How Pearl Harbor changed America forever

- By 1945

Share This Article

Eighty years ago tomorrow Kido Butai, the carrier strike arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy, struck the American naval base at Pearl Harbor. Several US Navy battleships were disabled or destroyed, leaving the Pacific and Southeast Asia open to Japanese attack. Over the next few months, Japan would conquer the Philippines and several British and Dutch Pacific colonies. It would take almost four years for the United States to destroy the Imperial Japanese Navy and force Japan to surrender. The impact of Pearl Harbor on the US national security state would endure much longer.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was psychologically shattering for a generation of American policymakers. The success of the attack resulted from careful Japanese planning and a series of American intelligence failures. The US government was aware that the potential for a Japanese attack was extremely high, and had alerted Army and Navy installations across the Pacific. It knew that Japan had studied Pearl Harbor closely, and was aware of the Royal Navy’s recent attack on the Italian naval base at Taranto.

Policymakers laid the failure to anticipate Pearl primarily at the feet of faulty intelligence sharing procedures. The Army and the Navy each had responsibility for intelligence collection, but did not necessarily cooperate well with one another. The State Department collected diplomatic intelligence but did not work well with the military services. Indeed, even within the Army intelligence sharing was not well-handled; Army staff in the Philippines were slow to use intelligence collected elsewhere in the theater, leading to disastrous unpreparedness when the Japanese arrived. Overall, the US government lacked the capacity to make a good strategic assessment of Japan’s decision-making process, leading to a complete misunderstanding of Japan’s priorities.

Related: How the National Security Act of 1947 changed the US military forever

The US immediately appreciated the need for a centralized, professionalized intelligence service, but had little experience in operating one. In part on the basis of advice from the British, the United States established the Office of Strategic Services in June 1942. This organization would become the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), formally inaugurated in 1947. The OSS would primarily act as an operational intelligence organization, leaving intelligence collection and analysis mostly to the services.

In the wake of the war, the United States government was determined to anticipate and prevent another surprise. Much else had changed. The Army and Navy remained at levels of mobilization unimaginable in the years before the war. In 1947 the National Security Act broke the Air Force away from the US Army, created the Department of Defense, and founded the CIA. Many of the intelligence reforms would focus on the process of aggregating and integrating intelligence collection.

Related: American Spies: How the US collects intelligence around the world

Perhaps most importantly, realization of the implications of the nuclear age dawned upon the US national security elite. The attack on Pearl Harbor merely destroyed a portion of the Pacific Fleet. After the Soviet Union acquired nuclear weapons, a surprise on the scale of Pearl Harbor could kill millions of Americans and render the nation defenseless. Thus, the creation of new, permanent intelligence agencies would focus on developing an integrated operation that would facilitate the collection and sharing of intelligence from many sources. Rebecca Wohlstetter’s 1962 book Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision helped crystalized our understanding of intelligence failure. Wohlstetter’s work confirmed the verdict that poor information sharing had made Pearl Harbor possible and informed future thinking on intelligence sharing between agencies.

Of course, it is in the nature of bureaucracy to sprawl and over the years things became rather less centralized. The services were loathe to give up their own intelligence gathering and analysis sections and retained them. The Federal Bureau of Investigation adapted to the new reality and integrated its domestic intel-gathering capabilities into the new system. The National Security Agency came to focus on signals collection. The Intelligence Community now consists of eighteen separate organs which, despite the best efforts of policymakers, jostle and contend against one another for turf and influence.

This jostling played at least some role in the failure to anticipate the September 11 attacks. The signs of an impending attack were clear in retrospect, but the failure to understand our opponent meant that information was not shared with the urgency the situation demanded. The shock of September 11 drove some reform to the community, but not the kind of wholesale rethinking that the country saw after World War II. Thus, to great extent, the national security state still lives in the world that the attack on Pearl Harbor created.

Read more from Sandboxx News:

This article by Robert Farley was originally published by 19FortyFive.com.

Feature image: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

1945

Related to: Military Affairs, Military History

Video: US military sends aircraft to help with LA fires

Video: DARPA wants to arms a missile with cannons

How a Delta Force operator celebrated New Year’s in Bosnia

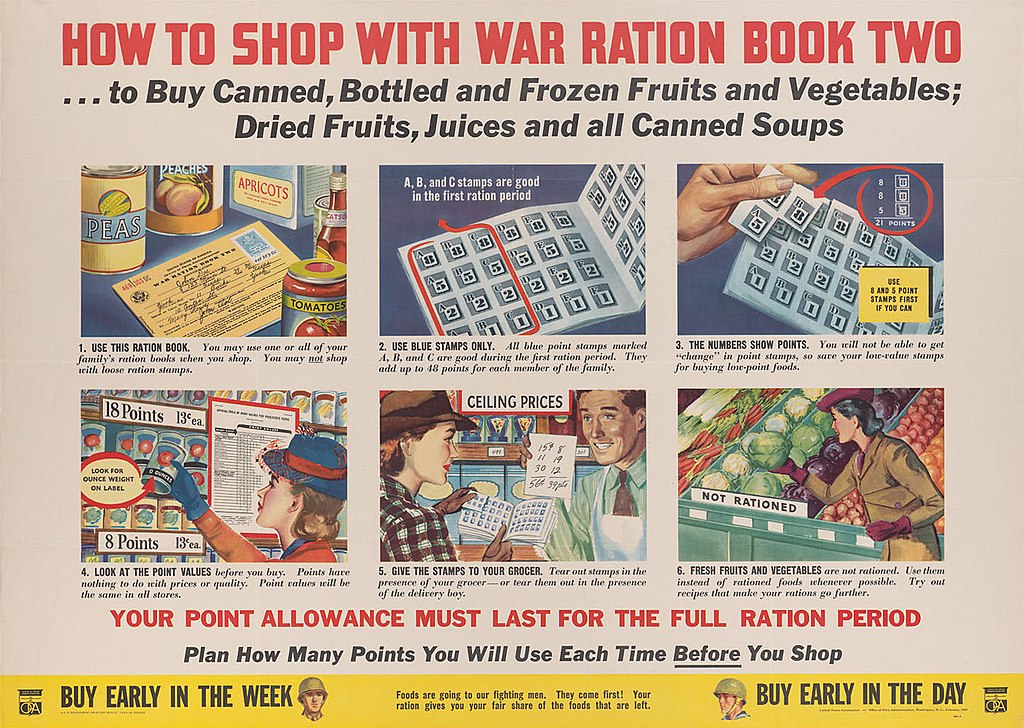

How have American military rations evolved in the last century

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page