The complete list of US hypersonic missile tests, successes and failures

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

The United States conducted a total of 21 publicly disclosed hypersonic missile tests between April 2010 and July 2022. Of those 21 tests, 10 were deemed successful, with three partial successes, and eight total failures.

Of those 10 successful tests to take place over the past 12 years, no fewer than half of them came over the last 11 months, as the U.S. stepped up its hypersonic efforts in the face of new weapons being fielded by near-peer competitors in China and, to a lesser extent, Russia.

Hypersonic missiles, or weapons that fly and maneuver at speeds in excess of Mach 5, are considered practically unstoppable for even the most advanced air defense systems, making their development a priority for a number of nations in recent years.

Today, only Russia and China have hypersonic missiles in active service, with the United States working toward matching the capability. As a result, there’s been a great deal of discussion about America’s hypersonic failures, juxtaposed against competitor successes. However, the truth is, perceptions of this competition have been shaped as much by each respective nation’s level of transparency as actual technological progress.

Put simply, the United States—while secretive at times—has been far more open about its hypersonic efforts, announcing failures as well as successes when they occur. Neither Russia nor China publicly discloses failures from within their high-level defense programs at large, making direct comparisons difficult. The U.S. may be lagging in terms of timeline, for instance, but America’s successes in the realm of scramjet propulsion for hypersonic cruise missiles, an approach no nation has managed to field thus far, would suggest that its efforts are, at least in some cases, more technological mature than systems being fielded by its competitors.

So, while America’s hypersonic efforts have met with setbacks, the truth is that setbacks are par for the course… and with a number of high-profile successes over the past 11 months, the United States may be positioned to win the real hypersonic arms race: not the race to be first, but the race to field the most effective systems.

Related: Is the US really losing the hypersonic arms race?

The modern hypersonic missile race began with a speech

In March of 2018, Russian president Vladimir Putin delivered a speech that would come to be known as the onset of the modern hypersonic missile race. During his state-of-the-nation address, Putin outlined a number of new missiles that he claimed would render the world’s air defense systems useless, including the Kh47M2 Kinzhal, which he touted as already in service, and the Avangard boost-glide system that would join it the following year.

“Sarmat is a formidable missile and, owing to its characteristics, is untroubled by even the most advanced missile defence systems,” Putin said of the nation’s newest nuclear ICBM.

“But we did not stop at that. We started to develop new types of strategic arms that do not use ballistic trajectories at all when moving toward a target and, therefore, missile defence systems are useless against them, absolutely pointless.”

In 2019, China followed in Russia’s footsteps, placing their own hypersonic boost-glide anti-ship missile into service, known as the DF-ZF. Since then, no nation has managed to field another operational modern hypersonic weapon, though efforts remain ongoing in laboratories spanning from Australia to Brazil. In the United States, there are now more than 70 ongoing hypersonic development programs drawing funds from the Pentagon’s budget, though Uncle Sam has yet to cross the barrier between weapons in testing, and weapons in service.

Here at Sandboxx News, we’ve covered the global race to field modern hypersonic missile systems, as well as the geopolitical tomfoolery that’s accompanied it, at length. If you’d like to catch up on the hypersonic game, here are some good places to start:

Links to learn more about the hypersonic missile race:

- Is the US really losing the hypersonic arms race?

- American hypersonic weapons in development

- Russian and Chinese hypersonic weapons

- What makes hypersonic missiles special?

- What’s the difference between Boost-glide and Scramjet?

- The problems with hypersonic missiles

America’s hypersonic missile tests and outcomes to date

| Date (Approx) | Weapon | Type | Outcome |

| 4/22/2010 | Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2) | Boost-Glide | Partial Success |

| 5/26/2010 | Boeing X-51 Waverider | Scramjet | Success |

| 7/29/2010 | Hypersonics Flight Demonstration program (HyFly) | Scramjet | Failure |

| 3/24/2011 | Boeing X-51 Waverider | Scramjet | Partial Success |

| 8/11/2011 | Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2) | Boost-Glide | Partial Success |

| 11/17/2011 | Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) | Boost-Glide | Success |

| 8/14/2012 | Boeing X-51 Waverider | Scramjet | Failure |

| 5/1/2013 | Boeing X-51 Waverider | Scramjet | Success |

| 8/25/2014 | Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) | Boost-Glide | Failure |

| 10/30/2017 | Common Hypersonic Glide Body (FE-1) | Boost-Glide | Success |

| 3/19/2020 | Common Hypersonic Glide Body (FE-2) | Boost-Glide | Success |

| 12/2020 | Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) | Scramjet | Failure |

| 4/5/2021 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Failure |

| 5/1/2021 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Success |

| 7/28/2021 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Failure |

| 9/2021 | Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) | Scramjet | Success |

| 10/21/2021 | Common Hypersonic Glide Body (FT-3) | Boost-Glide | Failure |

| 12/15/2021 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Failure |

| 3/2022 | Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) | Scramjet | Success |

| 5/14/2022 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Success |

| 6/1/2022 | Common Hypersonic Glide Body | Boost-Glide | Failure |

| 6/29/2022 | Operational Fires (OpFires) | Boost-Glide | Success |

| 7/12/2022 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Success |

| 7/18/2022 | Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) | Scramjet | Success |

| 12/9/2022 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Not Disclosed |

| 1/30/2023 | Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) | Scramjet | Success |

| 3/13/2023 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Failure |

| 8/19/2023 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Not Disclosed |

| 10/12/2023 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Not Disclosed |

| 12/9/2023 | AGM-183A ARRW (Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon) | Boost-Glide | Success |

Related: American hypersonic weapons in development

Hypersonic missile testing in the US has been slow

Despite all the talk about hypersonic missiles in the media, the United States has been rather slow to test these weapons. With just 21 tests over 12 years, America has averaged a bit less than two launches per year, despite rapid advances made by competitors in Russia and China.

There are good reasons for this slow progress, however. Historically speaking, the United States has led the world in hypersonic research. The U.S. launched the first hypersonic vehicle, flew the first crewed hypersonic aircraft, and even had plans for a hypersonic bomber in development before the Soviets launched Sputnik. These hypersonic efforts continued into the 21st century with NASA’s hypersonic X-43 and Boeing’s X-51 racking up successes — and records — through 2013.

The truth is, hypersonic flight isn’t particularly rare. It was common for the Space Shuttle, for instance, and practically all ballistic missiles, to achieve hypersonic speeds. What makes modern hypersonic missile platforms so dangerous isn’t their speed alone, but rather, their speed coupled with maneuverability. It’s the ability to change course at these extreme velocities that makes tracking and intercepting a modern hypersonic missile so difficult. But building a weapon that can achieve this feat is also incredibly expensive, requiring specialized equipment and facilities throughout development and testing. America’s hypersonic testing infrastructure is simply too thin to support rapid development and testing — there is only one wind tunnel in the nation, for instance, that can support hypersonic speeds and it belongs to NASA.

The Pentagon has already begun allocating money to improve upon America’s testing infrastructure, however, and it seems likely that the nation’s progress in this arena will continue to speed up as the testing bottleneck created by limited access to facilities loosens.

It’s also very important to note that, while the United States does report its hypersonic failures as well as its successes, the same can’t be said for Russia or China. Neither nation has publicly offered up figures regarding testing success rates for their hypersonic weapons, preferring instead to only disclose their successes.

Read more from Sandboxx News

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower

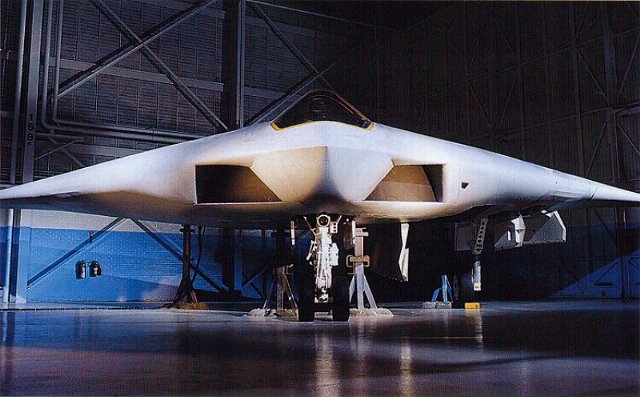

The A-12 Avenger II would’ve been America’s first real ‘stealth fighter’

Why media coverage of the F-35 repeatedly misses the mark

It took more than stealth to make the F-117 Nighthawk a combat legend

B-2 strikes in Yemen were a 30,000-pound warning to Iran

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page