Initially pitched to Japan as a fighter that could counter emerging threats posed by China, Lockheed Martin’s proposed F-22/F-35 hybrid may have been a losing financial proposition, but if it had come to fruition, it would have been the most capable fighter the world had ever seen.

America’s F-22 Raptor is widely considered the most capable air superiority fighter in history, but its dated avionics, expensive maintenance, and abbreviated production run have doomed the platform to an early demise. With just 186 Raptors delivered before its production facilities and supply chain were cannibalized in favor of F-35 production, America’s Raptors are an endangered species the Air Force now expects to begin phasing out of service in the early 2030s.

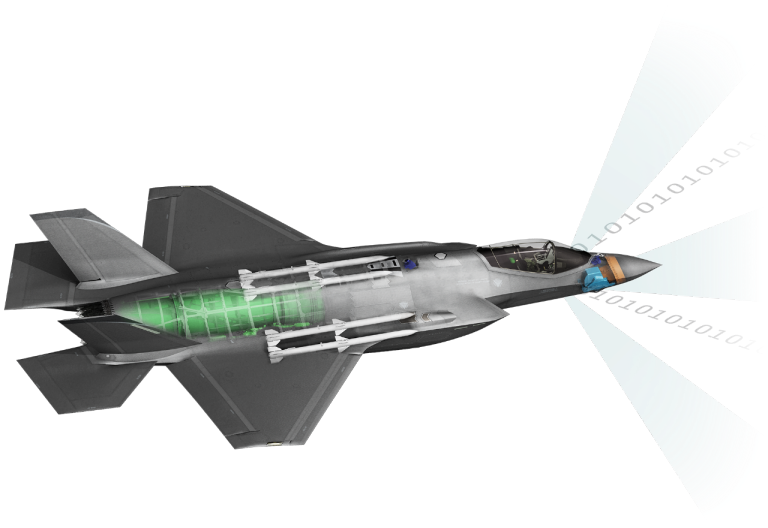

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, on the other hand, lacks the Raptor’s hot rod performance. But what it lacks in horsepower, it makes up for in the most advanced data-fusing suite of avionics ever fielded in a tactical aircraft. And while the capabilities offered by the F-35’s computer power may not seem as sexy on paper, the advantages they provide are so pronounced, they are actively reshaping how countries approach air warfare.

Combining these two already-legendary platforms into a single hybrid aircraft would have resulted in the most broadly capable and dominant fighter ever to fly, eclipsing both of the jets it would be based on and emerging as the new yardstick by which all future fighters would be compared. But for all the hype such a fighter rightly deserves, the concept itself came just a bit too late to make financial sense.

Why fielding a hybrid F-35/F-22 fighter made perfect sense for both the U.S. and Japan

America famously canceled F-22 production less than a third of the way through its initial order in 2011. At the time, some 20 years since the fall of the Soviet Union and with the U.S. embroiled in counterterrorist operations on multiple fronts, American lawmakers just didn’t see the value in funding all 750 stealthy Raptors originally intended as replacements for the venerable F-15 Eagle. As a result of that limited production run, America’s Raptors cannot be replaced as they age out of service or if shot down by enemy contact, which means they’re ultimately destined for an early demise. Older fighters like the F-15 and F-16 don’t face similar issues because, despite their age, both of these jets are still in production.

In February 2017, the Air Force submitted a congressionally mandated study about restarting F-22 production. The study concluded that getting the line running again and building 194 new aircraft would cost the government approximately $50 billion (or more than $61 billion in today’s dollars). All told, each new F-22 would cost approximately $216 million in 2016, or $265 million today. If the production order was smaller than 194, say, 75, as indicated in a separate RAND report cited by the Air Force, the unit cost would be closer to $266 million in 2016, or a whopping $326 million today.

Compare that to the per-unit price of the similarly airstrip-reliant F-35A, at just $77.8 million, and new Raptors don’t look nearly as promising. The F-22 is an incredible jet… but is one Raptor really better than three F-35As?

America’s longstanding ally Japan signed on to start buying F-35s all the way back in 2011, but with Russia’s Su-57 and China’s J-20 both operating nearby, it began looking for new air superiority fighters to replace its aging F-15J fleet. And that’s where Lockheed Martin stepped in.

According to Lockheed’s proposal, they could provide Japan with a hybrid fighter that combined the sensor-fusing power of the F-35 with the dogfighting chops of the F-22 for just $177 million per aircraft (about $208 million today). And while the U.S. would have to sign off on such a deal, it could have huge benefits for Uncle Sam too.

Kickstarting production of this new fighter for Japan would allow the U.S. to procure new hybrid fighters to supplement its anemic Raptor fleet, rather than investing in older air superiority jets like the F-15EX.

Related: The F-15EX may be the baddest 4th-gen jet on the planet

… Right until it didn’t

A hybrid F-22/F-35 fighter may offer all of the best capabilities fielded by these jets, but we’re still talking about aircraft that began flying in 1997 and 2006, respectively. By 2018, when this concept was first proposed, advancements in stealth, sensor technology, and material sciences meant a hybrid fighter would be quite dated by the time it would start reaching American or Japanese runways.

With the immense costs associated with standing up new fighter production lines in mind, it simply made more sense to begin clean-sheet development on newer, even more advanced fighters that would ultimately cost about the same per airframe as a dated hybrid fighter. Today, the U.S. is doing just that with the Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance program and the Navy’s new F/A-XX fighter that are in development. Likewise, Japan is now partnered with the U.K. and Italy to field their own next-generation fighter.

But if somehow, it had made good financial sense to field a Joint Strike Raptor, the result would have outclassed everything in the sky by a wide margin… at least, until 6th-gen fighters emerged to take the crown.

How to build a hybrid F-35/F-22 fighter

It’s important to remember that this concept never made it out of the proposal stage, which means outlining how an F-22/F-35 hybrid fighter would look, fly, and fight will require a fair bit of creative license. To that end, we’ll approach this concept by combining the right elements of each fighter, as outlined by Lockheed Martin’s statements and publicly disclosed systems found in each platform.

What that really amounts to is taking the F-22 as it is today, complete with dynamic aerobatic performance and the smallest radar cross-section of any fighter in history, and adding the F-35’s advanced avionics and other elements meant to reduce operating costs or increase capability.

We’ll work from the outside-in.

Design & Propulsion

This new aircraft would leverage the overall design layout of the F-22 Raptor, and, indeed, would look a great deal like the F-22s that are already in service. As such, our Joint Strike Raptor would also leverage the same two Pratt & Whitney F-119-PW-100 afterburning turbofan engines found in the current F-22. These engines produce a whopping 70,000 pounds of combined thrust under afterburner, and would likely deliver similar performance to today’s F-22s, with a top speed in the neighborhood of Mach 2.25 and a thrust-to-weight ratio of right around 1.25 with a combat load and a half-full tank of fuel.

This combination of airframe design and power production would give our new hybrid fighter the same supercruise capabilities offered by today’s Raptors — meaning the aircraft would be able to sustain supersonic speed without using its afterburner, conserving precious fuel for the fight and flight home. The thrust vector control offered by this design and engine pairing provides not only excellent aerobatic performance in a close-quarters fight but, perhaps more importantly, an effective means of controlling the aircraft while engaging at high angles of attack.

Radar Absorbent Skin

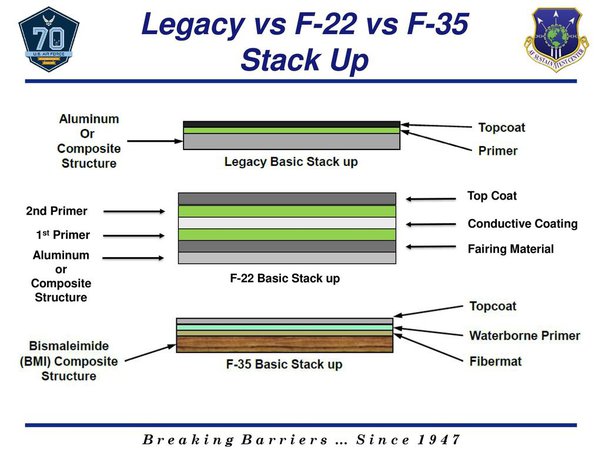

Despite the outward appearance of the F-22, this aircraft would leverage advancements incorporated in the radar-absorbent materials of the F-35. Radar absorbent materials (RAM) are essential for maintaining the stealth profile of such a fighter, with modern materials rated to absorb upwards of 70-80% of inbound electromagnetic energy or radar waves.

However, RAM is highly susceptible to damage caused by heat, friction, and exposure to the elements. Maintaining, repairing, or replacing these materials represents a significant portion of the high maintenance costs associated with the F-22 and F-35. But the F-35 offers a generational leap in material resiliency that would be incorporated into our new hybrid jet, bringing down the overall cost per flight hour of our new JSR.

Today, the F-22 Raptor costs a reported $85,325 per flight hour to operate, whereas the F-35A rings in at just $33,600 per flight hour. This difference can be attributed to multiple design differences, with more resilient and maintainable RAM being one of them. As such, it can be expected operating costs of a new Joint Strike Raptor would fall somewhere between these two figures, and would almost certainly be lower than current F-22 costs.

Avionics

The F-22 Raptor may be a dominant air-to-air fighter, but its dated avionics suite prevents it from being as capable as it could be. By incorporating the advanced, modular, and broadly classified capabilities of the F-35 into an F-22 airframe, the result would be an aircraft without a peer anywhere on the globe.

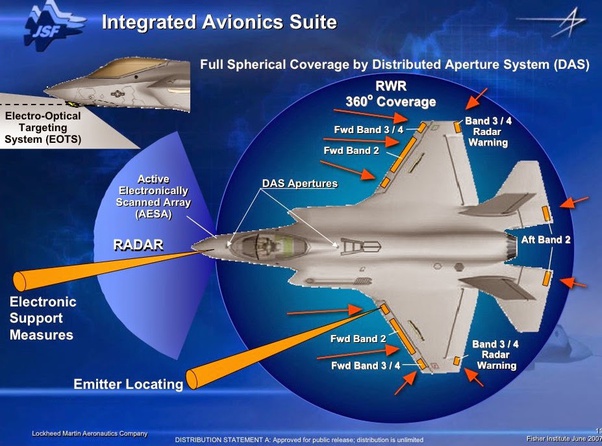

The three most prominent operational shortcomings of the Raptor’s current avionics include a lack of infrared search and track (IRST) capability, the inability to target aircraft “off-boresight,” and the inability to directly network with its more modern counterpart, the F-35, as well as other nearby networkable assets. A new hybrid F-22/F-35 fighter would resolve all these issues and then some, adding significant new offensive and defensive capabilities, some of which remain undisclosed.

Infrared search and track

Infrared search and track capabilities are essential for engaging modern stealth fighters in air-to-air combat. They are, in effect, passive thermographic cameras that can spot and identify the heat produced by enemy fighters even when they’re too stealthy to spot on radar. Advanced IRST systems like the Eurofighter Typhoon’s PIRATE can spot subsonic fighters from more than 50 miles out when facing away from them, and more than 30 miles out when approaching them head-on. The F-22 Raptor does carry the AN/AAR-56 advanced missile launch detector, which may offer a very limited IRST-like capability, but our new hybrid fighter would boast the F-35’s far more advanced AN/AAQ-37 Distributed Aperture System.

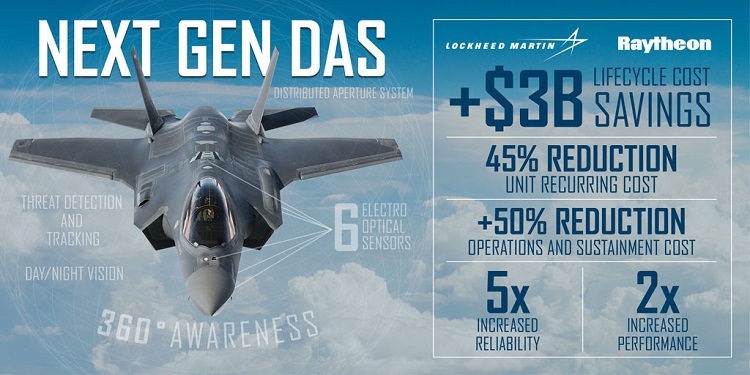

The AN/AAQ-37 is a dual-band system that can read both Middle Wavelength Infrared (for long-range detection) and Long Wavelength Infrared (for detection through fog or smoke) signatures, and unlike front-facing IRST sensors, it’s comprised of six IR sensing cameras positioned around the airframe to provide full 360-degree coverage. Under nighttime conditions, pilots can use the display in their helmets to look directly through the aircraft at targets

This offers F-35 pilots unprecedented degrees of situational awareness, and, when coupled with the F-35’s AN/AAQ-40 Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS), provides IRST functionality as well. This system would be carried over to our new hybrid fighter, representing a massive leap in capability over today’s Raptors.

Targeting System

Today’s Raptor may be incredibly maneuverable, but it needs to be because of the constraints of its current targeting systems. Because of the cramped quarters of the Raptor cockpit, the F-22 has yet to field a helmet-mounted Electro-Optical Targeting System, and as a result, the Raptor can not leverage advanced air-to-air weapons, like the AIM-9X, to their fullest extent. A different cockpit canopy that allows for a larger helmet would be incorporated into our new hybrid fighter to carry this capability over from the F-35.

So, while today’s Raptors must orient the nose of the aircraft toward a target to lock on and fire, our hybrid fighter’s weapons and sensors would follow the pilot’s line of sight, allowing the pilot to engage targets off-boresight, or in other words, when they aren’t directly in front of the jet. The AN/AAQ-40 Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS) our hybrid fighter would carry over from the F-35 coupled with the DAS in the pilot’s helmet display to not only let the pilot see targets to the side or behind the aircraft, but to actually engage them using weapons like the AIM-9X.

The AIM-9X is the latest iteration of the legendary Sidewinder missile. Its modernized systems and thrust-vectoring nozzles allow for a great deal of flexibility in target engagement, including high off-boresight targeting. What that really means is the F-35, and our hypothetical hybrid, can even hit targets with the AIM-9X that are flying behind them. The latest AIM-9X-2’s being fielded with the Air Force and Navy can even be launched without a lock on a target aircraft — leveraging a data link to the fighter for guidance until the target is acquired.

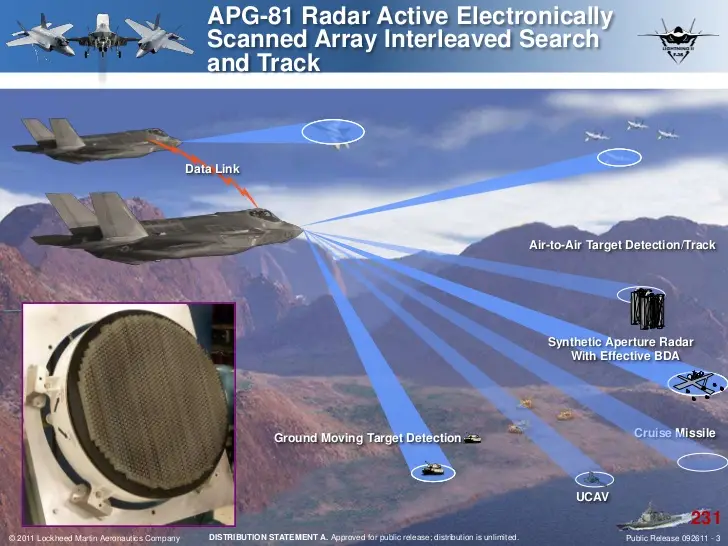

Radar

The F-35’s AN/APG-81 active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar is the direct descendent of the AN/APG-77 found in the Raptor, though more modern F-22s came equipped with the AN/APG-77v1 system that likely offers comparable target acquisition performance. However, our new fighter would leverage the F-35’s radar suite nonetheless, thanks to its integration into the rest of the avionics package and its superior electronic warfare capabilities.

The array can also work in concert with the aircraft’s AN/ASQ-239 Electronic Warfare system to identify enemy radar and broadcast a frequency-specific signal directly at it, allowing the fighter to jam enemy radar with its own while still leveraging the system for target detection.

This jamming capability is not as powerful as the AN/ALQ-99 electronic warfare pod carried by the EA-18G Growler, but because it’s able to broadcast in very precise “beams,” it doesn’t need to be. The growler’s beamwidth is roughly 40 degrees wide, while the F-35’s is just two degrees – meaning it can deliver energy more precisely, allowing it to jam just as effectively with a great deal less power. It’s important to note, however, that the Growler can broadcast in all directions, while the F-35’s jamming capabilities are limited to systems in front of the aircraft.

The F-35’s electronic and cyber warfare capabilities are largely still hidden behind the classified veil, but they very evidently extend well beyond mere jamming. One distinct possibility is the ability to leverage the F-35’s AN/APG-81 not just to jam enemy air defense systems, but to transmit algorithms via a data stream that can actually infect those systems with malware that can be used to monitor signals received, disrupt the function of the system, or even display decoy radar returns.

The final product: A fleet of new Joint Strike Raptors

With the F-35’s advanced avionics and improved radar absorbent skin, and the F-22’s high-performing but low-observable airframe, the resulting fighter would likely be more than the sum of its parts. With a radar cross-section of just 0.0001 square meters, this aircraft would produce a radar return some 1,000 times smaller than Russia’s Su-57, while still providing all of the intelligence gathering, sensor fusing, battlespace managing capabilities that have the Air Force so frequently touting the Joint Strike Fighter as a “quarterback in the sky.”

And all in an airframe that can supercruise, exceed Mach 2, and, if need be, even do this:

But despite how capable this aircraft could be, it arguably would not be the most capable jet the U.S. or Japan could field for the money. The F-22’s aerobatic performance, some could argue, is a relic of a bygone form of air combat – harkening back to a time when engagements weren’t decided from well beyond visual range.

There’s no denying that, with modern technology, it is possible to field an even stealthier platform; one that can delay detection even against stealth-busting, low-frequency, early-warning radar arrays. There’s also no denying that the United States and Japan are looking for fighters that can offer larger payloads and a big increase in range, with an eye toward the sprawling expanses of the Pacific. So, the truth is… an F-35/F-22 hybrid could make for an incredible jet, but not the right jet for the types of conflicts the two countries are working to deter.

The 6th-generation fighters in active development today likely won’t boast the same aerobatic performance we could get out of our hybrid fighter, but will almost certainly outpace even our hypothetical jet in every other conceivable way.

The fact of the matter is that maintaining a decisive air combat advantage deep into the 21st century would take more than the best designs that started being developed in the 20th. And that’s why this incredible fighter never made it off the drawing board.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in February 2023.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- How have American military rations evolved in the last century

- British F-35s faced off against their American counterparts in rare showdown

- Watchdog reveals F-35’s readiness rates – and they’re not looking good

- How a Delta Force operator celebrated New Year’s in Bosnia

- Ukraine is much better at combined arms operations than Russia