Letters to Loretta: The situation in the POW camp is getting desperate

- By Kaitlin Oster

Share This Article

Editor’s Note: Sandboxx News presents a World War II series by Kaitlin Oster on the power of hope, letters, and love in seeing us through the terrors and agony of war. You can listen to Kaitlin’s radio interview about the series here or visit her website here.

February 20, 1944

Kriegsgefangenenpost

My Darling Wife;

Your packages were eagerly received and well worth their weight in gold. To date I’ve received 5 parcels, of which 3 were cigarettes. The contents of the other two were quickly devoured or put to urgent use. I’d like to add that vitamin pills will be appreciated. I’m getting your letters, but very irregular. I’m anxiously awaiting our wedding picture. I hope [you’re studying] earnestly to master the accordion. T’would be a great delight to be serenaded by the music your nimble fingers choose.

Half the letter gone, and I haven’t once mentioned that I love you. Believe me doll, I do love you. What else could it be that causes you to appear in my every undertaking? Your hair, eyes, lips are seen with animated enjoyment. The letter must close but the love I have here within for you shall never cease.

All my love,

Ha

The winter in the German POW camp continued to be unforgiving. Harold was becoming almost entirely reliant on what Loretta and his other family members were sending him from the United States. He knew then after receiving his care packages in February that the next shipment probably wouldn’t come around until April or May.

Harold found himself feeling weaker and his weight dropped more than he had ever noticed before, although he hadn’t seen his own reflection in months. He noticed the veins in his arms becoming more prominent, the hair on his head felt thinner, and his teeth hurt. With only a few hours of running water a day – and it was never hot – the men were resolved to burning the remainder of the outdoor latrines down in order to keep warm. They were still sleeping regularly two – sometimes three – to a bed, which would mean anywhere between six and nine men per bunk, to prevent freezing.

Related: Letters to Loretta: A series into the power of humanity to persevere during war

Commandant Kuhn had promised ample blankets to the Americans as well as the other prisoners of war, but it was obvious that the Germans didn’t care what the soldiers received. Tensions were high as the men banded together to split blankets – more like tablecloths, Harold thought. There were maybe two blankets to every three or four men, and they hardly did a damn thing. They never saw the belongings that had been stolen by the guards a month prior; the Red Cross rations seemed to be less and less as well. The soldiers were used to receiving one package per man, and they found themselves sharing more often now. It was vital to have shoes on at all times so that their toes didn’t freeze off. The close quarters increased the risk of illness and the sick bay was overwhelmed with disease – mostly skin and upper respiratory infections.

All of this became routine.

The men couldn’t fight the guards – they had guns and dogs. Harold loved dogs back home, but hated these dogs. These shepherds were extensions of the SS, trained to attack any man who got “too” out of line – or not out of line at all. But the guards didn’t seem to need any real excuse to beat, or even kill, Americans. When a soldier was killed by an SS, some men with their spirits beaten down would say, “They shouldn’t have ran,” or, “They shouldn’t have tried to escape.” But there was no need to use such forces on men who weren’t even granted three square meals a day. With the camp population swelling further beyond capacity each week, and the German rations cut in half only a month earlier, tensions continued to escalate across the camp.

“This is due to the rich supply of the Red Cross food.” Commandant Kuhn looked for any excuse to make the men suffer wherever possible, wherever he could squeeze them a little tighter.

The lack of food, the cold, and the three doctors available to the Americans made some of the men begin to lose their minds. One prisoner was admitted for being mentally ill. The other men had noticed for a while their fellow slowly and surely slipping into a state of delusions and paranoia. The doctors available to the camps weren’t trained in this type of condition. Harold felt sorry for the man who was unable to discern real from fake. Then again, Harold often woke up wondering whether or not he was truly living in POW camp Stalag XVII-B, even after almost a year of imprisonment. When the man was finally admitted, they wished him well and hoped he would gain some healing in the medical ward; at least he was safe there in his hospital gown.

Related: Can older candidates make it through special operations selection?

One bitter morning in March was broken with screams. A French doctor tried to calm the mentally disturbed prisoner, but it was obvious that the man was disillusioned. The prisoners – those feeling well enough to rouse from bed that early – made their way through the freezing barracks to see what was happening. The shouting only got louder until Harold and the others saw the shadow of the patient run towards the boundary fence, his feet crunching and catching in the frozen, muddied ground. A guard, on alert, began to yell at the prisoner, only frightening him more as he picked up speed and ran faster in his hospital pajamas away from the medical barracks. His dressings flapped around in the bitter cold. Clearly, he was ill to be running in such minimal clothes.

“Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot! He is ill!” The French doctor chased after the man, waving his arms to garner attention from the SS who at that point released his pistol from the holster. The patient huffed to a part of the fence – free of electrical charge – and began to climb. Frantic, the doctor began to yell louder to get the patient to get down off the fence. He was pleading, screaming for the SS to hold fire as the man was clearly out of his mind.

“No! No!” The men watched from the barracks, helpless to the situation. If they left their barracks they’d be beaten, maybe even shot themselves. They looked on at this twisted dance between SS, doctor, and sick man.

Related: Nazi Germany’s V-2 vengeance missile: The first human object to reach space

A loud crack rang out, piercing the morning air. Smoke trailed from the barrel of the guard’s pistol like a snake as the doctor slowed down and looked on, his hands limp at his sides. A dog, startled by the gunshot, began to bark and its shrill cries stung Harold’s ears. The patient, upon hearing the screams of the doctor, turned around on the fence to look behind him. The SS took the opportunity and shot the man through his heart. He exhaled hard. They were far away but Harold could see the victim’s hot, white breath curl from his mouth and up into the morning as if his soul was leaving his body. His hand released from the fence, his body falling limp and bloody onto the frozen ground. The doctor, who hadn’t stopped running, arrived to his aid.

“You killed him!” He knelt in the dirt and held the dead man’s head in his hands. He cursed the guard in French. The blood soaked through the prisoner’s hospital pajamas and for only a moment, Harold wondered if they would discard the clothing or recycle it for the next patient. The guard holstered his pistol and instructed the doctor and other guards to dispose of the body. The men in the barracks looked on, said nothing, and eventually peeled themselves from their witness stands and returned to their bunks – dead men walking. They could never win in here, it seemed.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The SR-72 timeline: From initial design to ‘Top Gun’s’ Darkstar

- Ukraine set off 4 explosive devices on a freight train operating on the only major railroad connecting Russia and China

- Operation Olympic Games: The first cyberweapon

- The favorite games of BUD/S instructors that SEAL candidates suffer through

- Garrett STAMP – The Marines nearly got a weird flying jeep during the Cold War

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

Kaitlin Oster

Related to: Military History

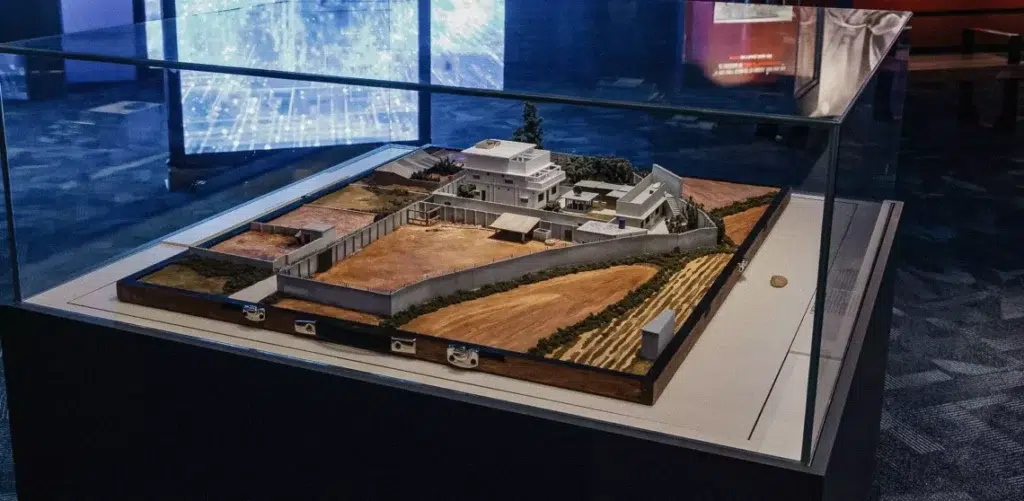

The CIA used miniature models to meticulously plan high-stakes operations

Marines deploy new system to take out ships in the Pacific

British intelligence once hacked al-Qaeda just to mess with them

The Space Force wants its own boot camp

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page