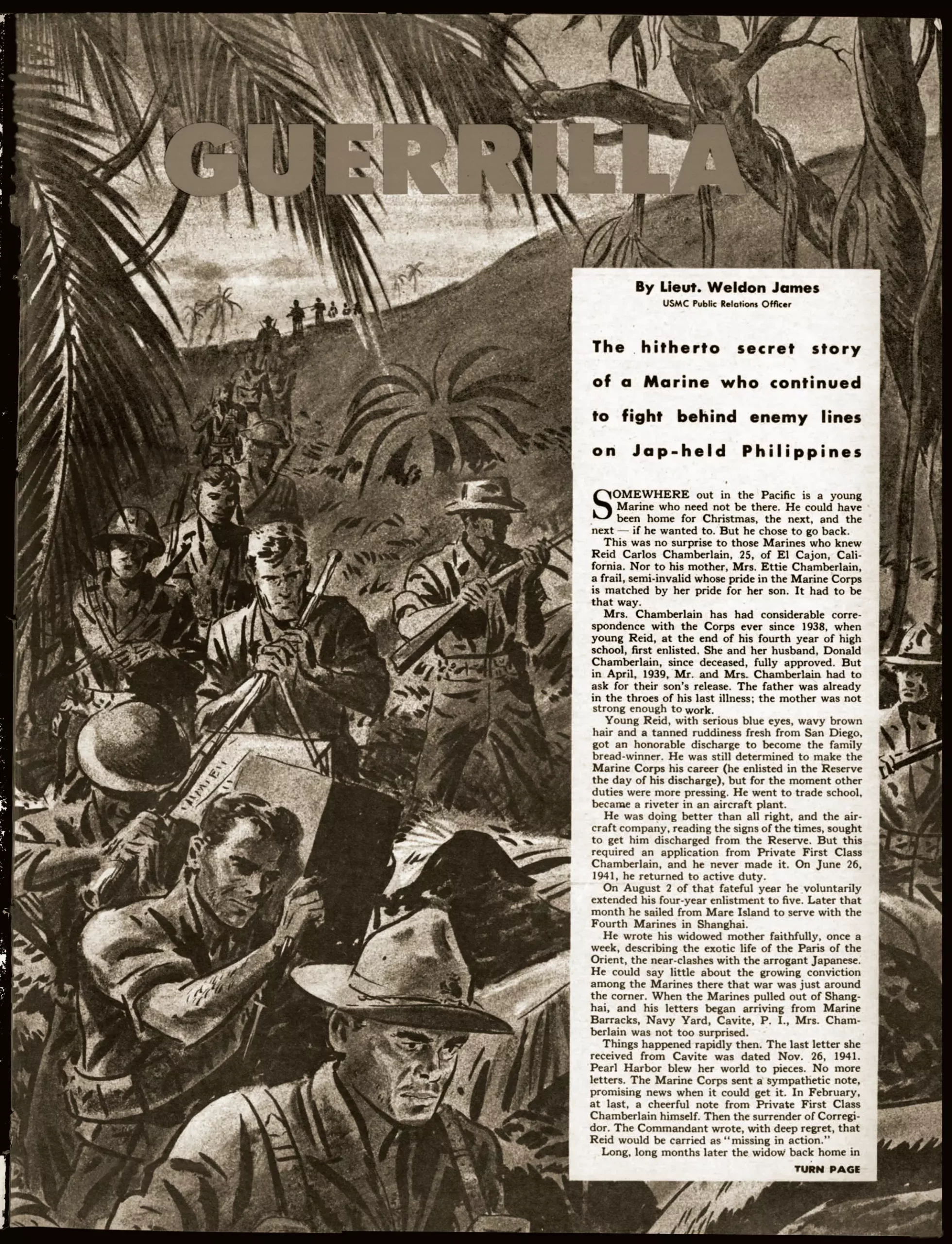

The bravery of a Marine guerrilla in World War II

- By Leatherneck Magazine

Share This Article

This article by Lt. Weldon James was originally published by Leatherneck Magazine.

Somewhere out in the Pacific is a young Marine who need not be there. He could have been home for Christmas, the next, and the next — if he wanted to. But he chose to go back.

This was no surprise to those Marines who knew Reid Carlos Chamberlain, 25, of El Cajon, California. Nor to his mother, Mrs. Ettie Chamberlain, a frail, semi-invalid whose pride in the Marine Corps is matched only by her pride for her son. It had to be that way.

Mrs. Chamberlain has had considerable correspondence with the Corps ever since 1938, when young Reid, at the end of his fourth year of high school, first enlisted. She and her husband, Donald Chamberlain, fully approved. But in April 1939, Mr. and Mrs. Chamberlain had to ask for their son’s release. The father was already in the throes of his last illness; the mother was not strong enough to work.

Young Reid, with serious blue eyes, wavy brown hair, and a tanned ruddiness fresh from San Diego, got an honorable discharge to become the family breadwinner. He was still determined to make the Marine Corps his career (he enlisted in the Reserve the day of his discharge), but for the moment, other duties were more pressing. He went to trade school and became a riveter in an aircraft plant.

He was doing better than all right, and the aircraft company, reading the signs of the times, sought to get him discharged from the Reserve. But this required an application from Private First Class Chamberlain, and he never submitted it. On June 26, 1941, he returned to active duty.

Related: Letters to Loretta: A series into the power of humanity to persevere during war

On Aug. 2 of that fateful year, he voluntarily extended his four-year enlistment to five years. Later that month he sailed from Mare Island to serve with the 4th Marines in Shanghai.

He wrote his widowed mother faithfully once a week describing the exotic life of the Paris of the Orient and the near-clashes with the arrogant Japanese. He could say little about the growing conviction among the Marines there that war was just around the corner. When the Marines pulled out of Shanghai and his letters began arriving from Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, Cavite, P.I., Mrs. Chamberlain was not too surprised.

Things happened rapidly then. The last letter she received from the Philippines was dated Nov. 26, 1941. There were no more letters after Pearl Harbor. The Marine Corps sent a sympathetic note, promising news when it could get it. In February, at last, a cheerful note from PFC Chamberlain himself. Then the surrender of Corregidor. The Commandant wrote, with deep regret, that Reid would be carried as “missing in action.”

Long, long months later, the widow back home in El Cajon got the terrible news from Headquarters Marine Corps beginning: “Deeply regret to inform you cablegram from International Red Cross Tokyo Japan reports that your son … now reported to have died in the Philippines … Your son’s splendid record in the service …. nobly gave his life in the performance of his duty.”

The grieving, ailing mother wrote back with simple eloquence:

“I am more than grateful,” she wrote to the Commandant, “for your words of comfort … I am sure he did all he could to the last … But it’s hard to believe he’s gone … yet I am sure he would rather have gone in battle than to have been a prisoner … In his last letter to me, written Feb. 4, 1942, he said he had some close calls but nothing to worry about, and he would keep pitching … I do not regret that I let him go. It was his wish. I was and am proud of him. He was fine and unassuming. I know of no better way to go than in the service of our country…”

These words were written in March 1943. How right she was in her judgment of her son’s unwillingness to be taken prisoner, Mrs. Chamberlain was not to know for long months to come. She settled Reid’s affairs and mourned his death.

Related: This bent-barrel rifle was one of Nazi Germany’s most weird weapons

Back in the Philippines, young Chamberlain was very much alive, beginning an epic series of adventures seldom equaled in the history of the Corps.

At war’s outbreak he was serving with Company C, 1st Separate Marine Battalion, on Cavite. In those first hot days, the Marines fought back with rifle fire to aid the ack-ack guns in repelling the heavy Japanese air onslaught. Three days after Pearl Harbor, Reid sustained his first injury—a cracked right ear drum due to heavy detonations while the Americans were repelling Japanese planes bombing the Navy Yard.

Then the Marines and the Sailors were pulled out of Cavite to Bataan to guard that peninsula stronghold until the armies of Wainwright and MacArthur could fight their way to that locale for their last stand.

The Japanese knew that battle plan as well as the Americans. The handful of Marines and the shipless and plane-less Sailors, rapidly converted into Marine-trained infantry battalions, had a tough and little-publicized assignment from the very beginning. The Japanese launched attack after attack from the ocean and the bay, seeking to capture Bataan before the Army could reach it in force. They were repelled and repelled again and again. It was in one of these actions that Reid was wounded. Fighting as an infantryman with Company M, 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, he stopped a Japanese machine-gun slug with his right forearm. A corpsman treated the wound, and Reid remained in action.

Eleven days later, on March 10, 1941, he was promoted to corporal.

Before Bataan fell to the Japanese, the Marines moved again, this time to Corregidor. The gallant stand there was almost finished when, on the morning of May 6, 1942, news of the impending surrender was announced.

Corporal Chamberlain was in no mood to surrender. He knew of a motor launch he could use, and, with several Marine and Army companions, he did a disappearing act beneath the very noses of the conquering Japanese.

They had to avoid Japanese shipping, Japanese planes, and Japanese land patrols. They held their breath, and they made it to a point where friendly Filipinos guided them and hid them. How they got from island to island, where and how they served with various guerrilla bands, in those last long months of 1942, still may not be told. But the familiar pattern of substantial inroads on the enemy was continued.

Related: The FGC-9 in Myanmar: 3D Guns and the future of Guerilla Warfare

Near the end of the year, they acquired a 45-foot diesel-engined launch and set out for the coast of China. Reid had heard much about the effective work of the Chinese guerrillas while serving in Shanghai and had Chinese friends. He was bent on joining the Chinese guerrillas and “working his way” up to Chungking and the American forces.

Their engine failed some 70 miles out at sea. A makeshift sail proved too small to be effective, and they drifted for 28 bitter days before landing again in the Philippines. On this heartbreaking trip there were 10 desperate men—five Filipinos and five Americans. Dodging Japanese planes and ships was a minor part of their bleak voyage. They suffered an acute shortage of water and had no food the last few days.

Weak, but not despondent, they made an unwanted Philippine shore again. The party split up to ensure greater security. Fed and cared for by friendly natives, Corporal Chamberlain regained his strength. With another American and two Filipinos he finally acquired a native sailboat and this time set sail for Australia. The corporal was still in there, pitching.

They reached another island “outside the Philippines,” and what he heard caused Chamberlain to change his mind. He bade his friends, “Godspeed.” For himself, he was going back. To date, he had been only with small, scarcely organized bands of guerrillas. Now he had word of an organization on a really large scale, and he saw genuine opportunity ahead.

The friendly inter-islanders sailed him back to the Philippines, and as promised, delivered him to a tough young colonel in the Philippine Army. The Filipino, in turn, took him to another leader, a colonel in the U.S. Army, to whom Corporal Chamberlain reported “for duty.”

Colonel “X” sized up the slender, hard-eyed young Marine then asked him a few questions. Then he gave him a “guerrilla-field” commission on the spot. It was now Second Lieutenant Reid C. Chamberlain, and he became an aide to Colonel “X.”

The colonel had a great organization—Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, Filipinos, both the famous Scouts and the ill-trained but enthusiastic and effective volunteers. The Japanese held the Philippines, but the underground was swallowing many a Japanese soldier in most mysterious fashion. Just how this organization functioned may not be told but published accounts of guerrilla warfare elsewhere in the Philippines give an idea—the ambush of Japanese patrols in the jungle, the sudden raid on ammunition dumps and supply stocks, the quiet bow-and-arrow death of any Japanese soldier who strayed too far from his garrison stronghold, the invaluable communication with MacArthur’s forces and the Navy “outside.”

One of Chamberlain’s exploits can be told. The colonel sent him “outside the Philippines” on a smuggling job. Wherever it was he went, the doughty lieutenant returned with badly needed guns, gasoline, some powder, some lead — good enough material for the behind-the-lines jungle “munitions factories” equipping those guerrillas who as yet had not captured better stuff from the Japanese.

And whatever else he did, Lieutenant Chamberlain was OK by the colonel, who advanced him to first lieutenant some eight months after his commissioning. The colonel also sent back a report that was to do young Chamberlain no harm.

Related: Nazi drone technology and the Goliath tank killer

After a full two years in the Philippines, First Lieutenant Reid C. Chamberlain, USA, finally came back to America. With him came other Army, Marine, and Navy personnel, some of whom, with the guerrillas’ aid, had escaped from Japanese prison camps. Certain members of the organization stayed on.

Army Lieutenant Chamberlain was ready to get back into the Marine Corps again. Despite several bouts of malaria, his iron-man constitution had stood him in good stead; he was again a rugged 150-pounder; the doctors said he was in reasonably good shape, and he thought he could make it.

In Washington, the paper confusion was great, but the lieutenant waded through it. The Marines gave him a necessarily tardy honorable discharge, retroactive to the day before he accepted the Army commission (Jan. 15, 1943). The Army permitted him to resign his commission and, in turn, gave him an honorable discharge.

Then the hardy youth re-enlisted in the Marine Corps. He was given immediately his old rating of corporal and appointment to the officer candidates’ class at Quantico.

First, however, Chamberlain had less vigorous business to attend to. Lieutenant General Alexander A. Vandegrift, Commandant of the Marine Corps, presented him with the Distinguished Service Cross awarded by General MacArthur for “extraordinary heroism in action,” and arranged a rare thing in the service — a 60-day furlough.

A few months earlier, the Marine Corps, on the basis of “official and reliable” information, had been able to reveal to Mrs. Chamberlain that her son was indeed alive, but had to enjoin her to joyous secrecy. Not even the insurance company could be told until Reid’s actual arrival home!

Sixty days with his mother and old friends in El Cajon were not enough, Corporal Chamberlain found, to adjust himself to the bright new world of America after his dark two years abroad. He went to Quantico and had spent only four days at that rigorous, fast-moving school when he applied for transfer.

The corporal thought that if he could serve at San Diego and see more of his family and friends for “a few months,” he might complete his adjustment.

It was an unusual request, but no more unusual than the corporal. His commanding officer, noting that Corporal Chamberlain was “extremely anxious for combat duty,” approved. And it turned out that an old friend from Bataan, Colonel (now Brigadier General) W.T. Clement, was the commandant of Marine Corps Schools, Quantico. Colonel Clement “strongly recommended” that the corporal’s request be granted.

Without prejudice to his record, Corporal Chamberlain was discharged from candidates’ class. He got his transfer to Base Guard Company, MCB, San Diego. His orders stipulated he could not be transferred again without the express approval of Marine Corps Headquarters. He had a good stateside job. He was “stuck for the duration.”

It was March 22, 1944, when he left Quantico for San Diego. Soon, by direction of the Secretary of the Navy, he was presented the Purple Heart with Gold Star for those wounds of 1942. (The Marine Corps had already ruled that his mother could keep the Purple Heart sent to her after the official announcement of his “death.”)

By his own terms, the corporal had before him several months for “readjustment.” But two weeks of his safe job in San Diego were enough. On April 14, he wrote to the Commandant: “I respectfully request that I be assigned to duty in a combat area … ”

The corporal insisted that his malaria had been quiet for a long time. His commanding officer, approving, wrote that the Californian, among other assets, had “a valuable temperament for combat.”

General Vandegrift agreed. Chamberlain, by this time a sergeant of two weeks’ standing, was on his way to fight the Japanese again.

Mrs. Chamberlain wasn’t surprised. She’d known all along it’d have to be that way.

Sgt Reid C. Chamberlain was killed in action on Iwo Jima on March 1, 1945, only two months after this article was originally published in Leatherneck. His remains are listed as unaccounted for.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The Marines want to make their secret beach-swarming drones autonomous

- This bent-barrel rifle was one of Nazi Germany’s most weird weapons

- A Russian soldier’s newly translated account of the war in Ukraine reveals the poor state of Russia’s military

- This is how you can join the Ukraine Foreign Legion (and who can join it)

- “Age of Empires 2: Definitive Edition” can teach valuable skills to service members

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

Leatherneck Magazine

Related to: Breaking News, Military History

Space Force to deploy new jammers to yell at enemy satellites

Congress demands answers on low testosterone issues among special operators

Video: US military sends aircraft to help with LA fires

Video: DARPA wants to arms a missile with cannons

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page