 1913 and 1915, respectively, began their own experiments with flying wing gliders in 1933 as members of the Hitler youth.

In 1940, Northrop fielded his first true flying wing, the N-1M (which stood for “Northrop First Mockup”). The aircraft even performed well enough in testing that it prompted the Air Force to request a design proposal from Northrop for their new bomber program.

This new effort called for a range of 6,000 miles and a top speed of 450 miles per hour, allowing the U.S. to conduct bombing raids against Nazi Germany from across the Atlantic in case England were to fall. His resulting design was the XB-35, which the Air Force agreed to help develop in November 1941… three years before the Horten brothers began their design work on what would become the Ho 229. In fact, the Horten’s first powered flying wing, the H.VIII, made its first flight in 1944.

However, the XB-35 design was prop-driven, while the Ho 229 was jet-powered, making it a more advanced approach.

And to be clear, the Ho 229 V2 did take flight more than three years before Northrop’s first jet-powered flying wing, the YB-49. By that point, Northrop’s team did have access to the wreckage of the Horten brothers’ prototypes, but Northrop himself didn’t seem to think much of them.

“Forget it, they’re just glider designers,” he reportedly said of the Hortens.

Of course, that’s not to say that the Northrop team didn’t glean anything from the Hortens’ work. It’s safe to say neither he nor his team would be eager to advertise any lessons learned from recovered Nazi hardware, and as is always the case in aviation, advances made by one nation often inform the advances made by others.

But the fact of the matter was, Northrop and the Horten brothers could be seen as contemporaries in the flying-wing field. The idea that Jack Northrop got the idea for flying wings from the Hortens, and that idea somehow birthed the B-2 a half-century later, is more about keeping the myth of Nazi stealth alive than it is about any real history.

Related: Here’s your first look at the B-21 Raider, America’s new stealth bomber

Reimar Horten was better at inventing myths than stealth fighters

Reimar Horten may not have been able to garner any real interest in his flying wings outside of Argentina, but that didn’t stop him from making grandiose claims about what his design could have been throughout the remainder of his life. If anything, it was Reimar’s claims in the 1980s that became the basis for the myth of Nazi stealth that led to the rest of the narrative gymnastics we’ve come across thus far.

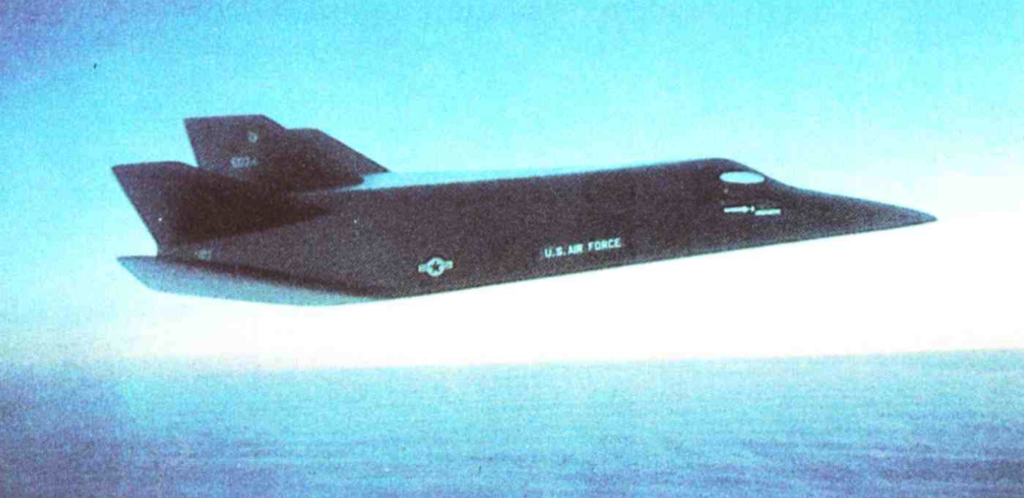

It’s important to understand that, although the U.S. didn’t acknowledge that the F-117 was operational until 1988, and didn’t give the world its first glimpse of a real stealth aircraft until 1989, stealth itself was a very open secret for years before that. During the 1980 presidential election, the Carter administration disclosed that there was a stealth “plane” in development to curb criticisms leveled by Reagan over the cancelation of the B-1 program. By 1982, America’s “secret” stealth bomber was already a part of budget discussions in the New York Times, and by 1986, shows like “The A-Team” were referencing stealth bombers in their plot lines.

So it comes as little surprise that in 1983, Reimar Horten took advantage of all the new stealth aircraft hype to reinvent the Horton Ho 229 as a Nazi stealth aircraft.

According to Reimar, he had always intended to combine sawdust, charcoal, and glue and apply it between the layers of wood that made up most of the Ho 229’s external surfaces.

He claimed that “the charcoal should absorb the electrical waves. Under this shield, then also the tubular steel [airframe] and the engines [would be] invisible [to radar].”

Now, in 1983, this struck some as feasible, but of course, today, we’re well aware of the complex chemistry involved in producing polymer (or ceramic) radar-absorbent materials. If mixing charcoal with sawdust could actually reduce an aircraft’s radar return, maintaining the F-22 would be quite a bit cheaper. But just to be on the safe side, a Northrop Grumman team analyzed the surviving remnants of the remaining Horten 229 V3 to look for any signs of this radar-defeating charcoal mixture — and they believed that they did indeed find some.

“During our inspection of the Horten 229 at the Smithsonian museum, it appeared that a material similar to carbon black or charcoal was mixed in with the glue between the thin layers of the leading edge shape,” their peer-reviewed paper states.

So they used a portable radar reflectometer called the Next Generation Sensor to assess the return created by the leading edge of the aircraft’s center section… and found that it actually created a greater return than their control sample, which was just a 3/4″ inch piece of plywood.

“The Ho 229 leading edge has the same characteristics as the plywood [control sample] except that the frequency [do not exactly match] and have a shorter bandwidth. This indicates that the dielectric constant of the Ho 229 leading edge is higher than the plywood test sample. The similarity of the two tests indicates that the design using the carbon black type material produced a poor absorber.”

And to make matters worse for Horten’s claims, a subsequent analysis conducted by the National Air and Space Museum during the aircraft’s restoration concluded via digital microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and Fourier-transfer spectroscopy tests that there was no actual charcoal in the glue after all – which, along with there being no mention of this “stealth” concoction in recovered documents pertaining to the Ho 229’s development, all suggests the whole story was nothing more than a fabrication that was given much more credence than was ever warranted.

But that wouldn’t be the last time Horten’s claims would be given far more credit than they deserved…

National Geographic and “Myth Merchant Films” brought Reimar Horten’s unfounded claims to the mainstream

In 2009, National Geographic released a Northrop Grumman–sponsored “documentary” made by Myth Merchant FIlms called, Hiter’s Stealth Fighter that went pretty far out of its way to portray the Ho 229 not only as the world’s first real stealth aircraft, but potentially even one that could have helped the Nazis win the war.

Of course, by now, it should be clear that neither of these claims is true, but it only gets worse from there. In a commercial for the documentary, the narrator claims that the “only surviving Horton 229 has remained hidden in the shadows and away from prying eyes,” later claiming within the documentary that the aircraft was being stored in a “secret government warehouse.”

The real truth is that it was stored outside in Chicago for a time before being moved to the Smithsonian’s restoration facility in Maryland (which is hardly a secret), where it sat for 60 years – spending some of that time in an open wood shed.

For the sake of the documentary, Northrop Grumman invested $250,000 into building a replica of the Horton Ho 229 V3. They then bombarded it with radar to assess just how stealthy it really was. Their analysis revealed “moderate radar-deflecting properties,” which the documentary presented as undeniable proof that this Nazi stealth fighter was the real deal, saying outright that their findings revealed, “just how close Nazi engineers were to unleashing a jet that some say could have changed the course of the war.”

If you’ve ever watched an episode of Ancient Aliens, you’re probably already familiar with the qualifier “some say” as a means to presenting utter nonsense as fact simply because some say it.

Editor’s Note: We did have a YouTube video that discusses the inaccuracies depicted in “Hitler’s Stealth Fighter,” but despite our work clearly falling within the legal framework of “Fair Use,” Myth Merchant Films filed a copyright claim against us to have the video taken down.

But what about the Northrop Grumman teams’ findings that the aircraft replica they assembled did offer “moderate” radar deflecting capabilities? Well, that also required a fair bit of creative liberty. As Stephan Wilkinson pointed out in his excellent write-up on the topic in 2020, making the Horton Ho 229 that stealthy meant leaving out most of the things that made it a fighter, a bomber, or even an aircraft.

The Horten brothers’ original design included an 11-foot-wide center section made of welded steel tubing that Northrop left out of their replica. The Ho 229 also had two early turbojet engines… which Northrop also left out of their replica. They also left out the Ho 229’s eight large aluminum fuel tanks, and perhaps most importantly of all, the aircraft was designed to carry munitions externally, but they didn’t include any of them either. In effect, they omitted all of the elements of the wooden aircraft that would have produced the most prominent radar returns, and then called the result moderately stealth.

Related: Fighter Comparison: Russia’s stealth fleet ranks 11th in the world

The Nazis didn’t invent stealth, and the Horten brothers were no visionaries

The Horten brothers did absolutely develop and fly the world’s first jet-powered flying wing, and that alone earns them a place in discussions about the flying wings that would follow — but the idea that these two young men were engineering visionaries so far ahead of their time that we’re still struggling to catch up is nothing more than the Horten’s own efforts to rewrite history and the sensationalized story-telling that leaned on their narrative for the sake of ratings, readers, or clicks.

The Ho 229 never actually existed — and instead manifested only as a dream of what could have been if the aircraft’s powered prototypes had eventually produced an operational aircraft. Those prototypes were groundbreaking, in large part, because by 1943, Nazi Germany was willing to throw money at anything that might help them win the war. Flying wings weren’t new at the time, but sticking expensive new turbojets into them was.

These aircraft weren’t exotic glimpses of the future – by most accounts, they were poorly assembled and riddled with design flaws. The Ho 229 V2 prototype that actually flew, for instance, was nearly impossible to fly at first because Walter Horten determined its center of gravity using a measuring tape that was missing its first 10 centimeters, famously skewing the aircraft’s balance so much that the test pilot said he could barely keep it airborne with the stick pulled all the way back. When he landed, the aircraft hit so hard that it damaged its landing gear as a result. Of course, even after fixing that issue, that same prototype would later crash — killing its test pilot.

If World War II had never happened, the Horten brothers may have had promising careers as kit airplane and glider builders, but almost certainly not as the forefathers of stealth.

The truth is, Jack Northrop got a lot wrong in his comments over the years about the Horten brothers, but he hit the nail on the head about one thing…

“Forget it, they’re just glider designers.”

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart -

‘Sandboxx News’ Camo Trucker Hat

$29.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Military History

Game-changing military aircraft that were canceled before they could change the game

Anduril’s Roadrunner is a unique reusable missile interceptor

The AGM-181 LRSO missile will modernize America’s nuclear triad

Navy will soon announce the contract award for its F/A-XX 6th-generation jet, according to reports

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page