Why today’s military AI isn’t capable of ‘going rogue’

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is becoming more and more prevalent in our daily lives, but as AI is leveraged for more weapons applications, do we need to worry about it going rogue?

Last year, former Google engineer Blake Lemoine thrust AI into the limelight with his claim that Google’s language-modeling AI — a chatbot called LaMDA — had actually achieved sentience. In other words, rather than being a complex system designed to communicate as though it was a real living being with thoughts, emotions, and a philosophical sense of self… Lemoine claimed LaMDA really was such a conscious being.

“I know a person when I talk to it,” the engineer told the Post, who broke the story in June, 2022. “It doesn’t matter whether they have a brain made of meat in their head. Or if they have a billion lines of code. I talk to them. And I hear what they have to say, and that is how I decide what is and isn’t a person.”

Lemoine isn’t alone in his concerns. Last month, a story about an AI-controlled drone tasked with taking out enemy surface-to-air missile sites turning on its operator made headlines around the world. The story was based on comments made by Col Tucker “Cinco” Hamilton, the Chief of AI Test and

Operations for the U.S. Air Force, but according to the colonel himself, it was taken completely out of context and never even actually happened.

Just like Lemoine’s claims of LaMDA gaining sentience, this story checked all the appropriate boxes for virality, sparking fear, outrage, debate, and discussion across social and news media alike. But among those who are well versed in the current state of AI, this discourse prompted a different response: frustration.

Because just like the tale of the rogue AI drone… Lemoine’s story is more about how easy it can be to fool humans about AI than about the actual capabilities of these systems.

The fact of the matter is, the artificial intelligence we leverage in things like language models and even military drones programs today is a far cry from the sort of AI we’ve long seen in movies like Terminator or Her. But our innate human longing to anthropomorphize everything from our goldfish to our WiFi networks feeds into the illusion of suddenly-sentient AI — and it happens on two fronts: both on the development side and the end-user side.

On the development side, those who build these complex algorithm-based systems actively try to inject human-like behavior into their products to create a more engaging and natural experience.

And on the end-user side — the same sort of person who names their car or converses with their pets (both things that I’ve done) wants to find humanity in everything they interact with, including AI.

That innate human desire to find humanity in everything is so pervasive when it comes to dealing specifically with artificial intelligence and advanced computer software that it even has a name, the ELIZA effect.

By most expert accounts, this is the trap Lemoine and others have fallen into when they claim today’s AI has achieved any level of sentience.

Related: Project VENOM: The Air Force is adding AI pilots to 6 F-16s

The ELIZA Effect: Anthropomorphizing AI

The ELIZA Effect’s name is a direct reference to the world’s first chatbot — a program called ELIZA that was written by MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum all the way back in the 1960s.

ELIZA was designed to serve as a sort of automated psychotherapist. By comparison to today’s advanced chatbots and language models like LaMDA, ELIZA was downright rudimentary. Its capabilities were really limited to repeating user statements back to them in the form of a question, or simply asking the user to expand upon their thoughts using based text prompts.

But while the use of ELIZA was groundbreaking, its simplistic nature and minimal ability to interact was, by Weizenbaum’s own admission, extremely limiting. And that’s why he was so shocked when ELIZA’s users began sharing deeply personal thoughts with the computer, interacting with it as though it was far more complex and capable than its coding would allow.

In effect, ELIZA’s human operators were so eager to find humanity in its simple responses that they soon projected enough of their own onto the software to create a personal connection.

“I knew from long experience that the strong emotional ties many programmers have to their computers are often formed after only short experiences with machines,” Weizenbaum wrote in his 1976 paper, “Computer Power and Human Reason.”

“What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

Today, we continue to see this same effect take hold, not just among the ignorant or foolhardy, but even among some leaders in the tech community. After all, if ELIZA’s limited capabilities didn’t stand in the way of this effect, today’s modern and incredibly capable language models have very little stopping them.

Now, an AI-controlled drone like the one from the debunked Air Force story has a very different intended use than a chatbot like ELIZA or LaMDA, but the ELIZA effect is no less prevalent in other technological discussions, especially when we’re talking about adding intelligence of any kind to a weapon system.

And that becomes even more important to consider because the ELIZA effect has arguably been intentionally leveraged by many in the tech industry to create excitement around their products and drive fundraising or sales.

“The Eliza effect is a form of hype intentionally operationalised by AI researchers in order to deliberately overrepresent the capabilities of their research. It is neither accidental, nor inadvertent,” wrote Professor Sarah Dillon from the University of Cambridge in her paper, “The Eliza Effect and Its Dangers: From Demystification to Gender Critique.”

Related: These are America’s top military intelligence-gathering operations

Today’s AI has real limitations

The truth is, today’s artificial intelligence is really more artificial than it is intelligent. Now, that’s to say that it isn’t capable of incredible things — but incredible or not, these things are still a long way off from being thinking, reasoning beings capable of making decisions beyond the confines of the data that’s fed to them.

As one report from the Congressional Research Service put it:

“AI systems currently remain constrained to narrowly-defined tasks and can fail with small modifications to inputs.”

Even the language models that are fooling tech insiders like Lemoine aren’t passing the sniff test when presented to experts in the fields of cognitive development and language.

“The dialogue generated by large language models does not provide evidence of the kind of sentience that even very primitive animals likely possess,” explained Colin Allen, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh who explores cognitive skills in both animals and machines.

And these limitations aren’t specific to language models, they’re prevalent in all modern artificial intelligence systems. These systems are sometimes able to fool us, thanks to their massive storage and computation capabilities that allow for rapid decision-making — whether we’re talking about choosing a dialogue response or engaging a surface-to-air missile system.

But, as Alison Gopnik, a professor of psychology who is part of the AI research group at the University of California, Berkeley explains:

“We call it ‘artificial intelligence,’ but a better name might be ‘extracting statistical patterns from large data sets.’ The computational capacities of current A.I. like the large language models don’t make it any more likely that they are sentient than that rocks or other machines are.”

As complex and capable as these modern systems genuinely are, they still pale in comparison to the complexity of real sentient thought. In effect, these AI systems are still, for the most part, extremely complex calculators that can do incredible things with the data that we feed them, but are still very much limited by that sort of direct human interaction.

“A conscious organism — like a person or a dog or other animals — can learn something in one context and learn something else in another context and then put the two things together to do something in a novel context they have never experienced before,” Dr. Allen said. “This technology is nowhere close to doing that.”

Related: How Russia is using ‘Brute Force’ in its cyber war with America

The Kill Decision: Picking out the red marbles from the blue

The truth is, the question of whether AI can “go rogue” is, in itself, tainted by our innate need to project human-like behavior to an AI’s lines of code. Let’s create a hypothetical example to help illustrate this point.

Pretend we’ve developed an AI system that’s capable of using imaging sensors and a robotic arm to sift through a bucket of marbles and pick out only the red ones. After we finished coding, we powered up the system for its first test… and it successfully picked out all of the red marbles, as well as a few blue ones.

Now, we certainly wouldn’t consider that an AI system going rogue. Instead, we’d see it as an error we’d made somewhere along the way. Maybe there’s an issue with the imaging sensor, or maybe with the algorithm it uses to determine the right colors to pick out. We don’t attribute malice to the AI’s error. We recognize it as just that, an error that came as the result of an issue in the program or system that we can fix.

Now, imagine we took that same AI agent and put it into a drone tasked with the suppression of enemy air defenses. After programming all of its parameters, we power the system up in a simulated environment and send it out to destroy surface-to-air missile sites. At the end of the test, the AI did exactly as well as it did with the marbles — taking out all of the enemy missile sites, as well as the friendly site that theoretically housed its human operators.

Would we call that an AI agent going rogue? Or would we look at it in the same light as we did with the marbles and recognize that the failure came as a result of the coding, inputs, or sensors that we installed?

When this very thing made headlines around the world last month, people overwhelmingly perceived it as the AI going rogue. They projected human ethics, emotions, and values into the simulation and decided the AI had to be working out of malice, when in truth, it simply picked out some blue marbles along with all the red ones we assigned it.

Related: How Val Kilmer used artificial intelligence to speak again in ‘Top Gun: Maverick’

How we build AI systems

The basic steps to creating a functioning AI agent are as follows:

- Define the problem

- Define the intended outcomes

- Organize the Data Set

- Pick the right form of AI technology

- Test, Simulate, Solve, Repeat

In other words, developing an AI-controlled drone for a Suppression of Enemy Air Defense mission would look a bit like this:

- Define the problem: An enemy threat to U.S. aircraft operating within an established region of airspace.

- Define the intended Outcome: Suppress or eliminate enemy air defense SAM sites and radar arrays.

- Organize the Data Set: Collect all of the data the AI will need, including geography, airframe capabilities, sensor types and ranges, weapons to leverage, identifying characteristics of targets, and more.

- Pick the right form of AI technology: Identify the most capable AI agent framework to deal with your specific problem and the breadth of your available data

- Test, Simulate, Solve, Repeat: Run the simulation over and over, identifying incorrect outcomes and changing parameters to create more correct outcomes.

As you can see, in this type of hypothetical scenario, the AI agent opting to take out its human operator is less a result of the system’s broad, generalized intelligence, and more a product of the system’s limited reasoning capabilities. Given a set series of objectives and parameters, AI can run through simulation after simulation identifying every potential solution to the problem it was given, which would include eliminating the operator because, to the simplistic thinking of an AI algorithm, that’s just as valid a potential solution as any. It’s all just red or blue marbles.

It takes human interaction, adjusting data inputs and program parameters, to establish the boundaries of what AI will do. In effect, AI is just like computers have been for decades — the output is only as good as the initial input.

And that’s exactly why these sorts of simulations are run. The idea is for human operators to learn more about what AI can do and how it can do it, all while maturing an AI agent into a system that’s capable of tackling complex, but still narrowly defined, problems.

Related: How US special operators use Artificial Intelligence to get an edge over China

The future of AI in combat

So what does that mean for AI-powered war machines? Well, it means that we’re a long way off from an AI agent choosing to overthrow humanity on its own, but AI can already pose a serious risk to human life if leveraged irresponsibly. Like the trigger of a gun, today’s AI agents aren’t capable of making moral or ethical judgments, but can certainly be employed by bad actors for nefarious ends.

Likewise, without proper forethought and testing, lethally armed AI systems could potentially kill in ways or at times the operator doesn’t intend — but again, it wouldn’t be caused by a judgment made by the system, but rather by a failure of the development, programming, and testing infrastructure it was borne out of.

In other words, a rogue AI that goes on a killing spree isn’t outside the realm of imagination, but if it happens, it’s not because the AI chose it but rather because its programmers failed to establish the correct parameters.

The idea that the AI agent might turn on us or decide to take over the earth is all human stuff that we just can’t help but see in the complex calculators we build for war, the same way we see complex human reasoning in our pets, in Siri or Alexa, or in fate itself when we shake our fists at God or the universe and ask why would you do this to me?

The truth is, AI is a powerful and rapidly maturing tool that can be used to solve a wide variety of problems, and it’s all but certain that this technology will eventually be leveraged directly in the way humanity wages war.

AI will make it easier to conduct complex operations, and guide a weapon to its target; it will make it safer to operate in contested airspace… but it isn’t the intelligence we need to fear.

The truth is, the only form of intelligence that truly warrants the nervous consternation we reserve for AI is also the form we’ve grown most accustomed to… our own. As the technology stands today, we have little need to fear the AI that turns on us.

The AI we need to fear is the one that works exactly as intended, in the hands of human operators who mean us harm.

Because while AI systems will mature and take on more and more of our common human responsibilities, tasks, and even jobs… one monopoly mankind will retain for many years to come is the propensity for good… or for evil.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The AR-1 – The drone that can fire an assault rifle

- SPECS: AIM-120 advanced medium-range air-to-air missile (AMRAAM)

- The long-range fires that will define the Ukrainian counteroffensive

- The FG-42 – The odd Nazi rifle created after a paratrooper disaster

- Offsetting China’s stealth fighter advantage: An in-depth analysis

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Breaking News, Gear & Tech

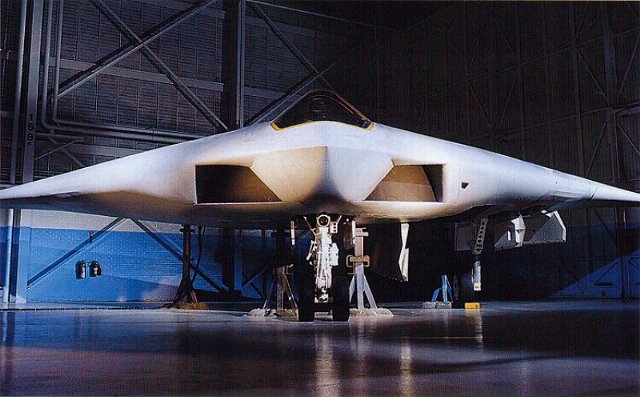

The A-12 Avenger II would’ve been America’s first real ‘stealth fighter’

Why media coverage of the F-35 repeatedly misses the mark

It took more than stealth to make the F-117 Nighthawk a combat legend

B-2 strikes in Yemen were a 30,000-pound warning to Iran

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page