From cargo plane to gunship: The evolution of the C-130

- By Coffee or Die

Share This Article

This article by Matt Fratus was originally published by Coffee or Die.

The C-130 has an impressive resume of preposterous accomplishments with few limitations, post-modification. Need to land a massive cargo plane in a football stadium or on an aircraft carrier? No problem. Have an issue with a landing gear in the arctic and need to swap for snow skis with a rocket boost? No big deal. Have a special operation where the troops on the ground require aerial superiority with coverage overhead from the biggest weapon ever mounted on a combat aircraft? Send it.

The evolution of one of the most versatile aerial platforms in modern history came, as the majority of military technological advancements do, at a time of war. When the U.S. Air Force entered the Korean War they had recognized gross limitations in their airlift operations. In collaboration with Lockheed Martin, the U.S. Air Force Tactical Air Command produced two prototype YC-130 aircraft with the capabilities of conducting medium-range airlift missions in remote and austere environments.

The proposal of the YC-130 was a risk because investing in a turbo-prop aircraft in the height of the jet-age could have tarnished Lockheed Martin’s reputation if the project had failed. To the astonishment of even the engineers, the C-130 has exceeded all expectations tenfold. Ater a successful test flight on August 23, 1954, its four turboprop engines, each with 3,750 horsepower — built to transport 64 paratroopers (72 soldiers total) — surpassed every requirement of the Air Force for a newly refined cargo plane. Since then, over 40 variants of the aircraft have sailed through the skies in support of scientific research, weather reconnaissance, humanitarian airlift missions, combat operations, aerial refueling, and wildfire suppressant.

Hurricane Hunters

The Hurricane Hunters were born smack dab in the middle of the U.S. involvement in World War II, and its origins began with a dare. When several British pilots — many of whom achieved the glory of calling themselves “Aces” — were filling the ears of flight instructor Lieutenant Colonel Joe Duckworth with sarcastic remarks of encouragement of his “inferior” flight instruments, he challenged them to a friendly wager. If he could fly an AT-6 “Texan” Trainer into and out of the eye of a hurricane as it came ashore in Gavelston, then they’d have to respect both his aircraft and his instrumental flying technique.

On July 23, 1943, he and his navigator, Lieutenant Ralph O’Hair, against the rules set forth by his command, flew through the turbulent storm. The winds and rain were so severe that he said it was like “being tossed about like a stick in a dog’s mouth.” When they returned to base, another curious weather officer, Lieutenant William Jones-Burdick, demanded to take flight into the storm’s epicenter to see for his own two eyes. From that point onward, Bryan’s Field became the capital of “instrument flying” and the pinnacle of weather reconnaissance test flights.

Throughout the years, aircraft were technologically advanced and outfitted with improved instruments. The B-17 Flying Fortress and the WB-25 Mitchell flew missions throughout the 1940s. The U.S. Army created the “Army Hurricane Reconnaissance Unit” in 1944, the earliest predecessor of today’s Hurricane Hunters. It was only natural that the WC-130 would join the mix by 1963 and their famous reputation of dependability has been with the unit ever since. The WC-130 is said to be one of the most reliable aircraft in weather aviation history, an accomplishment that remains consistent in many of the platforms’ variants.

The Antarctic Program

Described as “the backbone of U.S. transportation in Antarctica,” the LC-130 Hercules burst onto the scene in 1960. An unforgiving environment such as the arctic, with conditions that change in a moment’s notice, calls for a specific aircraft. Sometimes referred to as the “Snowbird,” this modified cargo plane utilizes a ski-equipped landing gear, which prevents uncontrolled sliding on snowy or icy surfaces. When the Snowbird has to land on harder surfaces, the landing gear can be exchanged for a traditional wheel.

In support of the National Science Foundation’s mission, the Snowbird transports groups of scientists and supplies from McMurdo Station — the largest Antarctic station claimed as a territory by New Zealand — to the South Pole for scientific research. A one-way trip is 728 miles, but the Snowbird has the fuel capacity to make it without refueling.

How does the Snowbird get enough umph to be able to lift off from a makeshift airstrip composed of shelf ice? Engineers equipped rockets on the rear to assist with thrust and counter drag and called it JATO (Jet-Assisted-Take-Off). Experiments with rocket-powered aircraft originated around World War II when Ernst Heinrich Heinkel, a German aeronautical engineer, developed them for military aircraft. The JATO system isn’t often used in real-world practicalities, but the Blue Angels’ “Fat Albert” certainly entertains spectators at air shows.

The National Science Foundation also uses the NCAR-130 for scientific research at high altitudes. The payload carries a variety of instruments that measure turbulence, icing properties of clouds, and collects samples from emissions of the oceans and parts of the atmosphere.

It did what?

In October and November of 1963 the KC-130F became the largest and heaviest aircraft to ever successfully land on an aircraft carrier. The 85,000 pound behemoth needed to come to a complete stop in only 267 feet on the flight deck of the USS Forrestal without the use of a catapult or an arrestor. Lockheed Martin had a few minor modifications to pull off the feat, including a “smaller nose-landing gear orifice, an improved anti-skid braking system, and removal of the underwing refueling pods.”

Art E. Flock, Lockheed Martin’s chief engineer, was aboard the USS Forrestal to witness one of the 21 unarrested full-stop landings. “That airplane stopped right opposite the captain’s bridge,” recalled Flock, who was standing perpendicular to the airship. “There was cheering and laughing. There, on the side of the fuselage, a big sign had been painted on that said, ‘LOOK MA, NO HOOK.’” Remarkably, these pilots had zero prior experience flying a four-engined aircraft, and they were able to successfully complete 29 more touch-and-go landings and take offs. During which, they gradually increased the payload to reach a maximum of 30,000 pounds.

Related: The Navy’s plan to fly the C-130 off aircraft carriers (that worked)

The tests yielded results that showed the C-130 needed only 745 feet to take off and 460 feet to land. Lieutenant James H. Flatley III, one of the pilots, received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his participation.

AC-130 Gunship & Operation Commando Vault

The Attack Cargo-130 gunship (AC-130 gunship), famously referred to by its call sign “Super Spook,” replaced Douglas AC-47 Spooky and flew its first combat mission on Sept. 27, 1967, in Nha Trang, Republic of Vietnam. The following year saw the emergence of the AC-130A Spectre gunship, which supported U.S> Army Special Forces soldiers on the ground with armed reconnaissance and close air support. Different adaptations of the gunship continued to provide valuable advancements in capabilities, and by 1969, the AC-130A had Gatling guns with an analog fire control system mounted on the left side of the airframe. The Surprise Package upgraded its weapons systems and employed 20mm rotary autocannons and 40mm Bofors cannons.

Its presence in the airspace gained a mythical reputation — it soon was called “Puff the Magic Dragon” in reference to its explosive firepower. The AC-130E was next in line and introduced an active TV system and the 105mm cannon that aided in its fearsome control of the battle space.

Related: B-1B Gunship: Boeing’s plan to run big guns on the Lancer

When the C-130 wasn’t turning manmade inventions into scrap metal, it was dropping bombs that turned trees into splinters. These missions fell under the plan Operation Commando Vault, which called for C-130s to carry and deploy BLU-82/B (Big Blue 82) bombs into dense vegetation that wiped out sections of forests. These bombs were sometimes referred to as “Daisy Cutters,” a nickname referring to their ability to clear large landing zones for Huey helicopters.

The process in which they were deployed wasn’t simply “rolled out of the back” as has been suggested by some reports. Rather, the 15,000 bombs were released on the activation of a handle. The bombs’ extraction parachute deployed and helped the bomb drift to its target before it exploded with a large concussive shockwave. The U.S. Air Force used them in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, and they were ultimately redeployed in Desert Storm as tools in psychological warfare in Kuwait.

For the past 50 years, the AC-130 gunship has participated in support of special operations in conflicts and wars including Operation Urgent Fury (Grenada), Operation Just Cause (Panama), Operation Restore Hope (Somalia), Operation Deliberate Force (Bosnia), and present day operations within the Global War on Terrorism. It remains one of the most durable, devastating, and fearsome aircraft in U.S. military history.

Operation Credible Sport, 1980

When a helicopter collided with a C-130 on an airfield during Operation Eagle Claw killing everyone onboard, a second rescue attempt was put into motion in response to the Iranian Hostage Crisis. A top-secret program at Eglin Air Force Base had developed the “super STOL” — a tricked-out C-130 with a reinforced airframe and strategically placed rocket mortars affixed to its fuselage for control in take offs and landings.

In similar fashion to the LC-130 Snowbird and its application of JATO rockets coupled with the capability of landing on an aircraft carrier, the U.S. military believed the C-130 was the perfect platform for Operation Credible Sport. The task: landing the 80-ton plane on a 350-foot Iranian soccer stadium. Considering average C-130 needs a runway that is 855 feet in length while most aircraft require a 5,000-foot runway, this Hercules needed some special gadgets to pull off such a daring feat.

Initially, 58 JATO rockets were selected, but training attempts showed that they added too much weight. In total, 28 rockets assisted the C-130 in its descent and added a propulsion capability during its takeoff. Every test was a success, but disaster struck on its final attempt when the plane was 20 feet off the tarmac. Faulty calibration with the rockets had failed and caused the plane to lose lift and smash into the runway. It was engulfed in flames, but no one was injured. The risk was too high to move forward, and the operation was canceled.

The Forest Service debacle

The C-130 exchange program between the Department of Defense and the U.S. Forest Service was filled with controversy, scandals involving the CIA, and crime and corruption later revealed in congressional investigations that have ramifications to this day. The Forest Service acquired 28 to 35 surplus military aircraft —with a value between $67 million and $80 million — for pennies ($15,000 each) in a lopsided trade in 1989. The intention for the fleet of planes was to transform them into air tankers to fight forest fires in the Pacific Northwest. Instead, contractors of the Forest Service illegally used a number of C-130 aircraft to transport cargo around the globe for private companies and covert military operations.

Some were stripped of their parts and sold for cash, with one businessman pocketing $1.1 million. Others disappeared until they would randomly resurface in airfields in Kuwait as they were suspected of being owned by the CIA . The relationship between the two unlikely partners has a rich history, including the use of smokejumpers in the Vietnam War who acted as “kickers” or loadmasters who dropped emergency resupplies for soldiers in remote parts of Laos. The records for the mystery Forest Service planes disappeared, and the paper trail of their involvement in these projects evaporated.

Gary Eitel, a former Vietnam War helicopter pilot and CIA contractor, was the whistleblower for these secret spying programs. “You look at them, and you think they are firefighting planes. But they are really little AWACs,” Eitel said in an interview with the Associated Press in 1996. “You could fly into foreign countries and hear what pilots are saying to each other, eavesdrop on embassies; you can jam a national communications system with it.”

He testified before Congress in the 1990s after he discovered C-130’s from Australia were about to be transferred from the private sector to South America where they would vanish into the shadowy world of drug smuggling.

Although the scandal is a dark cloud over the C-130’s wildfire fighting history, these aircraft have participated in wildfire suppression missions since 1974. They use the Modular Airborne Fire Fighting System (MAFFS), which gives these water bombers the capacity to hold 3,960 gallons of water or fire retardant. They are an aerial asset to wildland firefighters on the ground.

Read more from Sandboxx News:

- Could we really build a B-1B Gunship?

- How an F-15E shot down an Iraqi gunship with a bomb

- America could have had this flying tank instead of the Apache

- The best prequel ‘Star Wars’ vehicles for each military branch

- These are the aircraft used by the Army’s Night Stalkers

Feature image: USCG Photo/ Dave Silva

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Coffee or Die

Coffee or Die Magazine is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online news and lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers stories both about and for the military, first responder, veteran, and coffee enthusiast communities.

Related to: Airpower

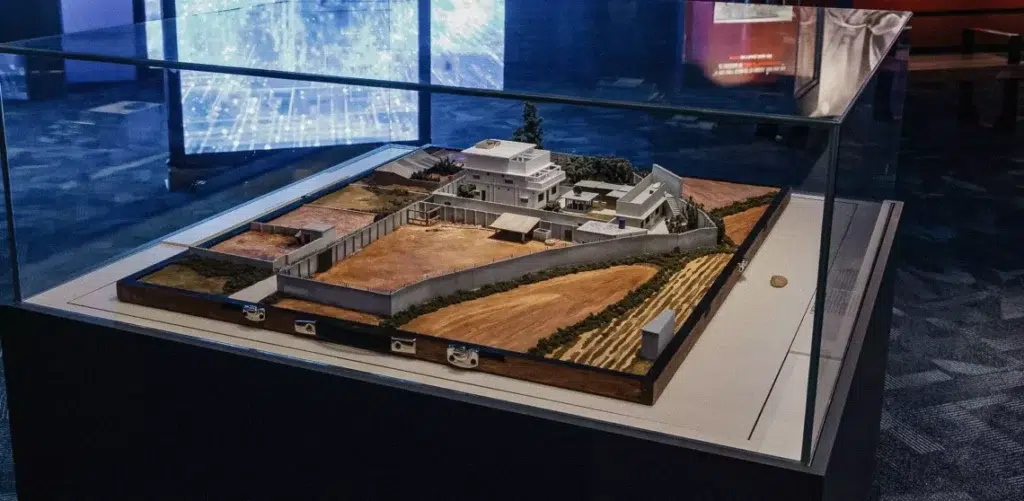

The CIA used miniature models to meticulously plan high-stakes operations

Marines deploy new system to take out ships in the Pacific

British intelligence once hacked al-Qaeda just to mess with them

The Space Force wants its own boot camp

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page