Everything you need to know about America’s struggle to replace its aging ICBM arsenal

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

The program to replace America’s aging nuclear ICBM arsenal, known as the LGM-35A Sentinel, is already projected to go at least 81 percent over budget, which represents tens of billions of dollars in anticipated cost overruns. Yet, despite the program’s ballooning expenses, the Pentagon has reaffirmed its commitment to the effort, calling its continuation, “essential to national security.”

To many outside of the Defense apparatus, the Sentinel ICBM program may seem unnecessary. After all, the United States already maintains a standing arsenal of more than 400 nuclear-armed Minuteman III ICBMs, each of which can deliver its nuclear payload to targets more than 8,000 miles away, traveling at speeds over Mach 23. These weapons lay in wait, housed in hardened underground silos spanning Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota, and represent only the land-based portion of America’s traditional nuclear triad.

A bevy of nuclear gravity bombs, spanning in yield from as low as 0.3 kilotons to as high as 1.2 megatons, serve alongside long-range air-launched nuclear cruise missiles as the airborne leg of the triad, delivered via a laundry list of bombers and fighters. And then, most importantly, a fleet of 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, each carrying 20 Trident II submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with multiple warheads onboard, serve as the at-sea leg of the triad while also representing the majority of America’s deployed nuclear arsenal.

The land-based Minuteman III fleet is often seen as the least important facet of America’s deterrent nuclear posture, with many experts and analysts dismissing these weapons and their hardened silos as little more than a “warhead sponge,” meant to give adversary nations such a long and daunting list of targets for any potential first strike that there will have little hope of blunting the edge of America’s nuclear response. But while this might make these ICBMs seem less important than the Navy’s deployed SLBMs, for instance, the truth is, using these isolated facilities as a “warhead sponge” might make all the difference in a nuclear conflict.

The known and permanent locations of these ICBM silos give enemy nations a list of hundreds of targets to focus on, allowing America’s missile subs and nuclear-capable aircraft to retaliate with less interference.

In other words, with hundreds of nuclear ICBMs lying in wait beneath the grasslands of the Great Plains, adversaries planning a nuclear first strike must address the looming threat of these missiles, which are dispersed and sufficiently hardened to nearly require a direct nuclear strike on each to eliminate the possibility of Minuteman III retaliation.

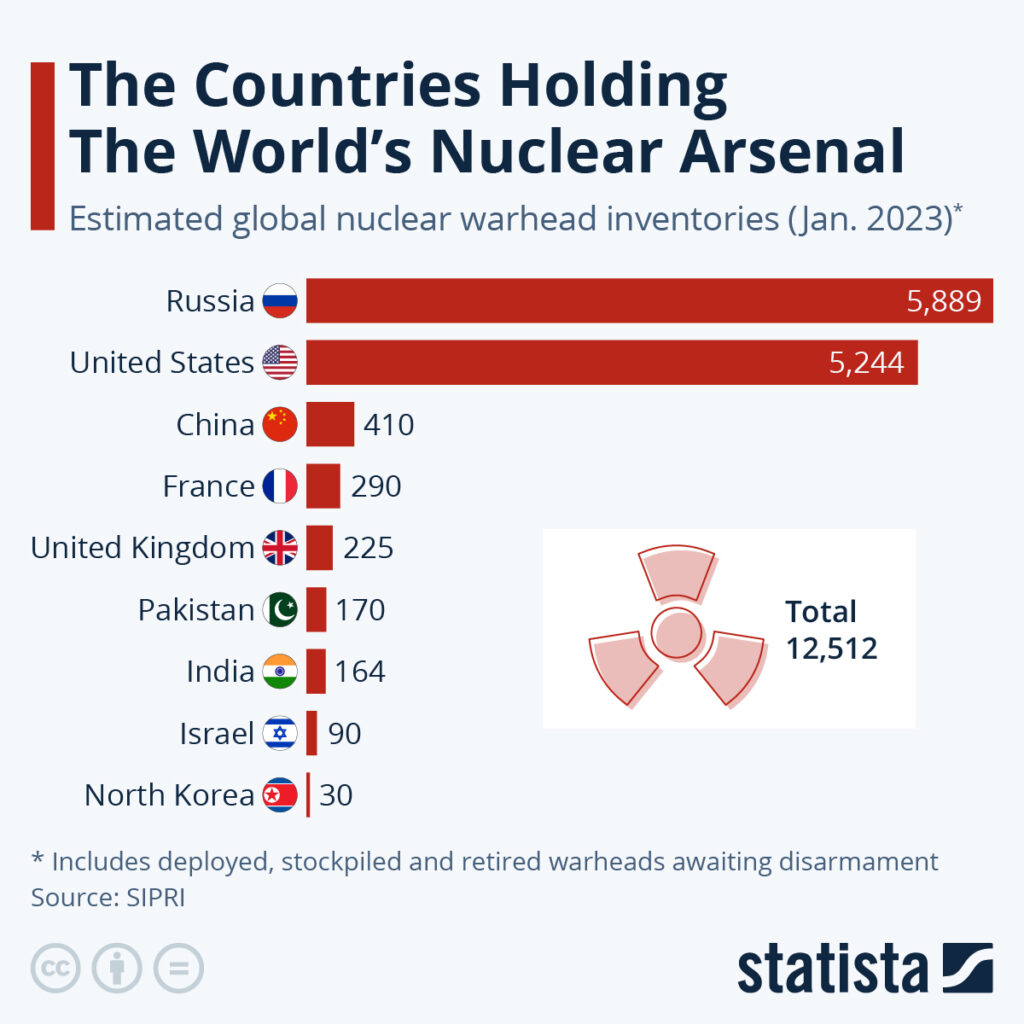

Even for Russia, which maintains the largest nuclear stockpile in the world and claims to have some 1,710 deployed warheads at any given time, this would be a serious challenge. If you assumed a broadly unlikely 100 percent hit rate, using just one Russian warhead for each of America’s known 450 Minuteman III silos, nerfing America’s ICBM fields alone would require more than a quarter of the nation’s entire deployed nuclear arsenal. If Russia opted to play it safe and devote two warheads to each silo, it would dramatically increase its chances of success, but at the expense of more than half of its deployed nuclear arms. This, of course, also means no other nation on the planet besides Russia has the warheads and the means to mount an effective attack against America’s ICBM fields.

China’s nuclear stockpile is growing faster than any other nation’s in the world, but its entire arsenal currently amounts to just 500 or so warheads, meaning it could feasibly require every nuclear weapon in China’s inventory – not just the ones deployed – to have the same effect.

Related: These are the US aircraft qualified to carry nuclear weapons

It might be easier to think of the importance of the Minuteman III as a guard standing his post with his rifle up at the alert. Adversaries know there are other guards hidden throughout the landscape and the known location of that rifleman might make him an obvious target, but attackers still have to deal with him first if they intend to mount a successful assault.

“The land leg’s geographic dispersal creates targeting problems for our adversaries, and our missileers sitting in an alert posture 24/7 ensures responsiveness,” explained Air Force Vice Chief of Staff General James Slife on July 8th.

It’s a cynical and deeply depressing way to see this swath of the American midwest – with these remote, but populated communities carrying that target on their backs for the sake of the rest of the nation. Yet, that’s the inherent and objectively cold-blooded math of nuclear warfare: It’s a game that ultimately, has no winners; only survivors.

And it’s in the interest of continuing this nuclear game of chicken that the Air Force is now forced to swallow the now-projected $140.9 billion cost of replacing those “warhead sponge” Minuteman IIIs, as the ballistic missiles Uncle Sam has long kept tucked beneath the northern Great Plains are rapidly aging into what the Pentagon considers to be an unsafe and strategically neutered obsolescence.

This is a problem the Pentagon saw coming. The Minuteman III program began in the early 1960s, with the first operational missiles entering service in 1970 before microwave ovens were common in American kitchens. At the time, the projected service life of these weapons was just 10 years, meaning the Minuteman III arsenal was slated to be replaced starting in 1980.

Since then, the branch has invested billions of dollars into not just maintaining these weapons but updating them to remain viable in a rapidly changing technological world. After all, these missiles and their launch facilities were designed and built before personal computers, VCRs or portable tape players had been invented. In fact, it wasn’t until 2019 that the Air Force finally migrated away from using eight-inch floppy disks (from the 1970s) to operate the Strategic Automated Command and Control System, or SACCS, that’s responsible for launch functionality.

The dated electronics found throughout the Minuteman III weapon and support infrastructure create significant concerns about cybersecurity – a defensive realm that simply didn’t exist when the weapon was being designed. Likewise, despite limited updates and upgrades over the years, the Air Force has been clear that the Minuteman III’s intercept countermeasures, or classified systems carried onboard meant to hinder an enemy’s ability to shoot the missiles down before they reach their targets, are aging out of relevance, presenting the real possibility that the longstanding nuclear deterrent philosophy of mutually assured destruction may no longer be quite so mutually assured.

More pressing than concerns about hacking, or the unrealistic idea that an adversary state could intercept hundreds of inbound warheads simultaneously, are the continuously reduced reliability of aging systems and components that are now so old that there’s no vendor, contractor, or commercial entity that can support, repair, or replace them – at least, not without a prohibitively high price tag.

To put it into simpler terms, the Minuteman III is the nuclear equivalent of a 1969 Dodge Charger. Its iconic design and powerful legacy are still enough to leave many in awe, but nobody in their right mind would want to race in the thing today. Upgrading the Charger to make it safe and competitive on the modern race track is certainly possible with enough money and willpower, but there’s no denying that it would be a whole lot cheaper (and easier) to just buy a modern race car.

And that’s exactly what the Air Force determined in 2014 when it conducted what the Congressional Research Service describes as a “comprehensive analysis of alternatives” to the Minuteman III, ultimately assessing that replacing these aging weapons with new, more modern ones would reduce life cycle costs while also ensuring America’s ICBMs are technologically capable of outpacing emerging threats.

Of course, there are always two sides to a debate, and others have argued that continued service life extension programs (SLEPs) on the Minuteman III arsenal, replacing aging components with more modern ones and eventually producing the ballistic missile equivalent of the Ship of Theseus, might actually be the more cost-effective solution.

That was the position taken by a group of analysts at the Rand Corporation in 2014 who were tasked with assessing possible alternatives to a new ICBM program (then known as the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent program). While the Air Force’s 2014 analysis concluded that modernizing the Minuteman III would cost just as much as replacing them, the Rand study presciently argued that a replacement ballistic missile system “will likely cost almost twice (and perhaps even three times) as much as incremental modernization and sustainment of the MM III system.”

Yet, even the Rand analysis left the door open for replacement to be the logical conclusion based on three potential factors. These were, firstly, if the Air Force felt the pressing strategic need to increase the capability of these weapons, which wouldn’t be cost-effective using the old missiles as a basis. Secondly, if the threat environment outside the U.S. changed in such a way that demanded it – such as emerging missile defense capabilities reducing the likelihood of success for Minuteman III strikes. Thirdly, and most pressingly, if the number of Minuteman III missiles the United States had left to launch declined.

As part of ensuring the land-based leg of the nuclear triad is ready and capable of responding to attack, the United States usually conducts four to five ICBM test launches per year. If the U.S. continued this pace of testing, it would run out of extra weapons to launch by 2035, forcing it to either halt test launches indefinitely or start shaving operational weapons off the inventory to be used for these tests.

Yet, the Air Force contends that there are several other challenges it would have to face to keep the Minuteman III alive for the foreseeable future. The first and most prominent is the aging out of the rocket motors meant to carry the weapons to their targets. Rocket motor lifespans are determined by destructively testing a small number of them and measuring the degradation of physical, chemical, and mechanical properties to create statistical models that can be used to determine when the motor’s functionality would fall below operational thresholds. In other words, they subject these rockets to immense stresses, measure the damage, and then use that data to extrapolate an expiration date for when the rocket will no longer work well enough to accomplish its mission.

Based on the Air Force’s rocket lifespan modeling, the three boosters in the Minuteman III will begin to expire in 2029.

The next technical hurdle another service life extension program would need to overcome is the weapons guidance system also aging out of service. The Minuteman III originally came equipped with the NS-20 Missile Guidance System, which had already aged out of relevance by the 1990s, prompting the branch to kick off the Minuteman III Guidance Replacement Program midway through the decade. This program saw the NS-20 swapped out for the more modern and accurate NS-50 system. This cost some $1.6 billion in 1995 currency, or roughly $3.34 billion today, and would extend the lifespan of these guidance systems out to 2020.

By 2012, the Federation of American Scientists reported that the Defense Department had already invested a total of $7 billion into various Minuteman III service life extension efforts – roughly $9.7 billion in today’s dollars, and it certainly didn’t end there.

Then, 2020 came and went without a Minuteman III replacement, and the Air Force had to award several subsequent contracts to Boeing to stretch their lifespans out to 2030 and beyond – when the Minuteman III’s replacement was meant to come online.

While not a conclusive list of these life-extending costs, public records exist for a $51.2 million contract award to Boeing for the job in January 2015 ($68.83 million today), followed by at least two contract modifications to add an additional $15.6 million the following February and an additional $8.1 million in July (a combined $31.43 million today for a total of $100.26 million).

But even with all this invested, the Minuteman III still faces a laundry list of systems that are not only aging out of relevance but aging out of being feasible to maintain and support.

A 2019 analysis conducted by the conservative think tank Hudson Institute posited that between 2031 and 2033, as many as 50 missiles might age out of service due to motor or onboard systems falling below the operational threshold, and by 2037, the operational Minuteman III fleet could be as small as 100 weapons. However, the Air Force awarded Boeing another $1.6 billion in February 2023 for Minuteman III “guidance subsystem support,” which is likely to curtail at least a portion of these losses, even if it did mean eclipsing the $10 billion mark on service life extensions.

As the Pentagon sees it, continuing to funnel billions of dollars into keeping these Kirk-and-Spock-era weapons in service simply isn’t sustainable from either financial or strategic perspectives.

As Lt. General Andrew Gabera, deputy chief of staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration explained, the Air Force has already modeled out the costs of keeping the Minuteman III relevant, but even those projections have limited value because they simply don’t know what the future may hold. Adapting to unforeseen threats would objectively be simpler (and cheaper) with a fully modern system.

In 2021, the head of U.S. Strategic Command, U.S. Navy Admiral Charles Richard, did not mince words regarding the future of the Minuteman III, saying it was simply no longer logical to pursue more service life extensions for the weapon, and issuing harsh criticisms for external calls to do so.

“I don’t understand frankly how someone in a think tank who doesn’t have their hands on the missile, looking at the parts, the cables, all of the pieces inside that. I was out at Hill Air Force Base looking at this. That thing is so old that in some cases the drawings don’t exist anymore. Or where we do have drawings they’re six generations behind the industry standard. There’s not only not anybody working that can understand them, they’re not alive anymore,” he said.

The admiral went on to highlight concerns about cyber vulnerabilities, saying the U.S. needed to replace what was “ basically a circuit switch system with a modern cyber defendable up-to-current standards command and control system.”

“Just to pace the cyber threat alone, GBSD is a necessary step forward,” he argued.

He also highlighted the changing threat environment, one of the factors the 2014 Rand analysis acknowledged would justify an ICBM replacement.

“This nation has never before had to face the prospect of two, peer, nuclear-capable adversaries who have to be deterred differently and actions to deter one have an impact on the other. This is way more complicated than it used to be,” Richard said.

The LGM-35A Sentinel ICBM program

But if replacing the Minuteman III was supposed to be the budget-friendly solution, that appears to have backfired. Originally, Northrop Grumman and Boeing were competing for the opportunity to design and field this new missile, with both firms planning to use solid rocket motors produced by Orbital ATK. However, Northrop Grumman purchased the rocket maker in 2019, giving them the ability to procure their rocket motors at cost, while Boeing would have to buy them at market rate. This allowed Northrop Grumman to significantly undercut Boeing’s proposal, and recognizing that, Boeing bowed out, leaving Northrop to pursue the contract uncontested.

The Air Force ultimately awarded the company a $13.3 billion developmental contract for the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) that would become the Sentinel ICBM in September of 2020, with a projected overall program cost of $77.7 billion by the time a new fleet of missiles, silos, and launch facilities had been constructed and put into service.

Of course, it wasn’t long before that projected $77 billion price tag began to climb. By February of 2021, the projected program cost has already risen to $100 billion, a figure that held until 2023, when the Pentagon acknowledged that the program’s cost had risen to substantially that even a “reasonably modified” version of the ongoing missile program, meant to reduce overall costs, would still likely ring in at roughly $140.1 billion — representing an 81% cost overrun over the effort’s initial projections. More recent estimates from earlier this month saw another roughly $800 million increase, bringing the current total to $140.9 billion.

While cost overruns are pretty commonplace among the Defense Department’s highest-priority efforts, an increase this substantial is not — in fact, the Sentinel’s budget woes are so severe that the program ran the risk of being canceled by law until just a few weeks ago.

Significant cost overruns in the 1980s associated with programs like the H-60 Series Black Hawk helicopter and MIM-104 Patriot Air Defense System prompted Senator Sam Nunn and Representative David McCurdy to sponsor what has come to be known as the Nunn-McCurdy Act, which mandated public reporting to Congress when Defense acquisition costs began to skyrocket.

This law has seen at least nine amendments since, with today’s Nunn-McCurdy laws identifying two types of budgetary breaches separated by severity. Significant Breaches occur when a weapon system or platform’s per-unit cost exceeds 15 percent or more of the current baseline cost, or when overall program costs grow more than 30 percent above their original baseline estimate. More severe Critical Breaches occur when costs increase 25 percent or more over current baseline estimates or 50 percent more than the original baseline estimate.

As of 2009, any program that meets the criteria for a Critical Breach is considered legally canceled unless certified otherwise by the Secretary of Defense, which is generally accompanied by a plan to restructure the program and a full written explanation of the problems — and intended solutions — for Congress.

At 81 percent above the original program cost estimate, the LGM-35 certainly met the criteria to be classified as a Critical Breach, prompting a Defense Department review of issues the program is facing and potential alternatives to continuing its development.

The results of that review were released to the public on July 8, with the Pentagon certifying the program to continue despite its immense cost for a number of reasons that could truly all be boiled down to one: The Air Force simply doesn’t have any other option.

America’s deterrent nuclear posture requires that the country maintain at least 400 operational ICBMs, and even if all the technological hurdles to extending the Minuteman III’s life could be easily overcome, testing alone will ensure that number can’t be maintained through the foreseeable future, as Uncle Sam simply starts running out missiles to launch.

“We fully appreciate the magnitude of the costs, but we also understand the risks of not modernizing our nuclear forces and not addressing the very real threats we confront,” explained Bill LaPlante, undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment.

“Based on the results of the review, it is clear that a reasonably modified Sentinel program remains essential to U.S. national security and is the best option to meet the needs of our warfighters.”

Over a 120-day review, the Pentagon considered options ranging from starting over with a new ICBM program to doing away with permanent silos in favor of road-mobile ICBM launchers like those employed by nations like Russia. However, it was determined that none of these options could meet the nation’s strategic needs without also coming with an even higher price tag.

But it isn’t all bad news for the Sentinel program. As General Andrew Gebara pointed out, the missiles have actually been progressing well through development, and while this effort is centered around the new ICBM, the vast majority of cost overruns within the program aren’t related to the weapon itself.

“It is important to remember the program that stage one, two and three of the missile have been successfully test fired already. I’m not going to say that we’ve retired every risk on the missile. But largely the issues of the missile are known issues that can be worked, and are largely okay,” he said.

The problems, it turns out, are almost entirely caused by the exploding costs of building the new missile’s command and launch facilities. While the plan is to reuse as much of the existing launch infrastructure left behind by the Minuteman III as possible, much of the communications systems, command and control infrastructure and even the launch silos themselves will need to be modernized at best and completely replaced at worst.

Based on the Air Force’s original assessment, this will require the demolition of 45 missile alert facilities (MAF’s) in the existing silo fields, to be replaced by 45 new communications support buildings in their place, with 24 new “launch centers” constructed to support them, as well as a complete renovation of all 450 launch silos.

The plans also call for the procurement of 62 plots of land, each roughly 5 acres in size, near existing missile fields to erect the same number of new 300-foot-tall communications towers, as well as the construction of some 3,100 miles of new utility corridors for utility lines to be housed entirely below ground, and a whole lot more.

As of July 8, however, the Pentagon has rescinded the program’s Milestone B decision that would have allowed the Sentinel ICBM to move into the engineering and manufacturing development phase, pending a program revamp meant to keep the program at or beneath their newly projected $140.9 billion figure. Chief among these changes will be a “scaling back” of the planned launch facilities to make them smaller, simpler, and more cost-effective.

The Air Force also fired Sentinel Systems Director, Col. Charles Clegg, at the end of June, citing a loss of confidence in his ability to lead the effort. The branch said his termination was not related to the Nunn-Mccurdy violation, but was instead because the colonel “did not follow organizational procedures.”

All told, the Air Force believes plotting out the new way forward for Sentinel may take as long as 18-24 months, and during that time, other big-ticket programs within the branch are also finding themselves in flux. The Air Force’s new air superiority fighter, being developed under the name Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD), is still expected to see a contract award this year, but senior Air Force officials have voiced uncertainty about its future, while being clear that it will have to see cost reductions — almost certainly informed by the need to pick up Sentinel’s financial slack.

Ultimately, the LGM-35 Sentinel is still expected to enter service sometime in the 2030s, though it may be late in the decade before these new weapons finally do come online. Once they’ve finally made it into their silos, these weapons are expected to remain in service until at least the 2070s, with modular systems meant to allow for cheaper and easier updates as the years press on.

Of course, there remains a growing chorus of dissenting opinions, with some arguing that the U.S. should simply continue to update the Minuteman III and simply reduce the total number of ICBMs kept in service to 300 or even just 100. This would allow for a continued land-based deterrent at a much lower cost, though others argue that doing so would defeat the purpose of using these sprawling missile fields as a conceptual shield for the rest of the nation, and importantly, the rest of the triad.

Those who contend the Sentinel ICBM program is absolutely essential to America’s deterrent nuclear posture argue that it’s not just about maintaining a large number of targets for adversaries to worry about, but it’s also about distributing the focus — and the resources — of enemy states looking for ways to work around this deterrent nuclear shield. Put simply, with fewer ICBMs to worry about, Russia and China could allocate more money toward funding ways to detect or track America’s ballistic missile submarines, potentially reducing their efficacy in the long term.

And therein lies the heart of the financial warfare that is nuclear deterrence. For the better part of a century, the United States’ greatest military asset has been a big pile of money that it can use to fuel a wide variety of defensive endeavors, but nowhere is cost a greater factor than when it comes to nuclear weapons — which are vastly expensive systems to develop, to build, and to maintain, despite having absolutely no utilitarian value beyond the threat of their use.

While new fighters or bombers could be used in a wide variety of conventional combat operations, nuclear weapons have only two potential use cases: Holding off the end of the world, or directly causing it.

And that makes the value of these high-dollar assets difficult to quantify. After all, there’s really no way to know how many times nuclear war has been deterred by the mere presence of America’s sprawling nuclear triad, if it truly ever has at all. But deterrence only has to fail once to change the face of our planet and civilization forever.

And while $140 billion is a high price to pay for a few hundred missiles, some would argue that the cost of nuclear deterrence is worth it, no matter how big the price tag.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Could paramotors be useful to the US military?

- Ukraine is the world’s largest minefield. AI is now helping to clear it

- The veteran and the beard – Like peanut butter and jelly

- Lockheed Martin’s new hypersonic missile can fit inside the F-22

- Navy wants to add decoys to its F-35s in preparation for a near-peer conflict

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Gear & Tech

Game-changing military aircraft that were canceled before they could change the game

The ultimate guide to the Patriot air defense system

Anduril’s Roadrunner is a unique reusable missile interceptor

The AGM-181 LRSO missile will modernize America’s nuclear triad

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page