How F-14 and F-15 pilots trained to take down the legendary Blackbird

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

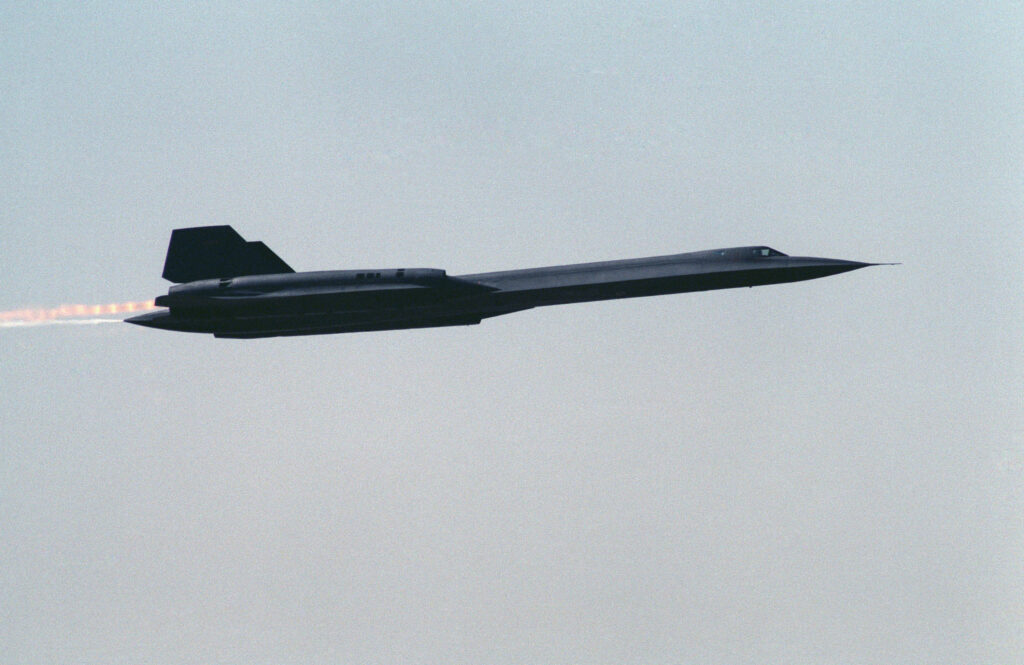

Despite flying into the sunset nearly a quarter-century ago, Lockheed’s legendary SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance plane was so far ahead of its time that even today, some 59 years since its first flight, there has yet to be a single aircraft to challenge its position atop the podium of fastest crewed jets in history. Throughout its three decades of service, the Blackbird famously had over 4,000 missiles of all sorts fired at it, and managed to outrun every single one.

But no aircraft is invincible and the Blackbird was no exception. With looming concerns about high-speed Soviet fighters closing the capability gap that insulated the SR-71 from intercept, the Air Force decided to pit its Mach 3+ Blackbird against America’s own best fighters, both of which have also become legends in their own right: the U.S. Navy’s Grumman F-14 Tomcat and the U.S. Air Force’s McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle.

And while no Soviet fighter or missile ever managed to catch up to the sky-storming Habu (a name pilots gave the Blackbird due to its aesthetic similarities to the pit viper of the same name), the same can’t be said for the simulated AIM-54 Phoenix and AIM-7 Sparrow missiles notionally lobbed its way by America’s top fighter pilots. Like any prizefighter with an undefeated record, the SR-71’s official tally may show only victories, but its unofficial training record is actually littered with defeats at the hands of its slower-moving (but highly capable) American fighter siblings.

But don’t let those simulated defeats fool you… because taking on the Blackbird and winning required a fair bit of meddling that stacked the deck in the fighter’s favor.

Related: How hypersonic drones could defeat missiles the same way the SR-71 did

The truth about air combat exercises (and what we can learn from their outcomes)

As Sandboxx News has covered at great length in the past, training exercises are rarely organized in a way that allows the superior platform to flex its distinct advantages to their fullest extent. Those sorts of exercises do occur in the form of platform and system testing, but the rules of engagement in complex combat training operations usually aim to level the playing field to some extent in order to give all pilots and crews involved some experience working from a tactical deficit.

In other words, commanders intentionally set the rules to give pilots experience fighting or surviving in uncomfortable circumstances, even if their aircraft are so capable that uncomfortable situations are unlikely. F-22 Raptor pilots, for instance, are regularly disallowed from beyond-visual-range engagements during training exercises against other fighters and are sometimes even required to keep their heavy drop tanks underwing when scrapping in close quarters – both conditions set by operational planners in order to nerf (or diminish) the Raptor’s greatest combat advantages.

But if you think the F-22 is often forced to fight with one wing tied behind its back, you’ll be downright shocked at the lengths SR-71 pilots would go to just to make themselves a viable target for America’s premier fighters. And when the fastest pilots in the sky got tired of losing and started breaking those training rules, not even the F-15 Eagle – the fastest fighter in American history with an unmatched modern air combat record of 104 wins and zero losses – could touch the legendary Blackbird.

Related: The King is dead: Why would America want to retire the F-22

Pitting the SR-71 against the Air Force’s F-15 Eagle

The McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle program might be described as an American overreaction to alarming assumptions made by the Defense and Intelligence communities about the Soviet MiG-25. When the first images of this high-speed new fighter reached the Pentagon in 1967, its massive turbojet nozzles, vast wing area, and broad, gulping intakes led many to believe it was the most capable fighter ever seen to that point. In response, the U.S. redoubled its development efforts for a new air superiority fighter that might be capable of standing toe-to-toe with what certainly seemed to be a new Soviet juggernaut.

Of course, the MiG-25 was nothing close to the high-performer the United States feared it to be, but by the time American officials found that out in 1976 (when Soviet pilot Victor Belenko defected with one), the monster they built to take it on – by then known officially as the F-15 Eagle – had already entered service eight months prior.

However, as dominant as the F-15 would prove to be in air-to-air combat, even it struggled against the Habu’s elusive combination of speed, stealth, and electronic countermeasures.

In the books, The Complete Book of the SR-71 Blackbird: The Illustrated Profile of Every Aircraft, Crew, and Breakthrough of the World’s Fastest Stealth Jet, and, SR-71 Revealed: The Inside Story, former Blackbird driver and retired U.S. Air Force Colonel Richard H. Graham discussed his time flying high-speed sorties against the legendary F-15 over the Nellis Air Force Base training range, not far from the clandestine installation many of us know today as Area 51.

The intent of these exercises, which the pilots took to calling Eagle Bait sorties, was to give F-15 pilots valuable practice intercepting high-altitude and fast-moving targets that only the Blackbird could simulate.

“To maximize scare, high-altitude/high-speed intercept practice for the fighters against the SR-71,” Graham wrote. “We stacked the deck in their favor to avoid a multitude of missed intercepts, and consequently, wasted time.”

But as powerful as the F-15 was, it faced all the same challenges as the Soviet MiGs. In fact, in order to give the Eagle a shot at scoring a kill against the Habu using the longest-range air-to-air missile available to it at the time, the AIM-7 Sparrow, the Eagle drivers had to be given special permission to exceed the jet’s safety envelope.

“In order to get high enough to take a reasonable shot at us, F-15 crews were given special permission to do a zoom-climb to 50,000 to 55,000 feet before a simulated AIM-7 launch against the SR-71,” Graham recalled. Flying to these altitudes in an F-15 wasn’t just a question of power, however. It also raised concerns about pilot safety inside the cockpit. “They had permission to be above 50,000 feet for a maximum time of 90 seconds without wearing a pressure suit.”

As they’d soon learn, the Eagle also struggled with approaching the Habu from head-on because its targeting systems weren’t designed to be able to see something closing with them so quickly. As former SR-71 pilot Dave Peters would later recall, the speed gate (a filter set to narrow down radar returns to only legitimate threats) had been set to 1,500 miles per hour.

“We were casually warping along from 1,850 to 2,000. So, for them, we didn’t exist,” Peters said. Yet, even once that issue was sorted out, the F-15s still had a steep hill to climb.

As part of “stacking the deck” in the Eagle’s favor, the SR-71 crews were instructed to fly along a specific flight path at altitudes no higher than 70,000 feet and speeds no greater than Mach 2.8. They even began executing fuel dumps, leaving a massive streak of jet fuel in the sky to help the F-15s find them overhead.

Similar to the F-22’s dogfighting conundrum, these rules rounded off the sharper edges of the Habu’s capability set, giving the Eagle a fighting chance.

When that proved not to be enough, Blackbirds were instructed to fly over a designated point in space (called the intercept point) and even call out their approach to it over open radio frequencies at one-minute intervals starting five minutes out. This approach, however unrealistic, gave the Eagle drivers the window of opportunity they needed, rapidly scoring simulated kill after kill against the SR-71 as it zoomed by.

“After each mission, we would debrief by phone, and the F-15 drivers would report ‘four AIM-7s launched, four kills on the HABU,'” Former SR-71 pilot, Capt. Steve “Griz” Grzebiniak later recalled.

Related: Project Oxcart: Why you had to be married to fly the CIA’s fastest jet

Teaching the air-to-air champ a lesson

Even with all of the allowances the Blackbird drivers made for their competition, just shaking one of the notional AIM-7 Sparrows launched by the F-15s was simple. The now-dated AIM-7 carried only a semi-active radar guidance system onboard, meaning it needed target information to be relayed from the launching aircraft all the way until impact.

The SR-71 carried an advanced electronic countermeasures system onboard that, among other things, has been said to be able to discern between radar transmission and even broadcast phantom returns that would force the engaging fighter to re-acquire the real target. Because of the Sparrow’s semi-active homing guidance system, the Blackbird could dismiss an inbound Sparrow with the flip of a switch.

But as the F-15s racked up victories, the competitive spirit of the Habu drivers began to take hold… and finally, they decided to break a few rules to inject a bit of humility back into the fighter pilots below.

This time, they didn’t execute a fuel dump at five minutes out like usual… mostly because they were flying 16,000 feet higher (now at 86,000 feet) and much faster than before… now cruising at Mach 3.2. The F-15s never had a chance.

“In the phone debrief after the mission, the F-15 flight lead reported ‘four shots and four kills’ on the first pass and mumbled something about radar problems and no kills on the second pass,” Grzebiniak said. “Even with the world’s best planes, pilots, and missiles, it would take a golden BB [a lucky blind shot by the enemy] to bring down a Habu.”

Related: Sea Eagle: America’s plan to put the F-15 on aircraft carriers

The F-14’s AIM-54 Phoenix Missile may have been the real Top Gun

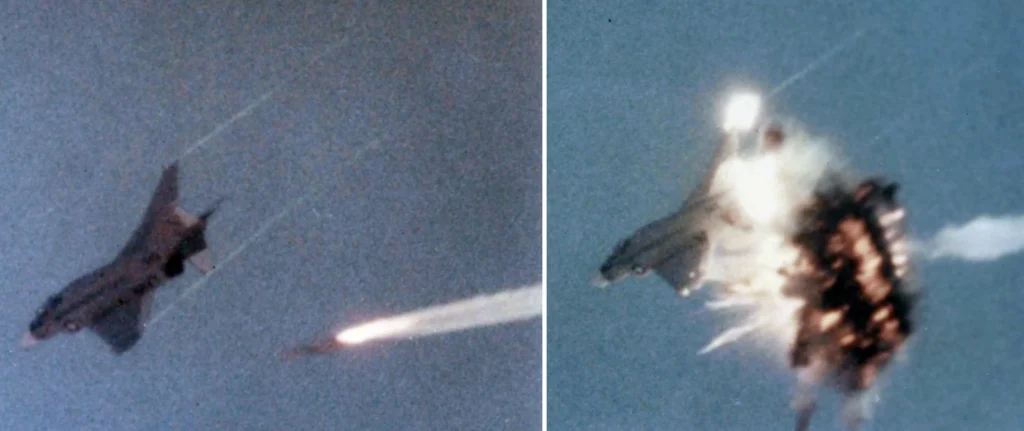

The F-15 wasn’t the only top-tier fighter in the U.S. arsenal at the time, and the truth is, the Navy’s famed F-14 Tomcat of Top Gun fame was actually better equipped for these sorts of high-speed intercepts.

While the Eagle’s AN/APG-63 was a highly capable radar, it fell well short of the massive power output and multi-targeting capability of the Tomcat’s AN/AWG-9 radar and fire control system. With around double the detection range of the Eagle’s radar and the ability to track 24 targets simultaneously, the F-14 could guide six separate missiles into six separate targets at the same time. Despite being based on a fairly dated design, there wouldn’t be a more powerful radar installed in a fighter until the F-22 Raptor entered service.

But perhaps even more important was the Tomcat’s armament, because the F-14 came equipped with the now-legendary AIM-54 Phoenix missile – the longest-ranged air-to-air missile on the planet at the time that flew with a combination of a semi-active seeker to take cues from the F-14’s radar and an active radar-homing seeker for terminal guidance. In other words, once the Phoenix was close enough to a target, it could rely on its own onboard radar to close in, rather than needing the launching pilot to maintain a lock until impact.

Training intercepts that pitted the F-14 against the SR-71 were known by insiders as Tomcat Chase sorties, and were usually carried out over the Pacific, rather than the Nevada desert, thanks to the presence of F-14-hauling aircraft carriers at sea. As with the F-15, Habu drivers did their best to give the F-14 a fighting chance, flying along straight, predetermined flight paths at lower altitudes and speeds than they would normally do. They also maintained open radio communications, allowing the SR-71 pilots to guide the F-14s into their relative positions so they’d have a chance to fire their notional AIM-54s.

The Blackbird flew with its transponder on, and again, without its defensive electronic countermeasures engaged. But, again, even in these very favorable conditions, Tomcats struggled to find their mark.

“The 14s could find us but they couldn’t do anything until we modified and gave them times, route of flight, speed, and altitude beforehand so they could have a pre-planned setup,” Pilot Dave Peters recalled. “The 15s didn’t do that well for quite some time.”

Tough as it was to spot the Blackbird zooming past, once the Tomcats did, the Phoenix missile was capable enough to pose some real problems for the Blackbird. With a top speed in excess of Mach 4 (except when put into a ballistic flight path into the ground, where it could exceed Mach 5), the AIM-54 had the speed and the range required to close with an airborne Habu, and thanks to its onboard radar seeker, it would be tougher to shake than the Eagle’s Sparrows.

However, there remains some debate about whether or not even the Phoenix could have found its mark in the Blackbird’s high-altitude domain.

“Another factor in our favor was the small guidance fins on their missiles,” Graham wrote. “They are optimized in size for guiding a missile to its target in the thicker air from the ground up and around forty thousand feet. At eighty thousand feet the air is so thin that full deflection of the missile’s guidance fins can barely turn it.”

Related: The best fighters America *almost* put on aircraft carriers

Tomcats, Eagles, and Habus… Oh my!

At the end of the day, the Tomcat Chase and Eagle Bait sorties flown throughout the late 1970s and into the 1980s were about far more than the pilots’ pride. These exercises were about identifying technical limits (like the Eagle’s speed gate), assessing aircraft capabilities in circumstances outside the norm, and helping pilots gain the experience they need to exercise complex problem-solving in the heat of a high-stakes situation.

These exercises, like a great deal of military training, weren’t about finding winners and losers, they were about making everyone involved, from the ground crews, to command and control, to the pilots better at some of the most difficult, arduous, and complex jobs in warfare.

But that doesn’t mean fighter pilots didn’t take their chance to down a Habu seriously… and as you might expect, they took losing just as seriously.

“There was some animosity at first with both the Eagles and the Tomcats because they kept accusing us of not showing up,” Peters recalled about the times the fighters couldn’t find his fast-moving Blackbird. Listening in on the open radio lines, Peters couldn’t help but enjoy their frustration a bit. “They got a little huffy because nobody told them we weren’t coming.”

Read more from Sandboxx News

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower

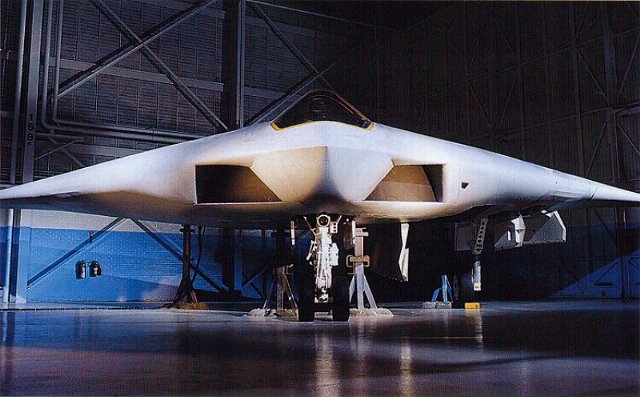

The A-12 Avenger II would’ve been America’s first real ‘stealth fighter’

Why media coverage of the F-35 repeatedly misses the mark

It took more than stealth to make the F-117 Nighthawk a combat legend

B-2 strikes in Yemen were a 30,000-pound warning to Iran

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page