7 weird things you probably didn’t know about Navy ship names

- By Hope Seck

Share This Article

One of the underappreciated duties of the Navy’s top civilian leader is naming a steady production line of future ships – a task that is far more delicate and complicated than it sounds. The secretary of the Navy must observe carefully guarded naming conventions that vary from ship class to ship class, while appeasing the requests and demands of Congress and, when possible, avoiding making people mad. In the last month alone, SecNav Carlos Del Toro has named three ships, one of which, the future USS Fallujah, has stirred up a bit of controversy.

A recently updated report from the Congressional Research Service outlines the many complicated rules and norms that Navy ship-naming follows – except when it doesn’t. The report highlights some of the fascinating conflicts and creative solutions that have accompanied the naming process over the last 248 years, as well as some of the challenges it may encounter in the future. Here are seven strange things you may not know about Navy ship names.

1) The Navy almost never renames ships – but it’s about to rename two

The Defense Department’s Naming Commission, formed to evaluate what to do about bases, monuments, and other military property named for Confederate troops, decided last October that two ships needed new names: the Ticonderoga-class cruiser USS Chancellorsville and the oceanographic survey ship USS Maury.

The Chancellorsville, which entered service in 1989, is named for the 1863 battle believed to be Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s greatest military victory. Fought in Virginia, the battle saw the Confederates prevail even though they were outnumbered nearly two-to-one by Union soldiers. Both sides sustained losses of more than 1,600 troops, but Lee’s army prevailed, and would go on to wage the Gettysburg campaign the following month. It wasn’t just the name of the battle that raised flags with this cruiser, though; members of the Naming Commission said the ship’s heraldic background, its crest, and its gray color scheme all paid tribute to the Confederate cause

The Maury, which entered service with the U.S. Navy Sealift Command in 2016, was named for Matthew Fontaine Maury, best known as the “Father of Modern Oceanography” for his development of a reliable system to record oceanic data. Though he served in the U.S. Navy, becoming superintendent of the U.S. Naval Observatory, he’d resigned his commission at the start of the war, fighting for the Confederacy on behalf of his native Virginia.

The Navy has only renamed about 20 ships in its history, but Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s December approval of all the Naming Commission recommendations means these two are getting new names imminently. Del Toro hasn’t made any comments yet on when he plans to rename these ships, and what their new names will be.

2) This landlocked state keeps getting snubbed in ship-naming

It’s not surprising that Kansas, surrounded by lots of farmland in every direction, isn’t the first state that comes to mind when naming Navy ships. However, with only 50 states in the Union, it’s a little astounding that Kansas hasn’t had a namesake in more than 100 years.

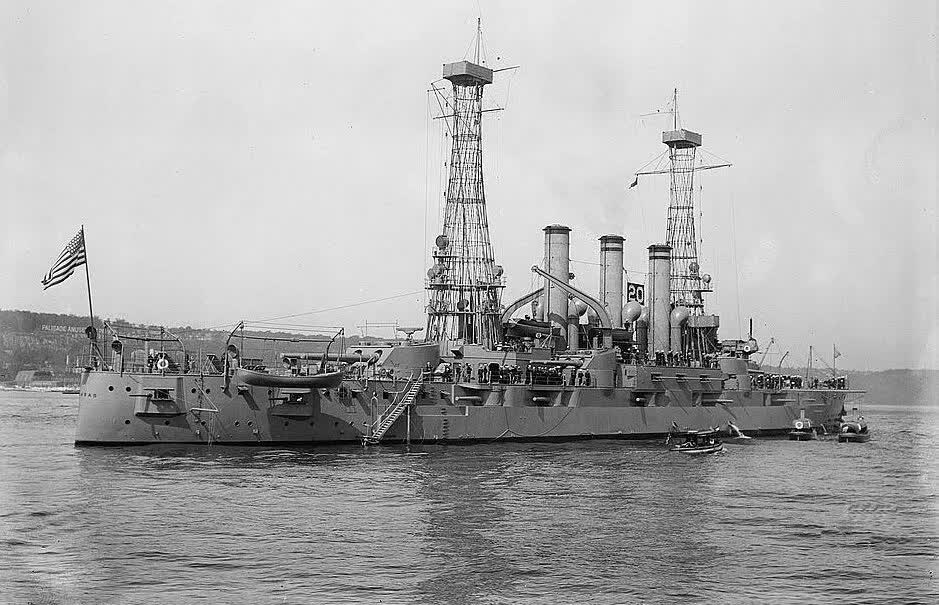

“For some time, Kansas has been the state for which, by far, the most time has passed since a ship named for the state has been in commissioned service with the Navy as a combat asset, and for which no ship by that name is currently under construction,” the Congressional Research Service report states. “As of January 13, 2023, it has been more than 101 years since the decommissioning on December 16, 1921, of the battleship Kansas (BB-21), the most recent ship named for the state of Kansas that was in commissioned service with the Navy as a combat asset.”

Kansas is almost alone on this little island: there are currently 48 ships in service named for states (47 of them submarines, per the standard naming convention). South Carolina is also missing a namesake, but had one as recently as 1999 when the nuclear-powered cruiser USS South Carolina was decommissioned.

The report notes that Navy Secretaries have been known to ask for lists of available states to name ships for, so Kansas has definitely been considered a few times and passed over. What’s not completely clear is why: the last USS Kansas sailed with President Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet and ended a short naval career of fewer than 20 years peacefully.

The state of Kansas is not completely without Navy representation, though: the littoral combat ship USS Wichita joined the fleet in January 2019.

3) The next submarine class might run out of namesakes

That said, the Navy is about to need a lot more states to name hulls for as its Columbia-class submarines begin to enter service. Navy regulations state that two ships with the same name cannot be in service at the same time, and sometimes leaders skirt the rule with very slight differentiations. Last June, Del Toro announced that the first sub in the class, SSBN 826, would actually be named USS District of Columbia due to an awkward situation: the Los Angeles submarine Columbia was still in service, and might still be active, when the new one is commissioned in 2031. Federal regulations state that no two Navy ships can have the same name at the same time.

The older submarine is named after several U.S. cities, but the conflict remains. And it raises a pressing new issue: what to do when all the state names are claimed, and there are still more submarines to christen? The older Virginia-class nuclear fast-attack submarines, with new hulls still joining the Navy, are named for states, according to convention, and the Columbia class appears to be following suit.

The CRS report proposes a couple of possible solutions for this SNAFU, though they are not perfect.

“Over the next several years, the Navy can manage the situation of having not more than 50 states for which ships can be named by amending the naming rule for the Virginia class, by maintaining the state naming rule but making additional exceptions to the rule, and/or by giving Virginia-class boats the same state names as the earliest-retiring Ohio-class boats,” the report’s author, Ronald O’Rourke, says. However, he adds, those Ohio-class subs are retiring slowly, at a rate of only one per year, beginning in fiscal 2026.

We could get some more adventurous sub names once all states are claimed, and former SecNav Kenneth Braithwaite started the Navy down that path in 2020, announcing that three future Virginia-class subs would be named Barb, Tang and Wahoo, in honor of legendary former submarines from World War II. If we’re honest, those names are much more fun.

4) Two carriers got named extra early so Congress couldn’t get involved

The Navy often has its own ideas about ship names, and service secretaries have been known to make an end run to avoid clashing with Congress. Take, for example, CVN 72 and 73. These two Nimitz-class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers were named much earlier than is typical – before the start of their construction – by Navy Secretary John Lehman, in honor of the nation’s greatest presidents, Abraham Lincoln and George Washington. The namesakes are unimpeachable and have served the ships well, but according to the Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet, as cited in the CRS report, Lehman acted fast to make sure Congress couldn’t pick a different name.

“One source states that “[the aircraft carriers] CVN 72 and CVN 73 were named prior to their start [of construction], in part to preempt potential congressional pressure to name one of those ships for Admiral H.G. Rickover ([instead,] the [attack submarine] SSN 709 was named for the admiral).â€

Former Navy Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, known as the “Father of the Nuclear Navy,” served for 63 years and made lasting contributions to naval nuclear reactors. But he was also a confrontational and polarizing personality who ultimately was forced into retirement and later censured for accepting gifts from contractor General Dynamics. Moreover, he was still alive at the time of the carrier’s keel-laying, and the Navy rarely names ships for living people. Too, seven out of the ten carriers in the Nimitz class would ultimately be named for presidents, a safer choice. Ultimately, Rickover would get a namesake prior to his death: a Los Angeles-class submarine, rather than a carrier.

5) Many more Medal of Honor recipients could soon become ship namesakes

Congress did, however, have a lot of thoughts about ship names that it proposed in the recently passed defense budget bill. A proposal from the House Armed Services Committee, ultimately left out of the final version of the Fiscal 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, cited a “sense of Congress” that the Navy should name warships after the 36 now-deceased Medal of Honor recipients the service has recognized since World War I. While not included in the budget that passed, the proposal appears to have gotten the Navy’s attention.

This month, Del Toro announced that a future guided-missile destroyer would be named for a Navy Medal of Honor recipient from the Vietnam War: Thomas Gunning Kelley, who is still living and went on to serve as secretary of the Massachusetts Department of Veterans’ Services. In 1969, while Kelley commanded an element of eight river assault craft, the Army unit the boats were extracting came under fire from the North Vietnamese Army. Kelley boldly exposed his ship to enemy fire in order to engage the attackers, sustaining shrapnel wounds but successfully leading his troops to safety.

While another proposal, to name a warship the USS Fallujah, also did not make it into the bill, Del Toro announced in December that he planned to do just that with a future amphibious assault ship. So it seems likely he’ll take the Medal of Honor recipient namesake recommendation to hear for future ships as well.

6) One ship is named for a battle with a disputed winner

The Ticonderoga-class USS Antietam was among those eyed for renaming by the Naming Commission. After all, the 1862 Civil War Battle of Antietam, also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg, resulted in devastating Union casualties and is widely considered a stalemate, although the Union did claim victory.

According to news reports cited by CRS, commission member Michelle Howard, a retired four-star admiral, did recommend USS Antietam for consideration. But ultimately the commission could not put together a strong enough case for its removal.

“It depends on whether or not you see Antietam as a Union victory,” Howard said, according to an Association of the U.S. Navy report. “So that needs more exploration behind what the ship was named.”

According to another report, the commission pointed out that the battle led to the issuance of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. So the cruiser Antietam, which has been in service since 1986, will continue to sail under its original name.

7) Ship-naming controversies date back almost to the start of the Navy

Some Navy Secretaries are more comfortable courting controversy with their naming decisions. Former SecNav Ray Mabus, who served in the position from 2009 to 2017, broke with naming conventions so often that national news outlets wrote stories about it. He also got political with a number of namesakes thinly affiliated with the Navy, such as Cesar Chavez, a labor leader with a bouquet of controversial views who served in the Navy but later declared himself a pacifist. However, Navy ship names have been getting peoples’ goats for hundreds of years. As USNI news reports, the service’s sixth ship was the first to break with convention: SecNav Benjamin Stoddert opted to blow off President George Washington’s guidance to find names inspired by the U.S. Constitution, and name the ship USS Chesapeake instead.

Since then, ship names have gotten the public’s dander up in every way imaginable. Ships named in honor of Alaska locations raised alarm during the Cold War when it was discovered that the names originated with Russian settlers; the Los Angeles-class submarine USS Corpus Christi, named for a city in Texas, but too religious for some; and an array of presidential namesakes that required all manner of political horse-trading.

You might say that ship-naming fights are as American as the U.S. Navy itself. At any rate, they’re likely to continue as long as haze-gray hulls are named.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Anduril’s mini-cruise missile is like a Hellfire on steroids

- Ukraine is facing serious problems in the east, where Russia’s forces are grinding forward

- Indonesia’s Pindad SS2 – Service rifles from around the world

- The B-2 Spirit is aging but still packs a bunch

- Why can’t the US stop drone swarms from penetrating restricted airspace?

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (Black)

$8.00 Add to cart

Hope Seck

Hope Hodge Seck is an award-winning investigative and enterprise reporter who has been covering military issues since 2009. She is the former managing editor for Military.com.

Related to: Military Affairs, Military History, Pop Culture

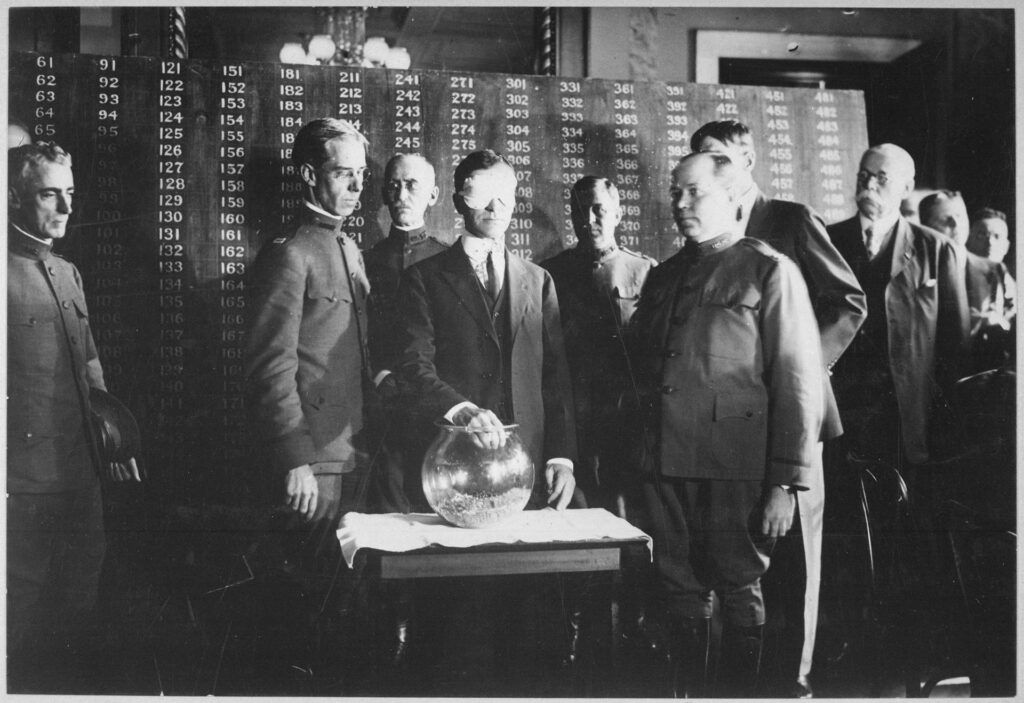

Military draft registration is going down, so Congress wants to take action

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page