FIGHTER PILOTS HAVE TO CONSERVE MENTAL ENERGY LIKE JET FUEL. HERE’S HOW

- By Hasard Lee

Share This Article

One of the sayings we have in the fighter community is that as soon as you put on your helmet, you lose 20 IQ points. A modern fighter pushes what the body and mind can handle to the limit. Tactics that look easy on the ground become difficult once you’re in the air under G with 30,000 pounds of thrust coming out of your jet.

In Afghanistan, after eight-hour night missions, I would come back feeling like I ran a marathon while taking the SAT. We were the only fighter squadron in the country when Secretary of Defense James Mattis took over and declared that he wanted ISIS annihilated. Immediately, our ops tempo spiked. Because we flew so quickly, we were able to have a strategic impact on the battlefield. One hour we would be supporting a mission in Southwestern Afghanistan, then next we would be flying Close Air Support for troops under fire on the other side of the country. There were nights when we would tank six times while supporting just as many engagements. The experience taught me that you have to treat your mental energy just like the fuel you’re carrying.

A fighter, more so than nearly any other machine, has the ability to operate throughout a wide range of regimes. If we’re maximizing endurance, we have the ability to stay airborne for hours without refueling. If we’re prioritizing speed, in max-afterburner, we can burn all our fuel in under 10 minutes. It’s ingrained in us to always be cognizant of our power setting and how it’s relating to our overall mission success.

It only took me a few flights in the F-16 to understand the importance of fuel management, but it took me nearly six years to really understand the importance of managing my mental energy. Just like I couldn’t leave the throttle in afterburner the whole flight, I realized I couldn’t stay 100% focused for eight hours straight.

Our typical training flights last only about an hour and a half. Tankers can be difficult to come by so we’re limited by the fuel we can carry. Occasionally, we’ll do a mid-mission tank which can double our flight time, but it’s nowhere close to eight hours.

My first flight in Afghanistan I came out like a sprinter in a marathon. After a few hours, I could sense my judgment was not as crisp as when I took off. By the time I came back to land, I could feel the fatigue setting in, which is not a great place to be when you’re in a single-seat aircraft, in the weather, at night, with 15,000 foot mountains surrounding you.

Over the next few months, I developed a routine. Every 10 minutes or so I would take a deep breath and a sip of water. Every half-hour I would eat part of a peanut-butter pack. When I went to and from the tanker I would focus on my breath for a few moments. These seemingly small changes allowed me to pace myself and not burn through my mental energy too quickly. They allowed me to have a reserve that I could call on for important situations. Overall, they made me a much more effective fighter pilot.

When I came back from the deployment, I started applying the principle to my life outside the cockpit. One of the best techniques I learned was from the great Chad Hennings—former A-10 pilot, turned NFL player, turned three time Super Bowl Champion. He practices what he calls his 5×5. Five times throughout the day he’ll silence his devices and just sit quietly to recharge his mind. I’ve used this technique for several years and it helps me to regulate my mental energy throughout the day, giving me a better view of the big picture. It prevents me from getting sucked into the various daily fires and burning mental energy that could be used for something more important.

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Hasard Lee

Related to: Airpower

How a Delta Force operator celebrated New Year’s in Bosnia

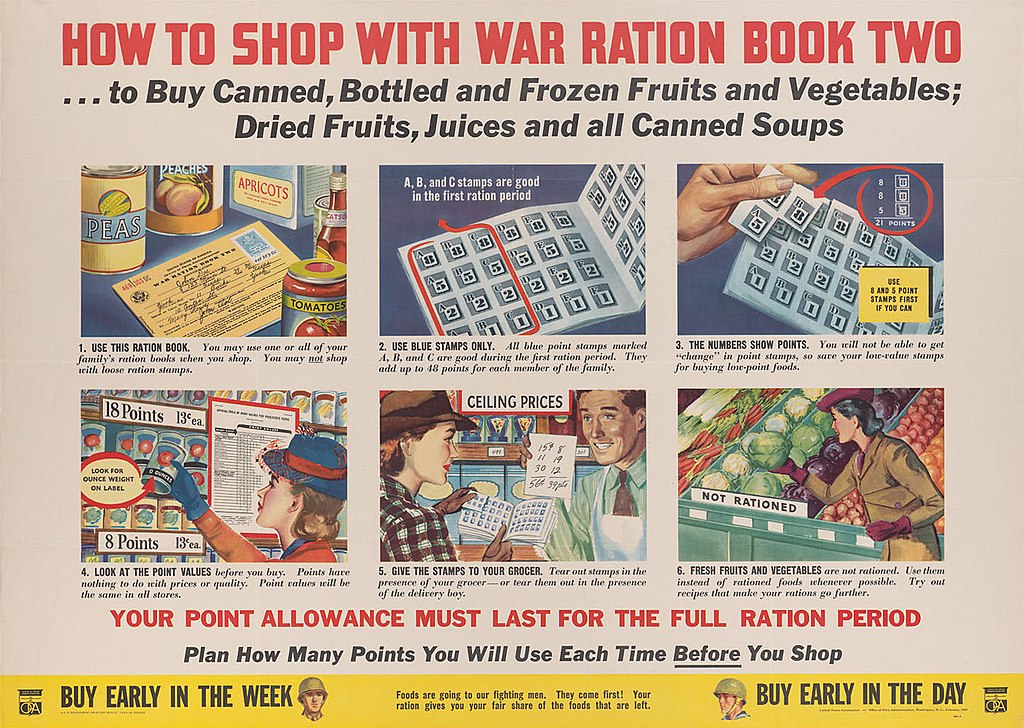

How have American military rations evolved in the last century

New Navy video imagines high-tech warfare in 2043

Russia’s Su-57 Felon will never be the F-35 fighter

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page