America’s Replicator Initiative signals a shift in combat philosophy

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

The Pentagon-wide effort, known as the Replicator Initiative, to field thousands of low-cost drones across all warfighting domains may be less than a year old, but its first batch of high-volume weapon systems is already arriving in the Pacific with its sights set squarely on deterring China.

Last September, Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks announced the Pentagon’s Replicator Initiative, which aims to field “multiple thousands” of low-cost drones operating in air, land, and sea within the next two years, with a cost of around one billion dollars. That is, of course, a huge sum of money, but when it comes to fielding entire fleets of semi-autonomous collaborative warfighting machines, a billion dollars could be seen as a downright bargain.

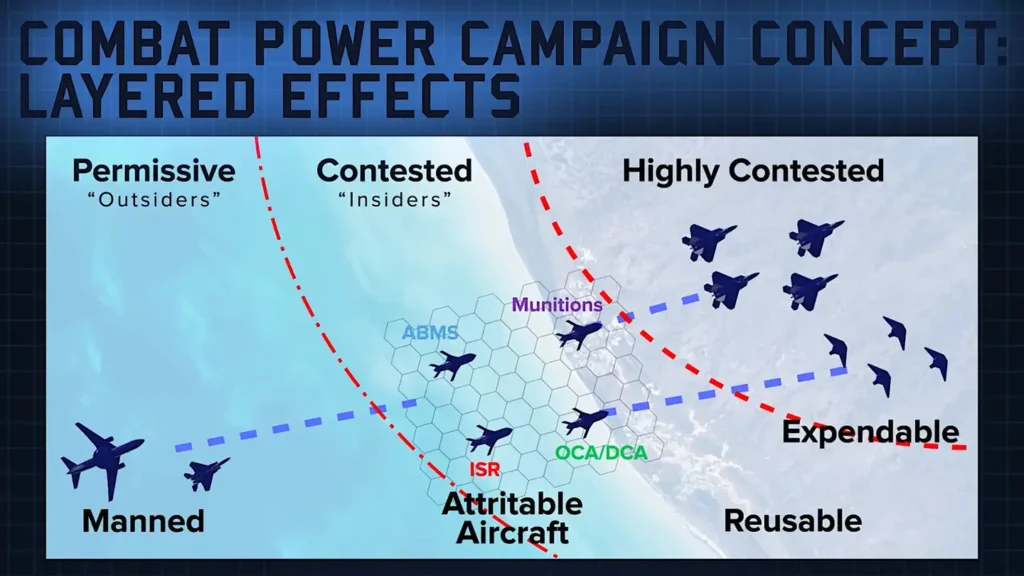

Instead of seeing this as a new program, Replicator might be better thought of as a new philosophy – steering the priorities of new acquisition efforts toward what the U.S. Air Force has long called, “affordable mass.”

After decades of U.S. Defense efforts focused on fielding broadly capable and supremely expensive high-end platforms like the F-35 and forthcoming B-21 Raider, the Pentagon now believes the best way to leverage these pricey systems isn’t to send them into the fight alone, but rather, accompanied by a veritable hornet’s nest of other systems, thus dramatically increasing the force’s overall combat capacity for far less than would be required if fielding strictly high-end platforms.

Perhaps even more importantly, it also means significantly complicating matters for adversary air defenses, which may have already struggled to identify and target America’s stealthy fighters and bombers, but will now be forced to contend with hundreds, or potentially even thousands, of other targets pouring into their airspace.

While this concept seems to go hand in hand with the Air Force’s recent efforts to develop and field highly capable Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCAs), or AI-enabled drones meant to fly alongside its most advanced fighters into combat, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall was quick to point out that CCA is not a part of the Replicator effort.

This is almost certainly because, as Hicks laid out, Replicator aims to field a large number of inexpensive drones with a shelf life of just a few years each, whereas the Air Force’s CCA program aims to field extremely capable Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles with modular payloads and at least some degree of stealth that will likely serve in varying capacities for much longer and are designed to be able to accommodate rapid upgrades and improvements.

Although, the CCA program is looking to field far more expensive platforms than the Replicator, the fundamental philosophy driving both efforts is, nonetheless, very similar. Replicator is all about increasing the number of combat platforms in the battlespace, without increasing the number of actual human operators in harm’s way.

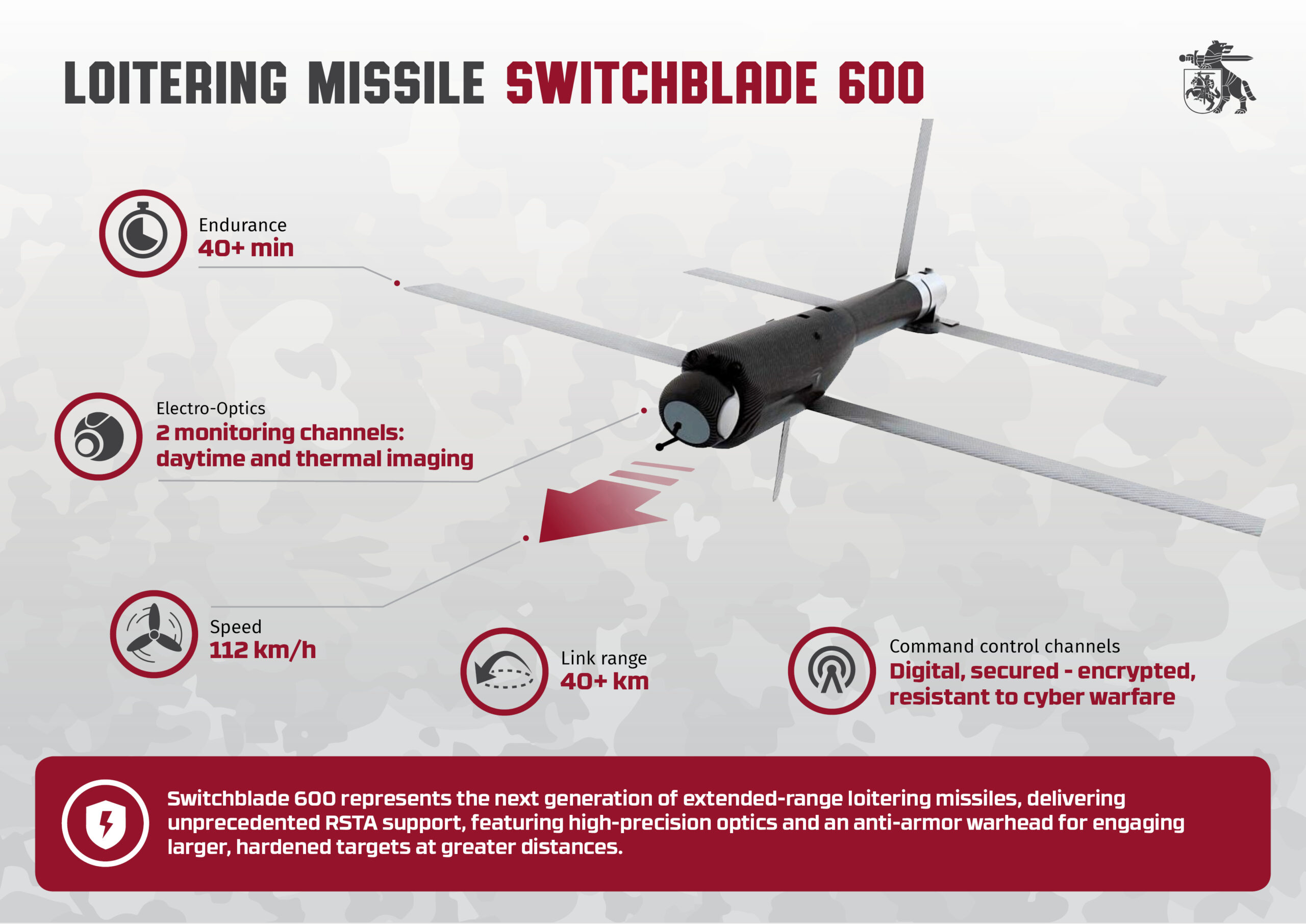

In May, the Pentagon announced the first platform to benefit from the Replicator Initiative’s expedited acquisition process would be AeroVironment’s Switchblade-600. This system, commonly referred to as a “suicide drone,” might be more aptly described as a loitering munition. Both the Switchblade 600 and its older and smaller sibling, the Switchblade 300, have already proven to be extremely effective in the sprawling battlefields of Ukraine, where Ukrainian forces have used them to engage Russian troops behind defensive lines, and perhaps most importantly, as an extremely potent tank-hunter.

Related: Video: Russia claims Ukraine’s F-16s will carry nukes

Switchblades in Ukraine

A wide variety of drones have proven invaluable for engaging Russian armor at long range, with many used to identify tank positions to relay their coordinates back to artillery teams. Switchblade loitering munitions, on the other hand, do not need to rely on artillery support. Instead, these systems can be deployed by infantry units in the field, with sufficient range and loiter time to look for and identify threats still miles away, and enough onboard explosives to engage those threats themselves once located. This has proven invaluable for Ukrainian forces, who often find themselves both outnumbered and outgunned.

Russia’s warfighting doctrine, while proving largely ineffective at securing overall victory, has also produced several battlefield advantages over Ukraine’s piecemeal defense. Because of NATO’s airpower-centric approach to warfare, Russian warfighting doctrine assumes the country would lack the airframes and weapon systems required to take, secure, and maintain air supremacy in a large-scale fight. As such, Russian planners have instead emphasized what they call, “fire superiority” instead. This calls for a massive emphasis on long-range fires delivered via a variety of artillery and missile systems, with Russian military leaders treating tactical aircraft as an extension of this warfighting model, rather than as a power unto themselves.

As a result, Russia operates some 4,780 artillery systems of varying sorts, versus Ukraine’s approximately 1,600. But while Russia’s fire-superiority model has provided a palpable artillery advantage on the battlefield, it has also left the airspace over Ukraine contested nearly two and a half years into their invasion, thus creating opportunities for systems like Switchblade to have a massive impact.

“The Ukrainians don’t have the artillery firepower of the Russians, they don’t have the the expendable human capital of the Russians,” AeroVironment Vice President Charlie Dean told Newsweek last October. “The unmanned systems, include the loitering munitions, play a huge role in really offsetting the balance of firepower.”

Of course, the United States military doesn’t face many of the same challenges that Ukraine does – boasting among the largest active military forces on the planet and the most sprawling and advanced military footprint in the entirety of human history. But even for a global powerhouse like the U.S., numbers can be a serious challenge.

Airpower en mass

Despite America’s massive defense expenditures, the number of warships, fighter planes, and similar platforms in the U.S. arsenal has been steadily decreasing for decades. This has come, in large part, thanks to rapid advances in a variety of technologies that allow fewer platforms to fill more roles; and nowhere is that more apparent than in the world of tactical aircraft.

On the flight decks of America’s aircraft carriers, for instance, we’ve seen a rapid consolidation of airframes since the end of World War II, with specialized bombers, attack aircraft, reconnaissance platforms, and more being replaced by more broadly capable fighters. Even the Navy’s primary electronic attack aircraft today, the EA-18G Growler, is fundamentally a fighter as it shares an airframe with the F/A-18 Super Hornet and carries air-to-air missiles for self-defense.

America’s multi-role approach to air warfare has allowed it to focus on fielding some of the most advanced and broadly capable tactical aircraft ever to take to the skies, each equipped to fly a multitude of missions depending on operational requirements.

There’s no denying this has been an extremely cost-effective approach to power projection throughout the asymmetric conflicts of recent decades, but in a high-end fight, losing these platforms could have a disproportionate effect on capacity. No matter how multirole your aircraft is, it can still only be in one place at one time… and with fewer platforms than ever, losing a single modern fighter represents a much more significant loss than it would have in past eras.

As Marine aviator Dennis Santare and Navy veteran Chris Trost wrote for the Oliver Wyman consultancy earlier this year, “Superior technology is an advantage the United States military has historically leveraged to deter, fight, and win wars. But it’s not just advanced weaponry that has helped us fend off enemies. Our strength has also depended on our ability to mass combat power to overwhelm adversaries.”

Building a single F-35C, the carrier-capable iteration of the stealth fighter, requires a jaw-dropping 60,121 combined man-hours, according to a 2018 report from the Government Accountability Office.

Conversely, it was reported during World War II that 20 carrier-capable F4U Corsair fighters could be built in 240,000 man-hours, which shakes out to approximately 12,000 man-hours per carrier fighter. In other words, it takes approximately five times the man-hours to replace a modern carrier fighter than it would have 80 years ago.

By the end of World War II, the United States was operating nearly 300,000 military aircraft of all sorts, today, that number has dwindled to fewer than 14,000.

When you consider the broad range of capabilities delivered by America’s modern multirole fighters, this disparity certainly makes sense, but that doesn’t change the problem this shift represents. America’s platforms may be incredibly capable, but they’re extremely expensive, hard to replace, and exist in too few numbers to withstand a large-scale conflict against a near-peer adversary. And that’s before you consider the potential losses of aviators and crews, or longstanding concerns about readiness rates among America’s most advanced systems.

With recruiting continuing to struggle across most branches, an increase in autonomous systems can also help Uncle Sam offset the numerical advantage authoritarian regimes enjoy when it comes to hard numbers. Barring a military draft spurred by the onset of World War III, the United States is, to some extent, at the mercy of its population when it comes to fielding a larger number of troops – including pilots.

The solution, the Pentagon has assessed, is to field a broad range of new systems meant to offer a return to airpower en masse. Yet, rather than fielding a high volume of inexpensive manned aircraft operated by sizeable aircrews, the U.S. now wants to field a variety of inexpensive and often “attritable” drones to supplement high-end crewed fighters and bombers.

Related: ‘Counterculture’ approach enabled C-130’s 26-hour marathon flight

The need for volume in the Pacific

The Replicator Initiative’s extremely aggressive timeline, aiming to field thousands of new systems in just two years, highlights the importance of shoring up the numbers well ahead of a conflict breaking out. As is the case with all of America’s highest-profile defense initiatives, the real aim is not to field a force that can win an eventual conflict with China, for instance, but rather, to field one so powerful that could deter China. Put simply, the United States aims to ensure China won’t turn to military force to achieve its strategic objectives because the cost would simply be too high.

But with several senior Defense officials claiming China appears to be positioning itself for military action against Taiwan by 2027, that leaves very little time for America’s massive and sluggish military machine to transition away from its asymmetric counter-terror mindset, adjust training practices, relocate assets, and bulk up its Pacific presence to deter that invasion before it begins.

Surprisingly, however, that transition and build-up has already begun, with the Replicator Initiative’s first shipment of systems reportedly arriving at the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command earlier this year. Based on previous announcements, it’s assumed that this shipment includes several Switchblade 600 systems, though the Pentagon has clarified that, “the first tranche of Replicator also includes certain capabilities that remain classified, including others in the maritime domain and some in the counter-UAS portfolio.”

The Switchblade story

The Switchblade’s road to service began in 2004 when the U.S. Army approached AeroVironment to develop an unmanned aerial vehicle that was small enough to be launched out of a standard 105mm mortar tube. The concept of operations was very similar to how we’ve seen drones employed on the battlefields of Ukraine.

By 2006, the mortar-launched drone had proven so effective that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) stepped up to fund the development of what they called a “Close Combat Lethal Reconnaissance” tool based on the same premise, but with the added ability to directly engage targets on its own.

The original Switchblade, which has since been rebranded as the Switchblade 300, was largely born out of this effort, with both the U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command and U.S. Army stepping in by 2010 to continue funding development, under the name (at the time) of Lethal Miniature Aerial Missile System.

While many may refer to these systems as “suicide drones,” those early Switchblades were much more missile than drone. At just 5.5 pounds and about 19.5 inches long, the Switchblade 300 can easily be stowed inside a backpack. Once launched from a standard mortar tube, its spring-loaded wings and stabilizers pop out, giving it a wingspan of around 27 inches (68.6 cm), allowing it to cover distances of around six miles at speeds of around 100 miles per hour, using an electric motor for propulsion with enough battery life to support about 15 minutes of loiter time.

Operators can use the same control unit for the Switchblade 300 as other small drones already in service like the Raven, Wasp, and Puma, using daytime color and infrared video feeds bolstered by GPS guidance to locate, identify, and engage targets with an onboard warhead roughly equivalent to a 40mm grenade. The Switchblade 300 10C, one of the earlier iterations of the system, came equipped with a low-probability of intercept Digital Data Link (DDL), a new multi-pack launcher to make it possible to deploy multiple Switchblades at once, and an “Aided Target Tracker” system to lock in onto and engage moving targets.

Importantly, however, the Switchblade system doesn’t require a great deal of training to use, with the onboard computers handling the actual flying, and the drone operator tasked with little more than directing the system.

“[Unlike] radio-controlled devices, the operator is not flying the aircraft, the operator’s simply indicating what he wants to look at, what he wants the camera to be pointing at, and the onboard computer flies the aircraft to that point and maintains on target,” Steve Gitlin, AeroVironment’s Chief Marketing Officer, told The War Zone in 2020.

The system soon proved so effective that a much larger iteration, known as the Switchblade 600, emerged in 2020, and has since been identified as the first purchase from the Pentagon’s Replicator program.

This system is still man-portable but is significantly heftier at 60 inches long and around 120 pounds, including a launch tube and fire control system (the weapon itself weighs around 65 pounds). The system can be set up and launched in about 10 minutes. AeroVironment claims the Switchblade 600 can fly out to around 25 miles in just 20 minutes or so, and then provide another full 20 minutes of loiter time once on station. This could potentially allow the 600 to reach targets as far away as 56 miles, though doing so would require relayed antennas positioned along the way to get commands to the system. A larger electric motor allows this system to sprint to speeds as high as 115 miles per hour, or loiter at speeds of around 70 mph.

The 600 offers improved guidance, with a tap-to-target function on the fire-control tablet to dramatically increase ease of use for the operator, who can keep tabs on the action via the system’s electro-optical and infrared sensors.

“The operator directs it on a path and monitors the orientation of the drone with live High Resolution (HR) streaming video to the Ground Control Unit (GCU). A target is identified and locked onto by the GCU at which point it flies autonomously to its destination,” explained retired Delta Force operator and Sandboxx News contributor George Hand.

The 600 carried a warhead comparable to a Javelin anti-tank guided missile, making it particularly well suited for engaging enemy armor.

Replicating the Switchblade

The Switchblade 600 system provides infantry warfighters on the front lines with the ability to provide their own ISR and air support – locating, identifying, and even engaging enemy positions from miles away.

With a demonstrated successful track record in Ukraine, the Pentagon identified the Switchblade 600 as the first of what’s sure to be several Replicator acquisitions. But single-use systems like the Switchblade 600 are only valuable if they can be produced in high volume for relatively low cost.

In October 2022, after some 400 Switchblade 300s had already been delivered to Ukraine but shortly before the first Switchblade 600s arrived, AeroVironment’s Charlie Dean told DefenseNews that the company already could produce around 2,000 Switchblade 600s per year, but was already scaling up that capacity with the aim of reaching 6,000 systems per year in 2023. It’s extremely likely that this increased capacity played a significant role in the system’s selection for the Replicator Initiative, as it was an already mature capability with the existing production infrastructure required to meet the Pentagon’s aggressive timeline.

Thus far, the Pentagon has not shared what other systems are being considered for subsequent Replicator-based purchases, though it has been clear that not all of these systems will be airborne, as the U.S. has a pressing need for a high volume of networked assets in all warfighting domains.

But the flying assets fielded by the Replicator effort will ultimately provide a great deal of mass for the Air Force’s intended High/Low mix of aircraft, weapons, and adjacent systems meant to saturate enemy air defenses.

The Air Force intends to award the contract for its first 6th generation stealth fighter, being developed under the title Next Generation Air Dominance. This fighter is meant to fly at the center of a constellation of aforementioned collaborative combat aircraft, with contracts already awarded to both Anduril and General Atomics to further mature their designs for that role – though the Air Force has stated that subsequent contract awards may still go to other firms.

The forthcoming Block 4 upgrade for the F-35 will enable it to fly alongside these AI-enabled wingmen as well, and Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has already announced his intention to purchase at least 1,000 of these CCA drones, with 600 drone wingmen meant to fly alongside 300 Block 4 F-35s, and the remaining 400 assigned to the first 200 NGAD fighters to enter service.

Other efforts, like the Air Force’s ongoing Golden Horde program, aim to field not just collaboratively networked munitions similar to the Switchblade 600, but work has already begun on collaborative miniature air-launched decoys (MALD). These systems are launched from aircraft like cruise missiles, but carry specialized RF transmitters onboard to mimic the radar return of any aircraft, creating ghost targets to further saturate and overwhelm the battlespace. The ADM-160 MALD has already been in service for some time, with early iterations like the ADM-160B even seeing service in Ukraine. However, these new collaborative decoys will be able to integrate with a broader network of systems to maximize their efficacy as both decoys and as electronic warfare and jamming assets.

So, while the Replicator Initiative continues to gain steam, it might be best to see this ongoing effort as just one aspect of a new American combat philosophy – one that places equal emphasis on the sheer volume of assets in the battlespace alongside the overall capabilities of its systems. Because, as the United States is coming to appreciate, quantity has a quality of its own.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The Russian A-545: An oddball AK rifle in Ukraine

- Congress to the Air Force: Buy More F-15EX Eagle IIs

- 4 Royal Marines once strapped themselves to attack helicopters and rode into a Taliban compound

- A realistic analysis of what F-16s can really do for Ukraine

- US SpecOps were the vanguard of a revolution in battlefield medicine

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Gear & Tech

A Green Beret remembers his favorite foreign weapons

The AGM-181 LRSO missile will modernize America’s nuclear triad

Navy will soon announce the contract award for its F/A-XX 6th-generation jet, according to reports

America’s new air-to-air missile is a drone’s worst nightmare

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page