Military draft registration is going down, so Congress wants to take action

- By Hope Seck

Share This Article

Shortly after the United States entered World War I in 1917, military enlistment encountered a major crisis: the Army failed to meet a target of one million new volunteers. Even with the nation’s entry into an existential conflict that would be known as “The War to End All Wars,” only about 73,000 new recruits had signed up in the first month of fighting.

Congress and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson took decisive action, creating the U.S. Selective Service System (SSS) on May 18, 1917. All of a sudden, military-aged men could be conscripted and required to fight for their nation, facing up to a year in prison if they refused. More than 2.8 million conscripts were shipped off to fight in World War I, and notable draft registrants (though they weren’t conscripted) included baseball legend Babe Ruth and escape artist Harry Houdini.

While the military draft was shut down in 1920 following the end of the war, conscription would return in future conflicts. World War II saw more than 10 million draftees; Korea saw 1.5 million, and Vietnam more than 1.8 million.

The last draft order in U.S. history was issued in 1972, and the American all-volunteer force was formally established the following year. But after a pause of several years, President Jimmy Carter issued Proclamation 4771, establishing an ongoing draft registration requirement for male citizens aged 18 to 25. This meant the nation, on short notice, could resume conscription from ready rolls of registrants.

The existence of the SSS, which now operates out of an ordinary-looking office building in Arlington, Virginia, has continued to provoke controversy over the years. As recently as 2016, bills were introduced in the House and Senate to abolish the military draft for good. The same year, a “Draft Our Daughters” amendment that would add women to draft registration made progress toward passage, despite its author only having introduced it for shock value.

Related: And you have my axe: The American lumberjacks of World War I

Throughout all of this, the requirement and means of Selective Service registration have remained the same: young men, ideally within 30 days of turning 18, need to register with SSS online or by mail. Often, they’re prompted to do so when completing other processes like obtaining a driver’s license. If they don’t, they’re ineligible for federal loans and grants and may, in theory, face up to five years in prison or a fine of up to $250,000.

Yet, nobody has been prosecuted for non-registration since 1986, and the link between federal student aid and registration compliance was recently dissolved.

But the system is now facing a new crisis: how to respond to declining registration rates. According to the SSS’s 2023 annual report, registration declined from 15.6 million in 2022 to 15.2 million last year, for a national registration rate of 84 percent.

“This was largely driven by the loss of the requirement for men to register with SSS to receive Federal student aid and the removal of the option to register on the Free Application for FAFSA form,” the report stated. “These were both outcomes of the passage of the FAFSA Simplification Act in 2020. This method of registration historically accounted for approximately 20 percent of all annual registrations nationwide.”

Faced with dropping registration rates and an increasingly toothless enforcement policy, Congress is now trying to take action. The National Defense Authorization Act for 2025, the annual defense policy and budget bill that will likely see passage before the end of the year, includes two different proposals that would make draft registration automatic, rather than optional.

The House version of the NDAA would automatically register with SSS every male citizen and legal U.S. resident who otherwise meets requirements. The Senate version would go a step further, automatically registering “every citizen” and every legal resident within SSS parameters. This version, for the first time, would add young women to the SSS.

Related: The Marine Corps is not struggling with recruiting and this may be due to its unique nature

For this version of the bill, the change would not be immediate, but would take effect within two years of the NDAA’s passage. After that, young people would get notices in their mailbox informing them they had been registered – no action necessary.

Apart from cultural discomfort over the possibility of women being required to serve, there could be downsides to the automatic registration policy.

“Automatic registration could potentially reduce costs for the SSS that would normally be used for advertising and outreach to encourage registration,” the Congressional Research Service stated in a report on the new legislation. “On the other hand, continuing to require proactive registration could serve as a reminder to individuals of their civic obligation and may even encourage individuals to consider volunteer military service.”

In any case, an automatic registration requirement would be a historic update to a system that has been in place in some form or another for 107 years.

But will the SSS ever be used once again as a mechanism for military conscription? That’s an entirely different question. As the Center for a New American Security think tank outlined earlier this year in its report on bringing back the draft, it wouldn’t be easy – and likely wouldn’t happen as quickly as Congress and the president might want. Fewer Americans who meet military fitness and education standards might pose a problem to mass mobilization, the report noted, and social media might become weaponized for resistance against the government.

On one thing the report was completely clear: the U.S. shouldn’t return to military conscription unless it finds itself in a war that leaves no other choice.

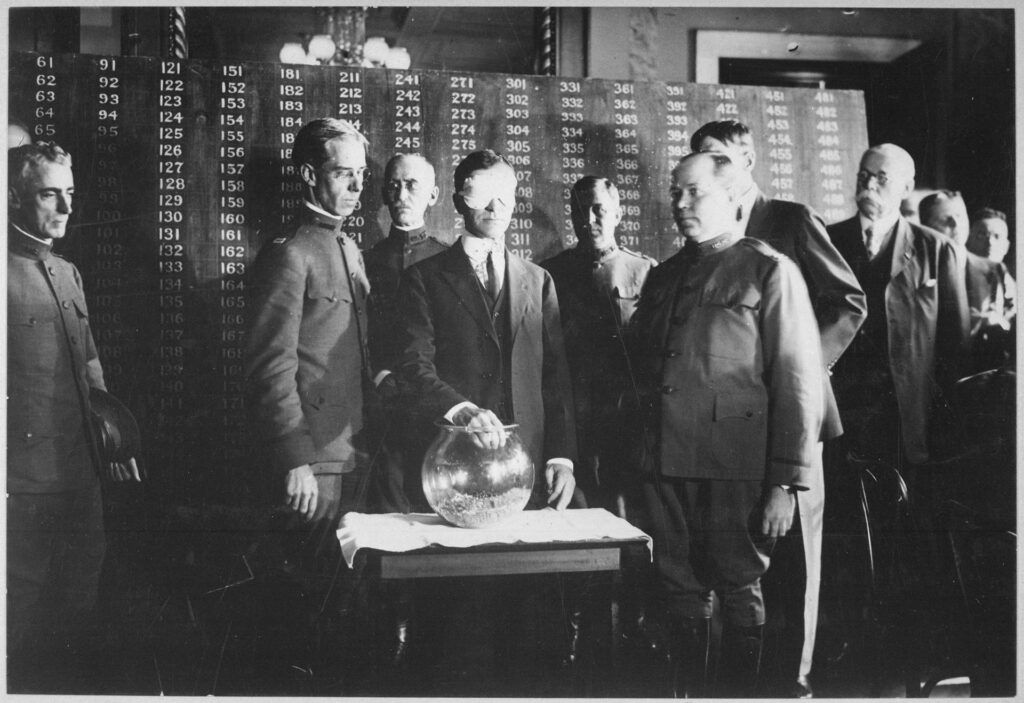

Feature Image: On 20 July 1917, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, blindfolded, drew the first draft number in the lottery to be called up: Number 258. Those drafted were to serve in the American forces during World War I. (Wikimedia Commons)

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Marine Corps new marksmanship plan will make Marines more lethal

- Weird incidents with South Korea’s elite Tuk Su Bu Dae unit

- Stolen stealth fighter: Why China’s J-20 has both US and Russian DNA

- Floyd Nichols’ handcrafted WWII knives never achieved wide fame but are now collectible

- Top 3 foreign policy questions for the new Trump administration

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

A-10 ‘Thunderbolt Power’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Hope Seck

Hope Hodge Seck is an award-winning investigative and enterprise reporter who has been covering military issues since 2009. She is the former managing editor for Military.com.

Related to: Military Affairs

What it’s like to visit Korea’s Demilitarized Zone

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page