How does China’s new J-35 stealth fighter compare to America’s F-35?

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Last week, China officially unveiled its second domestically developed 5th-generation fighter, known officially as the J-35. This new twin-engine stealth fighter, which comes in both runway and carrier-capable variants, is meant to not only bolster China’s rapidly expanding fleets of J-20 stealth fighters, but to also end America’s global monopoly on exporting stealth aircraft.

The J-35 was developed out of the Shenyang FC-31 program, which made its public flying debut almost 10 years ago. Combined with the forthcoming catapult-equipped Class 003 supercarrier that’s currently undergoing sea trials, this new fighter could provide China with a massive boost in power projection; it will also significantly complicate America’s combat calculus regarding deterring Chinese aggression in the South China Sea and beyond.

Yet, before the J-35 can shift the balance of power over the Pacific, it’ll have to prove that it can do more than just look the part of an advanced stealth fighter.

The J-35’s origins

In late 2002, China’s air force announced its intentions to develop and field a new stealth fighter in a similar vein to America’s class-leading F-22 Raptor which was still working its way toward service at the time. This effort, initially dubbed simply J-X and later changed to J-XX, ultimately resulted in a contract award to the Chengdu Aerospace Corporation for their Project 718 design in 2008, that would ultimately mature into today’s operational fleet of J-20 Mighty Dragons.

Despite failing to secure a formal nod from the PRC, competing firm Shenyang Aircraft Corporation decided to press on with its stealth fighter design, with the intended goal of competing with the new American-led F-35 as the world’s only other stealth fighter on the export market. This effort would ultimately continue under several different designations and was finally unveiled officially in November 2012 as the Shenyang FC-31, using the common Chinese export fighter prefix of “FC.” According to Shenyang, the aircraft made its first flight at around this time, though public available details remain sparse.

In 2014, the FC-31 made its public flying debut at an airshow in China, powered by a pair of Russian-sourced RD-93 turbofan engines similar to those found in the Soviet MiG-29. However, its performance left a great deal to be desired. As aviation journalist Reuben Johnson reported from the event, China’s new stealth fighter – even without carrying anything close to the weight it would in a combat scenario – appeared sluggish and incapable, with the pilot seemingly struggling to keep its nose up during hard turns and being forced to lean into the afterburners more often than other similar fighters in order to maintain a maneuvering energy state.

In December 2016, Shenyang’s second FC-31 prototype took to the sky for the first time, sporting several improvements over its predecessor led by a pair of Chinese-sourced WS-13E turbofan engines in place of the dated Russian RD-93s. These new Chinese-sourced engines were effectively improved copies of the RD-93, and offered a minor but respectable boost in power output to the tune of a roughly 13 percent increase under military power and around a six percent boost in power under afterburner. While these smokeless turbofans did improve maintenance requirements and likely had at least some beneficial impact on stealth, they remain engines designed and intended for 4th generation, or non-stealth, fighter applications.

The rest of the aircraft saw similar iterative improvements, with slight changes made to nearly every surface and structure from the cockpit canopy to the vertical tail surfaces all aimed at improving the fighter’s stealth and aerobatic capabilities. This design overhaul that took place between 2014 and 2016 closely aligns with a similar overhaul of China’s premiere stealth fighter, the Chengdu J-20, which also saw significant improvements between its second prototype in 2012 and its third in 2014.

Related: Stolen stealth fighter: Why China’s J-20 has both US and Russian DNA

J-35’s similarities to the F-35

The above timeline is notable because, in August 2014, a Chinese national named Su Bin was indicted for the theft of over 630,000 protected documents relating to various American military aircraft programs – including the F-22 Raptor and F-35 Lightning II – dating as far back as 2008. Su Bin, who gained access to Defense contractor systems and coordinated with PLA hackers to execute the theft and prepare full reports for Chinese officials even bragging to his Chinese contacts that stolen information from the F-22 and F-35 programs would “allow us to rapidly catch up with U.S. levels … To stand easily on the giant’s shoulders.”

However, having access to documentation – and even blueprints – for America’s stealth fighters doesn’t necessarily mean you can build a copy of one. Aircraft like the F-35 represent a collaboration between countless firms tasked with designing and mass-producing an extremely long list of separate systems that ultimately need to work seamlessly together. The F-35 is not a single invention produced by Lockheed Martin, but rather an array of inventions produced by experts in countless different fields, expertly integrated into a single functional form.

So, while China was able to expedite development by drawing direct inspiration from Lockheed Martin’s stealth fighter designs, particularly when it comes to the overall radar-deflecting planform, the similarities between Chinese and American fighters remain largely skin-deep.

It wasn’t until 2020 that the Chinese government came around to funding the development of this second stealth fighter, and while the PLA only formally acknowledged that a new fighter was in the works, Chinese media rightfully assumed this new fighter would be a variant of the FC-31 meant specifically for carrier duty, likely aboard China’s newest Type 003 supercarrier.

This new fighter, dubbed J-35, would fly for the first time in October 2021, boasting heavier-duty landing gear that included dual wheels at the nose, a catapult launch bar to support launches from the new Chinese carrier (a significant shift from the ramp-launches conducted on earlier Chinese flat tops), and a sensor turret on the chin for a new electro-optical targeting system. In true carrier-fighter form, the J-35 also came with folding wings and slight fuselage changes, likely aimed at providing additional fuel storage. Yet, this new variant of the FC-31 was, as a result, quite a bit heavier than previous test articles, potentially offsetting any performance gains made by the transition to Chinese-sourced engines.

Another prototype, this time sporting upgraded WS-13X engines, would follow in 2022. These new engines, while still based on the dated RD-93 design, did come with serrated exhaust nozzles and other changes meant to offset some degree of both radar and infrared detectability. Finally, a land-based variant of the fighter, now known as the J-35A, made its first test flights in September 2023, carrying lighter landing gear and smaller wings.

Comparing the two stealth jets

Despite their conspicuously similar appearances, China’s new J-35 is intended to serve in a very different role from America’s F-35. Modern fighters are expected to be truly multi-role in their capabilities, carrying the requisite systems onboard to competently prosecute both airborne and ground-based targets, but despite this inherently broad skill set, fighter programs still tend to prioritize air-to-air or air-to-ground missions.

America’s F-35, for instance, may be a very capable air-to-air platform thanks to its extreme degrees of both low observability and powerful sensor fusion, but the jet’s design prioritizes the air-to-ground, or attack, mission set, leaving the air superiority mission to its sister fighter, the F-22 Raptor. According to Chinese media, the J-35 and J-35A are not following suit, and are instead focused on the air superiority mission. As such, the J-35 falls into a role that doesn’t currently exist within the U.S. inventory, namely that of the low end of a 5th-generation air superiority high-low mix. (“High-low mix” is a mix of high-cost high-capability systems with low-cost low-capability to complement each other so the sum is greater than the parts).

China’s in-service stealth fighter, the Chengdu J-20, was arguably designed to serve as a long-range interceptor capable of successfully engaging American fighters thanks to a high degree of frontal-aspect stealth (of stealth from head-on). The J-35, at only around 56 feet nine inches long, is a much shorter-ranged fighter, with a claimed combat radius of only around 750 miles. This shorter range is a much bigger drawback for the Chinese fighter than it is for America’s F-22 and F-35, which both offer similar ranges.

This is because China’s tanker fleet is primarily made up of some two dozen dated H-6 refuelers and a handful of Ukrainian-sourced Il-78s, with the new YY-20, which is roughly comparable to America’s KC-135’s refueling capabilities, now making its way toward service. On the other hand, the United States operates some 568 specialized refueling aircraft and can also use non-specialized platforms, like other fighters, for refueling.

Related: America’s massive military advantage nobody talks about: 500+ refueling aircraft

However, the ability to launch these new J-35s from China’s forthcoming Type 003 aircraft carrier could certainly offset some range anxiety, as it would give China the means to scramble stealth fighters from anywhere in the Pacific that’s within a few days travel of a friendly port.

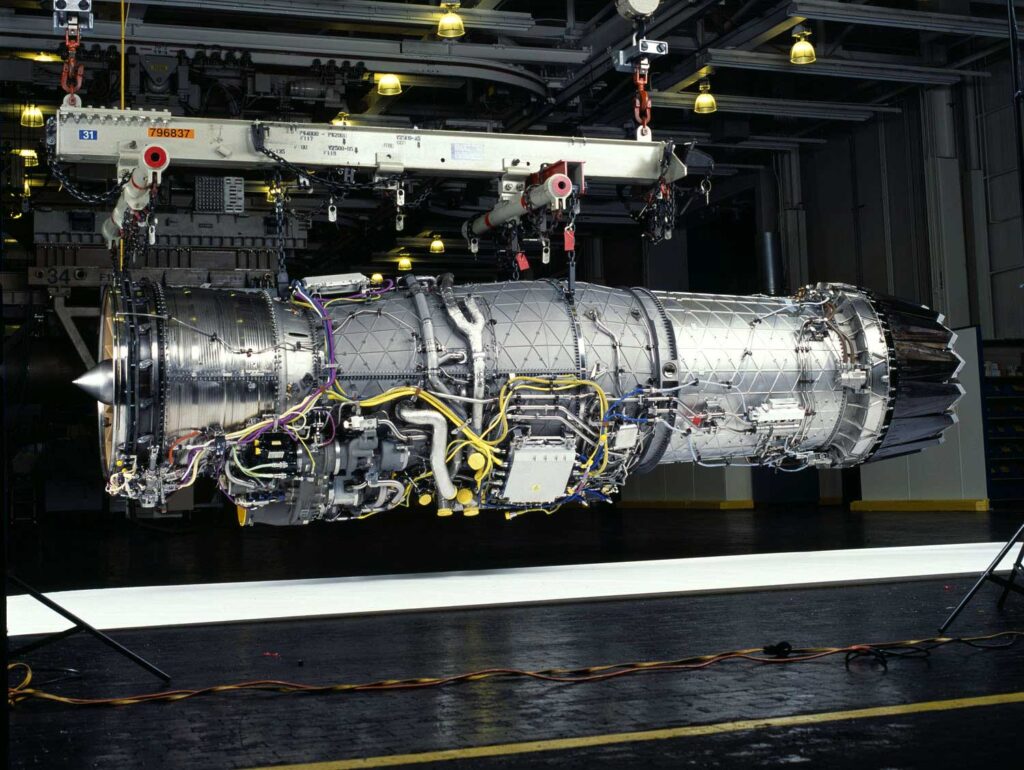

The J-35 also departs dramatically from the F-35 when it comes to propulsion, using the aforementioned pair of WS-13 turbofans in contrast to the single Pratt & Whitney F135 that powers America’s carrier-based stealth jets. Some have argued that the J-35’s use of two engines makes it more suitable for carrier operations from a safety and survivability standpoint, as it allows for the possibility of a single-engine failure without the aircraft going down. However – as turbofan engines’ reliability continued to increase – today single-engine aircraft have such low engine-mishap rates that they regularly outperform their twin-engine predecessors in terms of safety.

China’s modernized WS-13X engines, also known as WS-21s, produce a claimed 12,760 pounds of thrust under military power and 21,000 pounds of thrust under full afterburner, for a combined 25,520 pounds of thrust in normal operation and 42,000 with the afterburners engaged. That means that, despite the additional production and maintenance requirements that come with doubling the engine count, the J-35 still offers slightly less power, both with and without its afterburners, than the single F135 in America’s stealth jet.

Pratt & Whitney’s F135 builds off of the immense success of the powerful F119 designed for the F-22 Raptor. The F135 is an extremely powerful engine that outperforms previous engine designs in terms of weight, power production, reliability, fuel efficiency, heat dissipation, electrical production, and more. China’s efforts to field a similar engine for its J-20, known as the WS-15, has seen repeated setbacks with the first J-20 spotted flying with prototype WS-15s not emerging until 2023. Like the J-20, the J-35 is also meant to receive an advanced new engine – the WS-19 – which will be built using technologies matured in that WS-15 program. This indicates that China is still struggling to catch up to the propulsion technologies the United States began fielding in 1997.

Related: Why media coverage of the F-35 repeatedly misses the mark

Despite being slightly larger than the F-35, the J-35 is expected to be lighter, with a maximum takeoff weight of just below 62,000 pounds, roughly 4,000 pounds less than the F-35A. This, combined with a sleeker design, China claims, will allow the J-35 to reach maximum speeds of Mach 1.8 (slightly faster than the F-35’s Mach 1.6) while carrying four medium-range air-to-air missiles, like China’s PL-15, internally. The F-35 is likewise limited to carrying four weapons internally, at least until the Block 4 upgrade increases that limit to six.

The F-35 takes a commanding lead in terms of onboard avionics. The J-35 is expected to carry China’s latest KLJ-7A Active Electronically Scanned Array radar – which is an improvement over the original KLJ-5 found in the J-20 and has already seen service in the Block III JF-17. This array is broadly considered to be competent for air-to-air and air-to-ground operations, but can’t overcome America’s near two-decade head start in fielding AESA radar technologies. The F-35 currently carries the AN/APG-81, the most technologically advanced and powerful radar array ever affixed to a fighter; and even that system is due for replacement in the forthcoming Block IV upgrade to the AN/APG-85. As such, by the time the J-35 enters service, it will be carrying a radar array that is at least one (but arguably two or even three) generations behind the arrays found in F-35s.

Likewise, the J-35 appears to carry the same EOTS-86 electro-optical targeting system already found in the J-20. This is a competent system, but one that falls short of the F-35’s AN/AAQ-40 that works in conjunction with its distributed aperture system to allow for targeting options in any direction, rather than being limited to the frontal hemisphere as found in the J-35 and J-20.

The same can almost certainly be said for the rest of the avionics systems found inside the J-35 when compared to the more technologically advanced F-35. Despite emerging years after its American-led competition, the J-35 still reflects China’s decade-spanning effort to close the technological gap with Western powers like the U.S., and while China has made significant progress in this regard, there remains a great deal of ground to cover.

Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean the J-35 can be dismissed outright; in fact, this fighter could mean big trouble for the United States and its allies in the long run.

Feature Image: The J-35A at the Zhuhai Airshow 2024. (China News Service)

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Who dares wins: The importance of defeat in being successful

- How the military bounced back from the recruiting crisis

- These were 5 outrageous uses of nuclear power during the Cold War

- What damage can Ukraine inflict on Russia using its long-range Western weapons?

- Video: How good is China’s new stealth fighter?

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart -

A-10 ‘Warthog’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Military Affairs

How US Special Forces took on Wagner Group mercenaries in an intense 4-hour battle

F-16s carrying the A-10’s 30mm cannon actually saw combat

Why China’s new J-35 jet could mean trouble for America

Is Elon Musk right saying that fighter jets have become obsolete?

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page