Crucial Alaskan islands of WWII strategically important again

- By Business Insider

Share This Article

This article by Christopher Woody was originally published by Business Insider.

August marked the 78th anniversary of the end of the Aleutian Islands campaign, a yearlong battle along a chain of islands stretching from mainland Alaska across the northern Pacific Ocean.

The islands of Attu and Kiska were the only North American territory captured during World War II, and retaking them required brutal fighting in frigid, rugged conditions.

The battle is largely forgotten, but a thawing Arctic and competition with Russia and China mean Alaska has an increasingly significant role in US military planning.

Japanese troops headed to the Aleutians in May 1942, part of a plan to lure the US Navy to destruction at Midway. The Japanese were defeated at Midway, but the landings on Attu and Kiska went ahead in June 1942. Several thousand Japanese soldiers were eventually garrisoned there.

The US focused elsewhere in the Pacific for much of 1942, but operations to recapture the islands began in spring 1943.

The Japanese defenders took advantage of the rough terrain. It was some of the deadliest combat in the Pacific — fought amid dense fog and winds of up to 120 mph — but US troops had secured both islands by late August 1943.

During the Cold War, the military focus in Alaska shifted to air defense, with bombers and other aircraft at a few bases and radar and early-warning sites stretching across the state and northern Canada.

Russia’s military deteriorated after the Cold War, but Moscow has been rebuilding its forces as its relations soured with the US.

Russian long-range aviation patrols around the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone — which surrounds the state but is not US territorial airspace — restarted in 2007, and US officials said this year that intercepts of those flights in 2020 reached their highest level since the Cold War.

Related: Here’s why US fighters and Russian bombers keep squaring off near Alaska

Russian naval activity near Alaska has picked up as well, including a major exercise in late 2020 that was “certainly intended to demonstrate to the US and others their influence,” Air Force Gen. Glen VanHerck, head of US Northern Command, said in August.

China too has growing Arctic ambitions, seeking natural resources as well as infrastructure that some worry could have military uses. Beijing has declared itself a “near-Arctic state,” a designation that US officials often dismiss.

Chinese warships were spotted off Alaska’s coast for the first time in September 2015, and Chinese icebreakers are making more trips to the Arctic, often passing through the Bering Strait.

Chinese officials “really do see the region as important to [China’s] long-term economic and security” interests, Air Force Gen. David Krumm, head of Alaska Command, said this spring.

Beijing is also investing in Russia’s Northern Sea Route and in scientific research in the region. In 2020, China’s newest icebreaker, the Xue Long 2, “was up here all summer conducting research,” Krumm said.

Related: Military activity is picking up in the quiet waters between the US and Russia

Alaska’s strategic significance in homeland defense is longstanding — Army Gen. Billy Mitchell in 1935 called it “the most important strategic place in the world” — but recent events have been a reminder of it.

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin visited Alaska in July, calling the trip “a keen reminder of just how strategically important Alaska is to our national security and to homeland defense.”

Alaska connects the US to the Indo-Pacific and the Arctic and “is where we can project power into both regions and where we must be able to defend ourselves from threats coming from both places,” Austin said.

Receding Arctic sea ice is “opening the region to growing maritime activity and increased competition,” the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard said in a joint maritime strategy released in December 2020.

Each of those services is focusing more time and resources on the Alaskan Arctic.

The Coast Guard has just two aging icebreakers, and it is easing them through operations there — including a Northwest Passage transit that began in late August — as more are built.

The Navy has increased its presence around Alaska — aircraft carriers sailed there for exercises in 2019 and 2021 — and work is underway that support more naval activity, including construction of a deep-water port in Nome, which would be the first in the US maritime Arctic.

The Navy’s top officer, Adm. Michael Gilday, said last year that he expected the Bering Strait to be “strategically as important as the Strait of Malacca or the Strait of Hormuz.”

The Marine Corps has no active units stationed in Alaska, but Corps leaders are looking at ways to do more there.

Current and former Marines have called for a more robust Corps presence in Alaska, with one officer calling the Aleutians “perfect terrain” for testing expeditionary-warfare capabilities.

The Army has put renewed focus on the Arctic, and the Army Arctic Strategy released this year emphasized a need to improve its training and capabilities in Alaska.

“I think it’s an exciting time to be in Alaska and come to Alaska. It’s a phenomenal place to live, and the Army’s investing in it,” Maj. Gen. Peter Andrysiak, then-head of US Army Alaska, told Insider this spring.

The Air Force has the military’s largest Arctic presence, overseeing nearly 80% of Pentagon resources there.

That footprint is only growing. With over 50 F-35s deploying to Eielson Air Force Base and over 50 F-22s at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska will be the state with highest concentration of combat-coded fifth-generation fighters.

Alaska is also home to the Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex, a sprawling area where US and foreign militaries train in Arctic conditions on land, sea, and in the air.

The Air Force plans to upgrade JPARC’s “threat replication” capabilities to Level 4, or that of a near-peer, but won’t be done until 2032.

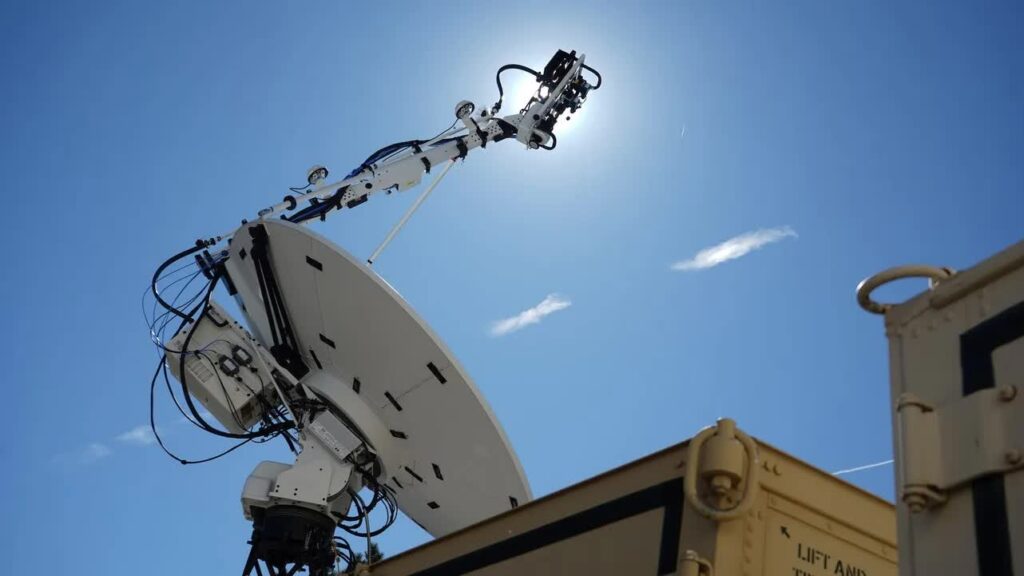

Space Force, the newest military branch, also has a small presence in Alaska at the recently renamed Clear Space Force Station. Clear hosts the Long Range Discrimination Radar, which is meant to find threats among the clutter in the sky and space.

“We are now doing radiation, which means the radar is up and running, doing low-power calibration, and we are going to learn a lot,” Adm. Jon Hill, director of the Missile Defense Agency, told senators in June.

At an event in July, Lt. Gen. Clinton Hinote, Air Force deputy chief of staff for strategy, integration, and requirements, admitted that people working on Arctic issues “are probably sick of hearing” Mitchell’s quote but said it remains true.

“There’s a special place for Alaska when you talk about power-projection and defense of the homeland,” Hinote said. “There are so many things that we believe are important about that area, and we are plussing-up the military power that is there.”

Read more from Business Insider:

- US Special Operations Command has given up on its ‘Iron Man suit,’ but it’s still looking for other high-tech upgrades for its operators

- New York Times report details the chaos that unfolded after Afghans were evacuated to Doha including ‘rogue’ flights

- Mexico’s most dangerous job is only getting more deadly, and I’ve seen up close how bad it’s getting

- Ukraine lured suspected Russian war criminals out of the country with fake, $5,000-a-month jobs to try and arrest them, report says

- China is irritating more countries in Asia, but the US is struggling to come up with a better offer

Feature image: U.S. Marine Corps photo by LCpl Brendan Mullin

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

Business Insider

Related to: Military Affairs, Military History

Space Force to deploy new jammers to yell at enemy satellites

Congress demands answers on low testosterone issues among special operators

Video: US military sends aircraft to help with LA fires

Video: DARPA wants to arms a missile with cannons

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page