America almost built its own version of China’s new stealth jet 20 years ago

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

On December 26, 2024, two new Chinese aircraft broke cover for the first time, demonstrating a significant leap ahead of current Chinese stealth technology and raising concerns about the future of American air superiority. The larger of these two aircraft, dubbed the “J-36” by the media, boasts a stealthy delta-diamond wing configuration with no standing vertical tail surfaces, allowing for both a massive increase of internal volume for larger fuel stores and payloads and a significantly reduced radar return across different broadcast bands and angles of observation.

For many with only a passing interest in aviation technology, this new aircraft seemed to suggest that China’s rapid military modernization efforts had now matured to the point of surpassing American low observable technology, drawing comparisons between this new stealth aircraft and the tailless renders we’ve seen depicting America’s own next-generation stealth fighter — now a full decade into development, but currently halted due to budgetary shortfalls.

And while it’s important that we not discount or dismiss the rapid progress China has made in this realm or the threat these new aircraft could pose, it’s equally important that we look at these developments in the full context of our time.

Because as groundbreaking as China’s new tailless stealth fighters may genuinely be for China, the concepts and technology informing their design largely aren’t. In fact, more than a quarter-century ago, before the F-22 even entered service, Lockheed Martin was already designing stealth aircraft based on the soon-to-be-legendary Raptor that demonstrated vital aspects China’s new stealth jet’s design. In fact, in the early 2000s, the United States Air Force even intended to purchase more than 150 of these stealth fighter/bombers, appropriately dubbed, the FB-22.

The F-22 Raptor was the perfect platform to build upon

When the F-22 entered service in 2005, it represented such a significant leap ahead of anything flying at the time that the very concept of fighter generations largely took hold in the American lexicon specifically as a way to convey just how terrifying this new fighter would be for pilots stuck squaring off against it in jets of previous generations. At a time when many of the world’s more prominent air forces were still operating 3rd generation fighters, the Raptor emerged as a flying symbol of America’s engineering prowess, airspace dominance, and maybe most of all, its deep pockets.

But what many people don’t know about the F-22’s path to service is that it was almost so much more capable than the jet we ultimately got. During the Raptor’s path to service, several capabilities that would have made the most dominant fighter of our time even better were whittled away from production plans in an effort to bring costs down amid America’s transition toward the asymmetric conflicts of the Global War on Terror. In other words, the F-22 would have been an even more dominant fighter over the past two decades and through today, were it not for the shortsighted belief that America wouldn’t need to worry about air superiority in a post-Soviet world.

Some of these capabilities are only now finding their way into the F-22 line, thanks to an ongoing nearly $11 billion upgrade that’ll see roughly $72.6 million invested into each of 150 or so operational Raptors. For context, that means each F-22 will receive upgrades nearly comparable in cost to fielding an entirely new F-35A, including infrared search and track targeting capabilities and helmet-mounted displays — both systems that were originally intended to reach service with the first jets to roll off the production line in 1997, but will now likely be in use fleet-wide by 2029.

Other capabilities that were cut are unlikely to ever see service, like side-mounted radar apertures that would have given the F-22 a significant boost in situational awareness, intelligence-gathering capabilities, and perhaps most importantly, targeting. The F-22’s AN/APG-77 active electronically scanned array radar was, hands down, the most powerful targeting array ever affixed to a fighter at the time, but additional sideways-looking arrays would have allowed the F-22 to fly perpendicular to contest airspace while peering deep inside, mapping the locations of adversary assets and even locking onto targets if needed. Two-seat F-22 Raptors that could operate alongside the single-seat iteration were also a part of the original production plan but ultimately scrapped.

It’s incredible to think of what the F-22 Raptor could have been, had it entered service with these additional capabilities two decades ago, considering the platform went on to become so dominant for so long without them. In fact, with the addition of IRST, helmet-cued targeting, and new stealthy external fuel tanks to extend the Raptor’s range, there’s a reasonable argument to be made that it will remain the most dominant fighter in the sky for years to come, as Russia’s Su-57 and China’s J-20 both still fall short of the F-22’s combination of stealth, sensor fusion, and brute-force performance, despite emerging more than a decade later.

But even as the first F-22 test pilots were just beginning to put the production Raptor through its paces, Lockheed Martin was already looking ahead to other mission sets, and other threats, the Raptor could take on, in much the same way McDonnell Douglas found continued success with its Eagle line by modifying the F-15 for interdiction bombing duties in the F-15E Strike Eagle, while seemingly also pulling from the Strike Eagle’s own highly capable competition, in the F-16XL.

This line of thought led to a design proposal for an F-22 Raptor-based interdiction bomber, or maybe strike fighter (depending on which side of the fighter/bomber aisle you feel it lands on), appropriately dubbed the FB-22.

Related: F-22 fleet is getting upgraded threat-detection sensors to stay on top

The FB-22 was a ‘regional bomber’ based directly on the Raptor

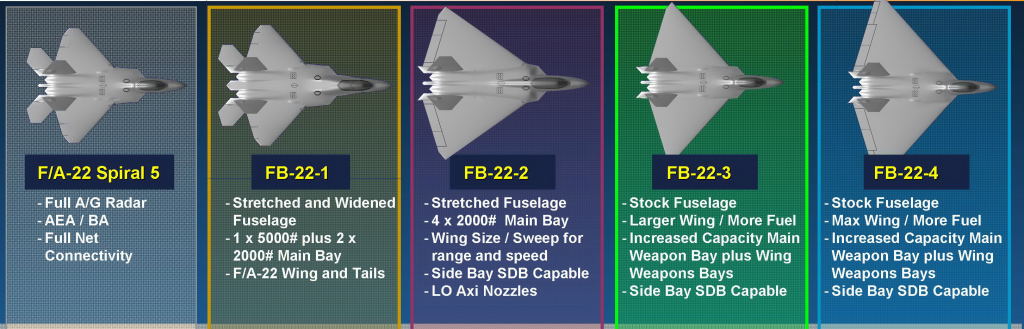

In our analysis of China’s recently revealed “J-36” stealth aircraft, we discussed how similar the center fuselage and payload bay portions of the new jet were to its Chengu-designed sibling, the J-20 Mighty Dragon, though stretched to some extent for larger internal payloads — a design approach we compared to the F-16XL concept at the time, but admittedly might be better compared to Lockheed Martin’s FB-22. Like the J-20, the F-22’s design focus was the air superiority mission, but like all modern fighters, these are truly multi-role platforms with mature, though perhaps limited, air-to-ground strike capabilities. In fact, for some time, the Raptor was commonly referred to as the F/A-22 for this very reason.

This strike capability came in the form of two 1,000-pound GBU-32 JDAMs (Joint Direct Attack Munitions) carried internally alongside a pair of AIM-120 AMRAAM air-to-air missiles for self-defense, and as such, converting the Raptor into a fighter/bomber wouldn’t necessarily require a significant departure from the avionics and other onboard systems already in production. Instead, the most significant design changes were to the fuselage, wings, and its approach to weapon storage.

Unlike older non-stealth fighters which carry their munitions on pylons on the wings and fuselage, stealth fighters like the F-22 must carry their ordnance internally in order to maintain their sleek and stealthy profile. The FB-22 would have done the same in a primary weapons bay, but also would have offered additional weapon storage in faceted, stealth weapon pods mounted underwing in an approach similar to the stealth fuel tanks now being tested for the Raptor’s upgrade.

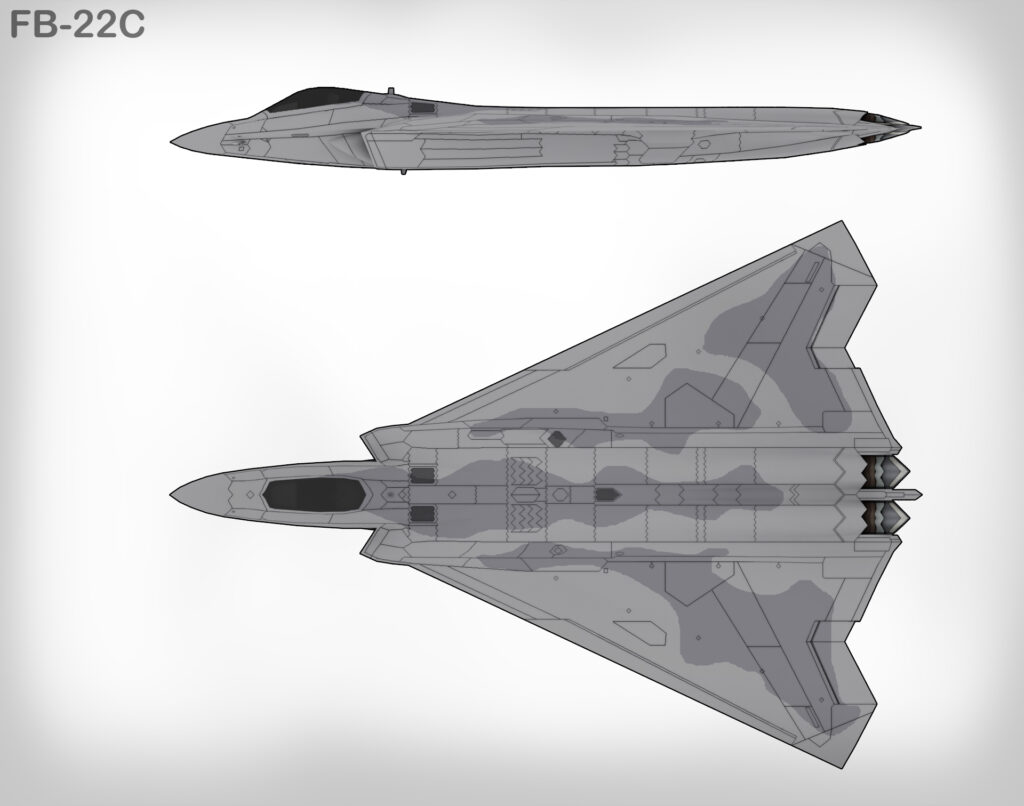

While there’s no way to know if China’s J-36 aims to use similar weapon pods, it seems unlikely based on the sheer size of the aircraft’s internal payload bay and the complexity of designing such pods. However, the J-36 does share the FB-22’s design approach of expanding the fuselage and then marrying it up to a significantly larger wing area to improve lift and offer a big boost in internal fuel storage inside those expanded wings. A half dozen different potential FB-22 wing designs were proposed to the Air Force, each offering different possible ranges and payloads.

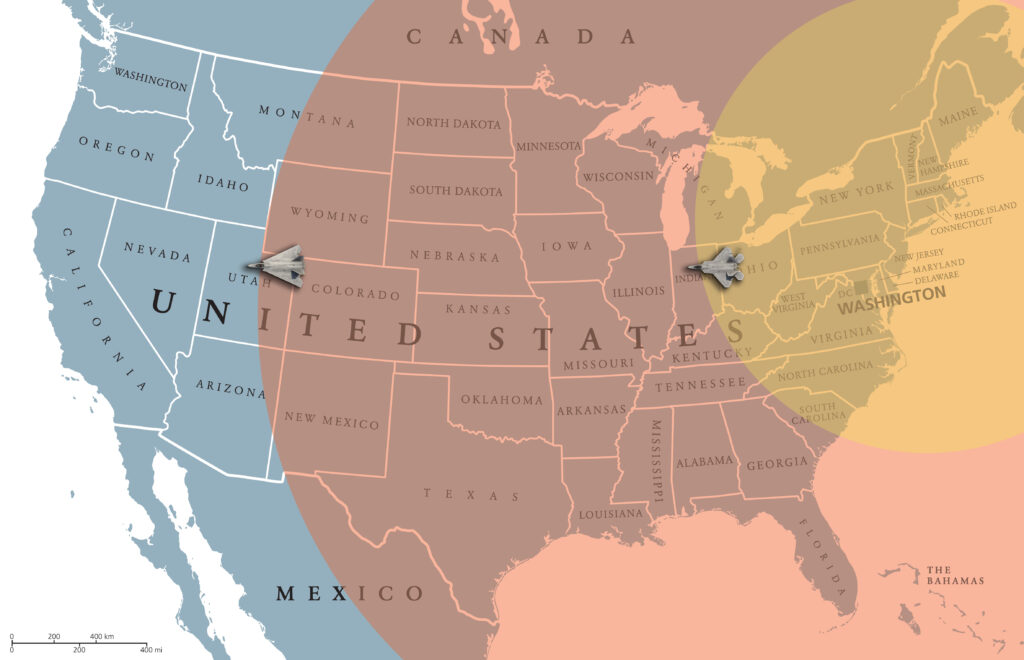

The design eventually meant to enter service offered three times the wing area of a standard Raptor and a hypothetical fuel range of a whopping 1,800 nautical miles, which is well north of 2,000 miles for those of us who aren’t pirates, suggesting a greater than 1,000-mile combat radius (something the U.S. Air Force could certainly use today). This type of range would easily classify the FB-22 as a “regional bomber,” which is a title also commonly associated with China’s J-36.

The F-22 Raptor’s payload bay is large enough to carry eight 250-pound bunker-busting small-diameter bombs, (weapons far more capable than their simple-sounding names suggest), but in keeping with its fighter-bomber mission set, the FB-22 would increase that to a minimum of 35. And while the biggest bombs the F-22 can carry are in the 1,000-pound class, the FB-22’s larger payload bay would allow for weapons up to and including 5,000-pound bunker busters, according to claims made by John E. Perrigo, the senior manager of combat air systems for Lockheed Martin’s business development branch at the time.

Like the J-36, the FB-22 would also omit the thrust-vectoring capabilities found on the Raptor and along with it, some degree of maneuverability. This was deemed an appropriate trade-off for the ability to cart some 15,000 pounds of ordnance into the fight while maintaining a stealth profile, and a whopping 30,000 pounds worth of hate when flying angry, or without concerns for detection.

Also like the J-36, Lockheed Martin proposed fielding the FB-22 without its massive standing vertical tail surfaces. These massive surfaces on today’s Raptor provide ya control and are canted outward to reduce their radar reflectivity (which also happens to benefit lift). When approaching from head-on, they do little to increase the aircraft’s radar return against high-frequency targeting arrays. However, as we’ve discussed in the past, these control surfaces (and other elements of fighter designs) can sometimes produce a detectable resonance against lower-frequency early warning radar arrays, as well as increasing the fighter’s radar return from angles other than head-on. By eliminating those control surfaces, the FB-22 would see a significant increase in all-aspect stealth in exactly the same way China aims to with their J-36.

Related: The Air Force made Lockheed’s Skunk Works design a stealth pole

Of course, like the elimination of thrust vector control, this change would also come with a reduction in aerobatic maneuverability, effectively traded in favor of reduced detectability. This is also a clear trade-off made by the designers of China’s J-36. Air Force Secretary James Roche said at the time that the FB-22 would be limited to 6 G maneuvers while flying with a full payload, and it seems likely that the J-36 offers similar aerobatic prowess.

This tailless design was also explored in Lockheed Martin’s other Raptor derivative project, the X-44 Manta, which bears perhaps the strongest resemblance to America’s NGAD fighter concept renders released to date. However, the decision was ultimately made to field the FB-22 with those standing tail surfaces intact in order to keep the cost of production and flight control software to a minimum.

In another apparent similarity to the J-36, Lockheed Martin envisioned their FB-22 as a two-seat aircraft, which would be particularly important on long-duration bombing missions that could see the jet in flight for 15 hours or more in a single sortie, with the second crewmember serving as another pilot or as a weapons systems officer (akin to the F-15E Strike Eagle) as needed.

This, Lockheed Martin believed, wouldn’t be difficult to accomplish, as they had already intended to field a two-seat variant of the Raptor. However, the F-22 would have used a tandem seat layout, whereas its rumored the J-36 may have its two crewmembers sitting side-by-side.

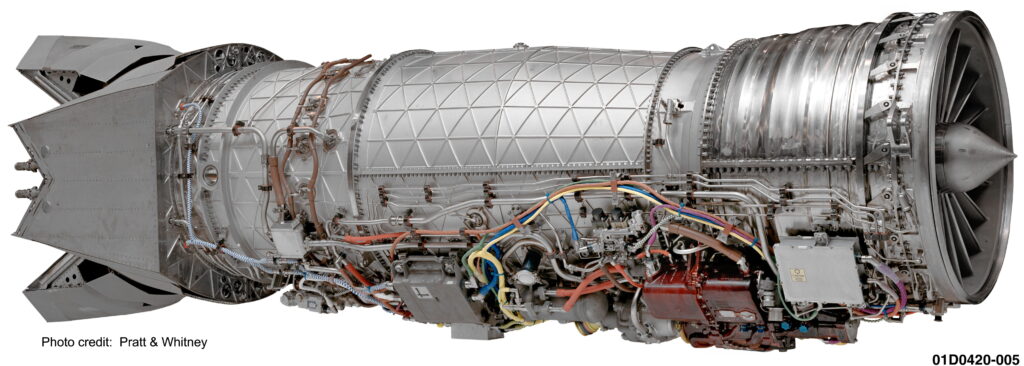

The FB-22 was to be powered an updated pair of the Raptor’s own Pratt & Whitney F119 turbofan engines — which it’s worth noting were so advanced at the time that today, both China and Russia are still struggling to field comparable powerplants for their own stealth fighters today. These engines would have propelled the much heavier FB-22 to top speeds potentially as high at Mach 1.92, or as low as Mach 1.5 (depending on variant), and this highlights the most prominent difference between the FB-22 and China’s J-36: the number of engines housed within the fuselage. This difference, however, might simply be a product of China’s inability to field more powerful engines with high production volumes.

The F-22 Raptor’s F119 engines get less attention than the jet’s stealth and sensor fusion, but were arguably just as groundbreaking for their time. These engines produce more thrust without their afterburners engaged than the F-15 Eagle could pump out with its afterburners at full tilt, and when you actually fire up the Raptor’s afterburners, the fighter offers more power than you could get out of the SR-71 Blackbird. And despite offering a big boost in power output over previous engine designs, the F119 came with 40% fewer individual parts, bringing down maintenance requirements and production costs. This engine would go on to become the basis for the F-35’s F135 powerplants, that each produce a whopping 43,000 pounds of thrust under afterburner.

The Raptor’s two F119s offer a combined 70,000 pounds of thrust under afterburner, or roughly the same power output provided by all four of the B-2 Spirit’s GE F118 engines, though the upgraded engines for the FB-22 would have prioritized power in the subsonic regime and likely would not have been able to supercruise (or maintain supersonic speeds without the use of its afterburners). A 5,000-pound improvement in maximum thrust output would have put the FB-22 in the 80,000-pound thrust class.

Conversely, it’s believed that China’s J-36 is designed to maintain supersonic speeds for extended periods of time, flying at extremely high altitudes (like the Raptor) to maximize line-of-sight for its onboard sensors and the reach of its onboard air-to-air weapons. But because China has thus far struggled to produce such broadly capable and powerful engines at volume, they seem to have turned to a three-engine layout instead.

In testing, it’s been reported that the J-36 may be powered by three WS-10C turbofan engines — the same interim powerplant in their standing fleet of J-20 stealth fighters as development continues on its intended WS-15 engines. Each of these engines are rated for something in the neighborhood of 32,000 pounds of thrust under afterburner, giving the aircraft a combined 96,000 pounds of thrust on tap for high-speed sprints, and maybe roughly 16,000 pounds more than the FB-22 might have offered.

However, its unique engine layout comes with similarly unique intake concerns, with two intakes on either side of the bottom of the fuselage and a third protruding from the top.

This layout might not allow for all three engines to gulp up as much air as they’d need to push maximum thrust depending on flight state, and indeed, that third engine might primarily be there to help support long-duration supersonic flight specifically. At high altitudes, most radar arrays looking for the J-36, including those on tactical aircraft, would be below it, making the compromise that dorsal intake forces in the jet’s stealth less pronounced.

In 2003, Air Force Secretary Jim Roche said he intended to purchase 150 of Lockheed Martin’s FB-22 fighter/bombers, meant to operate alongside a growing fleet of air superiority-focused F-22 Raptors by 2018. However, in 2006, a Quadrennial Defense Review aimed at slashing costs saw the FB-22 plans canceled, and Raptor production itself reduced to just 186 airframes, roughly 150 of which would be combat-capable.

Of course, 18 years later, the world would see a very similar concept emerge from Chengdu China, flying alongside China’s two-seat J-20S that appears to share its design DNA.

Related: It doesn’t matter if China’s new J-36 stealth jet is a fighter or a bomber

Despite their similarities, the J-36 likely isn’t a direct copy of the FB-22

To be clear, this is not to say that China simply copied the FB-22 design concept, in much the same way the J-20 itself is not a direct copy of the F-22 despite the oversimplifications you’ll often find on Reddit. Advanced aircraft like the F-22, or the J-20 for that matter, are not one system, but rather a daunting collection of systems married to one another through an airframe and body panels. Like most of China’s new fighter designs, the J-20 did draw extensively from foreign fighters, but not exclusively from any one. Its overall plane form is similar to that of Russia’s defunct MiG 1.44 stealth fighter program, but adorned in low observable design characteristics borrowed directly from Lockheed Martin (as sourced through a Chinese spy convicted of the theft in 2016).

These influences were then blended together with domestically developed design concepts to produce an aircraft that could specifically meet China’s Defense needs, and the J-36 (or whatever it may be called) is almost certainly much the same.

This aircraft all but certainly benefits from stolen intellectual property alongside lasting and concerted Chinese efforts to develop and mature their own aerospace engineering academic infrastructure, resulting in a new aircraft that’s more Chinese than it is anything else.

But by looking at this aircraft through the lens of aviation history, we can clearly see the parallels between China’s new stealth aircraft and American efforts that were shelved two decades ago in favor of freeing up funding for the global war on terror. And now, as China continues to mature their aircraft toward service, the United States will need to look back into its own bag of tricks to find the most effective way to counter this burgeoning capability.

And lucky for Uncle Sam… that old bag is already chock-full of what-ifs like the FB-22. The only obstacle the Air Force needs to overcome is the political will to pull the trigger on a new platform and lines of accounting that come with it.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- 5 of our favorite military nonfiction books (and nearly all are about one branch)

- Video: The big problem that the Air Force’s NGAD has to overcome

- The ships that take Marines to war are in really, really bad shape

- How Army Rangers constantly train in hand-to-hand fighting

- The Air Force’s 2050 report highlights a dark future for air power

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower

Just how good would an F-22/F-35 hybrid fighter really be?

It doesn’t matter if China’s new J-36 stealth jet is a fighter or a bomber

Former Navy SEAL and pioneer combat medicine physician is awarded Presidential Citizen’s Medal

The long list of new stealth jets America has in testing

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page