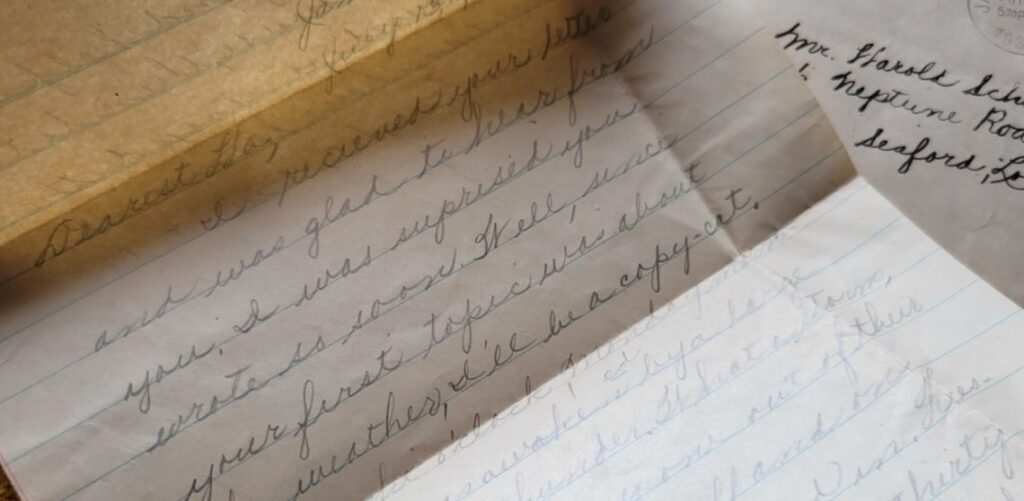

Letters to Loretta: Young admiration and peaceful days

- By Kaitlin Oster

Share This Article

Editor’s Note: Sandboxx News presents a World War II series by Kaitlin Oster on the power of hope, letters, and love in seeing us through the terrors and agony of war. You can read the other installments here and listen to Kaitlin’s radio interview about the series here, or visit her website here.

The tall, narrow homes and straight brick buildings of Jamaica, Queens stood in neatened order like soldiers at attention. Each structure was uniform on the outside, save for little window boxes, a chain-link fence, or the occasional vegetable garden. Inside, the homes of Jamaica were varied with families bustling about, doing what daily tasks could be done in the Depression. Children ran barefoot, played hide and seek, or searched for an open space to play stickball. The Reilly family was one brood with five children – there had been six, but the youngest had passed away when he was very small. The Reilly children were known for having a mother on the police force – something not common. They were also known for swiping potatoes from the kitchen when their mother was at work, roasting them in back alleys, and eating them plain.

Only a few houses down from the Reilly’s, in an identical structure, was the Schwerdt family. The mother and father, both German immigrants who had left Europe before World War I, raised a family of 10 children, the youngest two being identical twins. The twin boys had bright red hair and bright blue eyes and their own mother was unable to tell them apart. Their father, John, was a brewer – and at one point a milkman. In the economic downturn of the United States, his skills as a brewer were in great demand from the general working class. His wife, a homemaker, spent her days making and repairing clothes and raising the 10 children.

This tangle of youths, generally unsupervised – especially in the summer months – made the most of their time by adventuring outside and exploring what there was to do for free during the Great Depression. They ran around in dirtied clothes, equal parts oblivious and affected by the poverty that haunted most families in the 1930s, not just the children of immigrants.

One day, one of the German twins, Harold, made his way to the playground at the end of the block. Oftentimes it was crowded with other children, but on this particular evening, there seemed to be only a smattering of playmates. The sun sank behind the brick horizon of New York as Harold reached a swing set occupied by one other.

“Hello,” the young girl said as he sat down on a swing, leaving one between them. “I like your hair.”

Harold felt himself blush. She was very pretty, maybe 14 years old to his 16.

“Thank you. I’m Harold Schwerdt. What’s your name?”

“Loretta Reilly,” she replied. The children sat in a comfortable silence peppered by the squeak of swing chains, and the occasional honk of traffic. They learned that their homes were very close, and Loretta believed she had seen Harold a week earlier, down by an ice cream shop.

“Oh, that was probably Arthur, my identical twin,” Harold replied. “Y’know our own mother can’t tell us apart?”

Loretta laughed. “Wow, identical twins. You must do everything together.”

“Well, most things. He’s more of a prankster. My mother says I’m too serious for my age.”

The low glow of the setting sun was spreading when suddenly, someone called “dinner!” Loretta stirred a moment before hopping off her swing.

“That’s my mother. It was nice meeting you.”

“Maybe you can find me by the ice cream shop one day, and I’ll buy you a cone,” Harold said. He stood to tip his head to Loretta, and from the opposite direction of the block he heard, “Abendessen!”

Loretta wrinkled her eyebrows. Harold shrugged a little and chuckled, a little embarrassed.

“erman. It means dinner.“

“Oh, you speak German?”

“No, not really,” he admitted. “Our parents prefer us to speak English. But when my siblings and I are out and we hear someone hollering German, we know it’s our mother.”

“That is very clever,” Loretta laughed, “and ice cream sounds lovely.”

The two agreed to meet again at the playground towards the end of that week. Before he left, Harold shook Loretta’s hand.

“It was a pleasure meeting you, Loretta Reilly.”

“Likewise, Harold,” she pronounced his last name slowly and produced, “Schwartz,” but he didn’t dare correct her. Harold believed, at 16, that he had found love at first sight.

July 13, 1938

Dearest Harold,

I received your letter and was glad to hear from you. I was surprised you wrote so soon. Well, since your first topic was about the weather, I’ll be a copycat. At eight o’clock, Monday morning I was awakened by a large crash of thunder. What a storm it sent everyone out of their beds. It rained off and on all day, so I stayed in. Tuesday, I got up at ten thirty and it was so warm, I sat around and listened to the radio all day. Tuesday night Evelyn, Lil, and I went to see Albie. He has a heavy cold. Today, I got up at ten thirty and helped around the house, then to the playground. I stayed there about an hour then came home. Tonight, I went to a meeting, then to Nachlin’s. Later, Harry took several of us including Lil, Betty, Gert, Ed W., Eppie, and myself to the night baseball game on Hillside Ave. I go in at 11:30 and boy! Did I get a balling-out.

Now, I must ask you how is everyone, if they look as well as they did Sunday. They are swell. Oh! Pardon me. How are you? As far as missing you, I do (not). Hoping to see you soon I’ll close.

Affectionately yours,

Your Honey (I hope)

Loretta (chubby in your eyes)

P.S. The Old Gag. Excuse pencil and paper writing.

Also, give regards to the family.

(the perfume is my sister’s) xxx

Read more from Sandboxx News

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Kaitlin Oster

Related to: Military History

This is how Navy SEALs conduct “over-the-beach” operations

A Delta man’s failure to follow instructions was more than it seemed

Soldiers in Alaska landed their Black Hawk on a train in a special ops exercise

Fixing the US Navy’s shipbuilding problems starts with the workers, agency analysts say

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page