Game-changing military aircraft that were canceled before they could change the game

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Since the very inception of manned flight, the United States has invested heavily in fielding game-changing military aircraft that leverage cutting-edge technology to provide a tactical or strategic edge over the nation’s peers or competitors. This drive to dominate the skies over the battlefield led the U.S. to field the world’s first military aircraft in 1908, the first aircraft to break the sound barrier in 1947, the world’s first supersonic bomber in 1960, the world’s first manned hypersonic aircraft in 1967, and of course, the world’s first stealth aircraft in 1983… just to name a few prominent blips on the U.S. military aviation timeline.

But for every F-117 that makes it into service, there’s a long list of aviation programs that never quite made it. Sometimes, these efforts leaned too hard into the cutting edge, resulting in capable aircraft that were just too expensive to field in real numbers. Other times, these efforts were built around misconceptions about aviation that, in the days before computer simulations, could only be proven wrong through trial and error.

The existential threats that fueled military procurements throughout the Cold War led to a renaissance in aviation technology. Programs that would never see funding under normal circumstances were suddenly seen as worthwhile ventures in the name of securing any kind of advantage in the nuclear hellfire of a Third World War that, at the time, seemed inevitable to many in power.

Yet, even the massive military expenditures of the Cold War could only fund so many technological revolutions. And some platforms or programs that could have very changed the way mankind perceived airpower were just too expensive, too far-fetched, or too ahead of their time to secure their share of the Pentagon’s coffers, dooming these prototypes, concepts, and X-planes to the secretive confines of America’s sprawling library of military what-ifs.

Here are some of these game-changing programs that never got their chance to actually change the game.

Related: The 5 best fighters America decided not to buy

Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar: A hypersonic space bomber that predates Sputnik

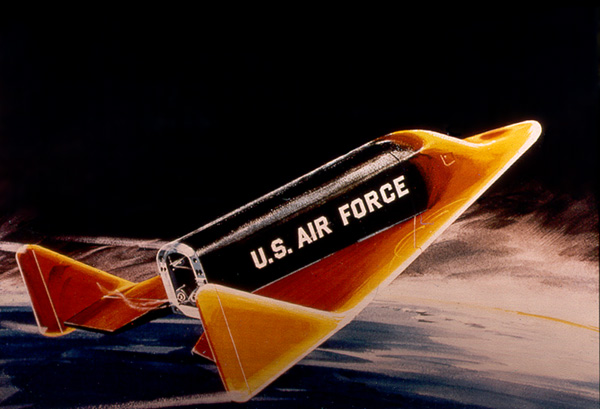

Born out of Germany’s World War II efforts to create a bomber that could attack New York and continue on to the Pacific, Boeing’s X-20 Dyna-Soar was to be a single-seat craft boosted into the sky atop American rockets. That’s right, in the 1950s, the Dyna-Soar would have been the world’s first hypersonic bomber. In fact, the Dyna-Soar was very similar in both concept and intended execution to China’s fractional orbital bombardment system that drew headlines the world over after a successful test in 2021, despite the X-20 program pre-dating the launch of Sputnik 1. So… it’s safe to say this effort was a fair bit ahead of its time.

After launch, the X-20 would soar along the blurred line between Earth’s atmosphere and the vacuum of space, bouncing along the heavens by using a lifting-body design and hypersonic speeds to skip along the upper reaches of the atmosphere. It would circle the globe, releasing its payload over Soviet targets miles below, before making its way back to American territory to come in for a gliding landing, not entirely unlike the Space Shuttle decades later. The X-20 was a 1950s science fiction fever dream born of the nuclear age and the earliest days of the Cold War… and according to experts at the time, it very likely would have worked.

By 1960, the spaceplane’s overall design was largely settled, leveraging a delta-wing shape and small winglets for control in place of a traditional tail. In order to manage the incredible heat of re-entry, the X-20 would use super alloys like the heat-resistant René 41 in its frame, with molybdenum, graphite, and zirconia rods all used for heat shielding on the underside of the craft.

The program was so promising, in fact, that in that same year, the Pentagon tapped a group of elite service personnel to crew this sub-orbital hypersonic bomber. Among them was a 30-year-old Navy test pilot and aeronautical engineer named Neil Armstrong, who would go on to leave the program two years later for even greater heights as a part of NASA’s Gemini and Apollo missions.

Armstrong’s departure was a sign of things to come. After the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the United States saw a pressing need to focus its resources toward orbit itself, canceling this sub-orbital bomber effort to reallocate funds toward new space ventures within America’s fledgling space-fairing organization, NASA.

Related: China’s new hypersonic weapon is a lot like America’s 1950s space bomber

Boeing Quiet Bird: A stealth jet that predates the F-117 by decades

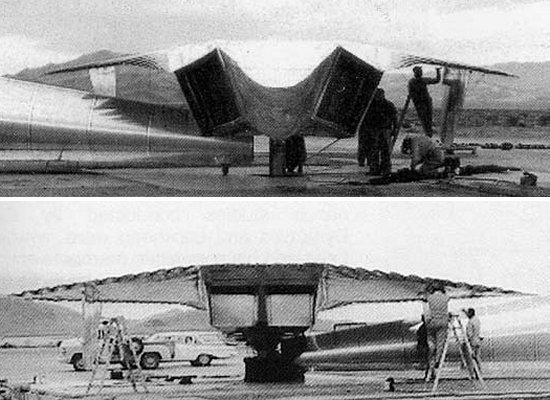

On December 1, 1977, Lockheed’s Have Blue technology demonstrator took flight for the first time, making a significant leap toward fielding the aircraft’s successor, the F-117 Nighthawk, just a few years later. But more than a decade and a half before Have Blue saw a runway, Boeing’s largely-forgotten Model 853-21 Quiet Bird was already making significant strides toward being the world’s first operational stealth aircraft.

While various aircraft have laid dubious claims about being the first to field “stealth” because of design or material happenstance (we’re looking at you, Ho 229), the Quiet Bird effort actually was aimed at developing a low-observable aircraft to serve as an observation plane for the U.S. Army.

Throughout 1962 and ’63, Boeing experimented with stealth aircraft design concepts for the Quiet Bird, incorporating different shapes and construction materials in an effort to reduce the jet’s radar cross section (RCS) long before Denys Overholser at Lockheed’s Skunk Works would develop the means to accurately calculate a design’s radar return without actually building it to stick in front of a radar array. In effect, the Quiet Bird’s stealth development was a very expensive game of guess-and-check.

Although Boeing’s tests did indeed prove promising, the U.S. Army didn’t fully appreciate the value a stealth aircraft could bring to the fight and the program was ultimately shelved. If the Army had been more forward-thinking, the Quiet Bird may have offered a low-observable battlefield reconnaissance platform by the late 1960s, kickstarting the stealth revolution more than a decade earlier and almost certainly changing the way airpower has matured in the decades since.

However, Boeing has credited lessons learned in the development of the Quiet Bird for some of the success they would later find with the AGM-86 Air Launched Cruise Missile.

Related: America’s secret stealth aircraft you’ve never heard of

Convair Kingfish: The high-flying alternative to the Blackbird

When Lockheed’s U-2 spy plane entered service, Soviet air defenses were already capable of tracking the high-flying platform. American officials knew it was only a matter of time before tracking the Dragon Lady turned into targeting it, so, the CIA tasked both Convair and Lockheed with developing a new reconnaissance platform that could fly at higher altitudes, at significantly faster speeds, and have a reduced radar cross-section to minimize the chances of being shot down.

Lockheed would ultimately meet these requirements in their A-12 and subsequent SR-71, but Convair’s Kingfish was its primary competitor until then. Today, Convair’s Kingfish offers us an interesting glimpse into what could have been, if not for the unrelenting genius and budget-mindedness of Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson.

The Kingfish developed out of what remained of Convair’s first attempt, known as the First Invisible Super Hustler or FISH. The FISH would have been carried aloft by a modified B-58 Hustler before being launched and powered by onboard ramjets to speeds in excess of Mach 4. But with concerns about the complexity and cost of the FISH concept, Convair was instructed to go back to the drawing board to come up with a new design built around the Pratt & Whitney J58 “turboramjet” — the same propulsion system Lockheed was working with in their A-12 design proposal.

The resulting Kingfish design was rather forward-leaning for its time, tucking its two J58s deep inside the aircraft’s angular fuselage to limit the radar return they could produce. Its delta-wing design bore a striking resemblance to the stealth aircraft that would follow decades later, but it was that emphasis on stealth that may have ultimately done the Kingfish in.

Pentagon officials, spurred in no small part by criticisms from Lockheed’s legendary Kelly Johnson, feared the Kingfish incorporated too many untested technologies to be built, tested, and operated within the program’s assigned budget. Johnson was outspoken in his views that the Kingfish design compromised performance in favor of stealth — something that was seen as a mistake at the time, despite becoming commonplace in the stealth platforms of today.

Ultimately, Lockheed’s proposal won the day, and the Kingfish was relegated to the what-if file.

Related: America’s YF-12 was an SR-71 armed with air-to-air missiles

McDonnell Douglas/General Dynamics A-12 AVENGER II: A carrier-capable stealth fighter in the 1980s

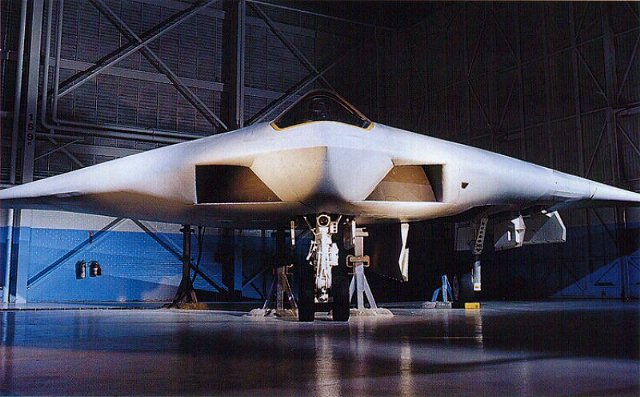

On 13 January 1988, a joint team from McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics was awarded a development contract for what was to become the A-12 Avenger II, not to be confused with Lockheed’s proposed A-12 of the 1960s, which led to the SR-71. Once completed, this Navy A-12 would have been a flying wing design reminiscent of Northrop Grumman’s B-2 Spirit or forthcoming B-21 Raider, though much smaller and with harder angles.

Although the A-12 Avenger II utilized a flying wing design, its overall shape differed from the triangular B-2 Spirit under development at the time for the Air Force. The sharp triangular shape of the A-12 eventually earned it the nickname, “the flying Dorito.“

The A-prefix denoted an attack-emphasis in the A-12 design, but interestingly enough, the aircraft would have actually met the design requirements to be considered a fighter — including an onboard radar array and the ability to carry a variety of air-to-air missiles. As a result, this A-12, carrying an attack prefix, could have been the world’s first true stealth fighter, as the F-117 Nighthawk, secretly already in service, had neither onboard radar nor the ability to engage airborne targets outside the realm of hypotheticals. That’s right, the Air Force’s F-117 wasn’t really a stealth fighter, but the Navy’s A-12 actually would have been.

For some time, it seemed as though the A-12 Avenger II program was going off without a hitch, but then, seemingly without warning, it was canceled by Defense Secretary (and future Vice President of the United States) Dick Cheney in January of 1991. It was only later revealed that the A-12 Avenger II was significantly overweight, over budget, and behind schedule.

Despite a number of other efforts over the years, it would ultimately take 26 more years for the U.S. Navy to get a stealth fighter onto the decks of its carriers in the F-35C.

You can read our full feature on the A-12 Avenger II’s development here.

Related: The Navy is getting serious about its new stealth fighter

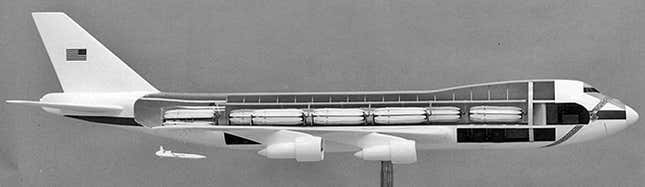

Boeing 747 CMCA: The most cost-effective bomber concept in U.S. history

During the 1960s, the United States began fielding intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in land-based silos, as well as submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) carried by stealthy sub-platforms strategically positioned around the globe. With America’s defense posture primarily oriented toward deterring Soviet aggression, these new methods of delivering nuclear payloads prompted many within the public and politics, to question the need for expensive new bomber development programs. By 1977, this pervasive line of thought took root in the Carter administration, leading to the cancelation of the supersonic heavy payload B-1 bomber effort.

Boeing, recognizing that this cancelation could leave a gap in America’s strategic capabilities, set to work developing an extremely cost-effective bomber-of-sorts to meet this need at a much lower price point. The firm ultimately settled on plans to load a 747 with as many as 72 AGM-86 air-launched cruise missiles carried in nine internal rotary launchers, allowing this commercial people-carrier to serve instead as a long-range arsenal ship capable of wiping out targets from hundreds of miles away. This design, dubbed the 747 Cruise Missile Carrier Aircraft (CMCA), may sound crazy… but it was actually extremely practical in a number of important ways.

With an unrefueled range of 6,000 miles, the ability carry to 77,000 pounds of ordnance, and pre-existing global infrastructure already established for the 747 line, this CMCA concept would have produced the most cost-effective bombing platform in modern history. Today, the B-52 Stratofortress costs approximately $88,000 per flight hour, the B-2 Spirit rings in around $150,000 per hour, and the B-1B Lancer burns through around $173,000 per hour.

The 747 on the other hand, costs just $30,950 per hour to fly, all while carrying a larger payload than any of America’s in-service bombers.

Ultimately, the 747 CMCA never made it off the drawing board, however, with the Reagan administration pulling the B-1 program out of mothballs and the B-2 entering service shortly thereafter – but we may see the U.S. revisit a similar concept in the future. After all, there are already a number of commercial airliners filling other military roles today, from the Boeing 707-based KC-135 to the 747-based E-4B National Airborne Operations Center.

You can read more about the 747 CMCA here.

Related: Why America’s new NGAD fighter could be a bargain, even at $300 million each

Convair NB-36: Delivering nuclear payloads with nuclear-powered bombers

The NB-36 Crusader was an experimental nuclear-powered bomber that actually flew with a nuclear reactor onboard during testing.

The NB-36 was based directly on the absolutely massive Convair B-36 Peacemaker. With a 230-foot wingspan, the B-36 still holds the title for the longest wingspan of any combat-coded aircraft. Its wingspan was so big, in fact, that you could lay a B-52 Stratofortress’ wings over the B-36’s and still have room to throw a Super Hornet on the end for good measure. Thanks to its massive size, the B-36 could fly with an 86,000-pound payload onboard — and in the 1950s, the Air Force experimented with using some of that payload capability to equip the bomber with its own nuclear powerplant — allowing it to fly almost indefinitely like a nuclear-submarine in the sky.

The NB-36 that resulted carried a one-megawatt, air-cooled nuclear reactor that hung on a hook inside its cavernous weapons bay. This reactor then had to be lowered through the bomb bay doors into shielded underground facilities for storage between flights. In theory, a nuclear-powered bomber could stay airborne for weeks at a time (if not longer) and could reach any target on the planet without the need to land or refuel.

At the time, the United States maintained a state of constant readiness in its nuclear-armed bomber fleets to serve as a potent deterrent against Soviet aggression. This policy would later mature in Operation Chrome Dome — an effort that resulted in the U.S. having airborne B-52s armed with nuclear weapons 24 hours a day for eight straight years. As you might imagine, this policy was rather expensive… but it’d get a whole lot cheaper if Uncle Sam didn’t have to pay for fuel.

Rather than using jet fuel, the NB-35’s nuclear reactor would power four GE J47 nuclear-converted piston engines, each generating 3,800 hp, which were then augmented by four additional turbojet engines that produced 5,200 lbs of thrust. The HTRE-3 was a direct-cycle system that pulled air into the compressor of the turbojet and through a plenum and intake that led to the core of the reactor where the air served as coolant. From there, the super-heated air would travel into another plenum that led to the turbine section of the engine before exiting as exhaust out the back.

But despite the effort’s promise, the risks associated with flying a nuclear reactor over American or allied airspace ultimately led it its cancellation in 1961.

Read more about the NB-36 here.

Related: Did America’s next stealth fighter just get revealed on Instagram?

Lockheed X-24C: A scramjet-powered hypersonic aircraft in the 1960s

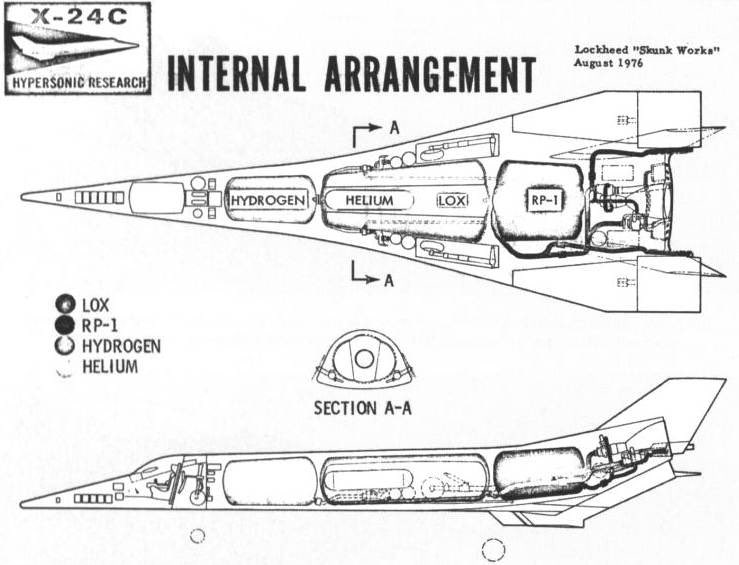

The X-24C was part of an effort to field a scramjet-powered hypersonic research aircraft beginning in the late 1960s. Taking on the role of lead contractor, Lockheed worked side by side with the Air Force’s National Hypersonic Flight Research Facility and NASA to develop and field two hypersonic test aircraft, with each vehicle slated for 100 flights.

The decision was made to equip this new “L-301” program’s aircraft, unofficially dubbed the X-24C, with a new LR-105 rocket engine found at the time in the Atlas series of rockets. The LR-105 would launch and accelerate the X-24C to hypersonic speeds, not unlike the rocket engine that powered the X-15. From there, a second hydrogen-fueled, air-breathing scramjet (supersonic-combustion ramjet) engine mounted on its belly would fire up and take over.

The scramjet engine would propel the X-24C to sustained speeds in excess of Mach 6, reaching intended peak speeds that were higher than Mach 8, or more than 6,130 miles per hour. The aircraft itself resembled the lifting body design leveraged by the Martin Marietta X-24A and B programs that tested unpowered reentry flight characteristics.

In a real way, the L-301 program and its X-24C could be seen as the precursor to ongoing legends about Lockheed Martin’s combined cycle turbofan/scramjet SR-72, the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Mayhem program, and even Hermeus’ combined cycle turbofan/ramjet hypersonic aircraft efforts. Had the X-24C program continued, it would have given the U.S. a scramjet-powered hypersonic aircraft in the 1960s. Instead, the U.S. now appears to still be years away from fielding a reusable, airbreathing aircraft for testing, let alone service.

But by the end of 1977, however, the L-301 program and its notional X-24C were canceled in favor of a different Lockheed developmental effort that would change the value proposition associated with sheer speed. That effort, of course, was Have Blue, which later matured into the F-117 Nighthawk.

You can read more about the X-24C here.

Read more from Sandboxx News

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Breaking News, Military History

How US Special Forces took on Wagner Group mercenaries in an intense 4-hour battle

F-16s carrying the A-10’s 30mm cannon actually saw combat

How does China’s new J-35 stealth fighter compare to America’s F-35?

Why China’s new J-35 jet could mean trouble for America

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page