- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

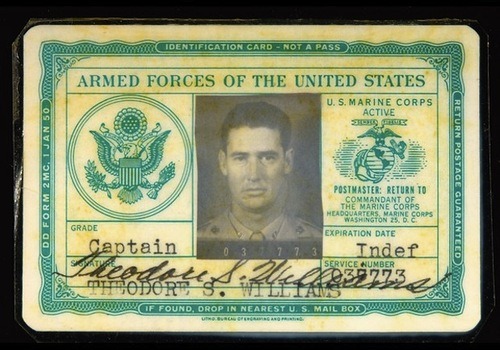

Ted Williams was selected professional baseball’s Most Valuable Player in 1946 and 1949 and played on American League All-Star Teams 16 times (1939-42, 1946-49, 1951, 1953 and...

Ted Williams was selected professional baseball’s Most Valuable Player in 1946 and 1949 and played on American League All-Star Teams 16 times (1939-42, 1946-49, 1951, 1953 and 1955-58). He still holds the sixth-best all-time batting average and is second only to Babe Ruth in slugging percentage. He is the oldest man to win a batting title (in 1958 at age 40). The Sporting News named him the Player of the Decade, no small achievement when one looks at his competition: Joe DiMaggio, Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle.

With Williams earning accolade after accolade, what team did he believe was the best that he was ever involved with? Was it the Boston Red Sox, which he joined in 1939, or the Texas Rangers which he later managed? Perhaps it was the MLB All-CenturyTeam or even the MLB All-Time Team?

Surprisingly, none of these teams were selected by Williams. When asked to name the greatest team he was ever on, Ted Williams replied without hesitation, “The US Marines”.

After the 1942 season Williams voluntarily enlisting in the Navy reserve and was called to active duty in November of that year.This marked the first of two major career disruptions for military service. He eventually would lose almost four years of playing time at the very peak of his career.

Naval aviation cadet T. S. Williams was sent to Amherst College in chilly Massachusetts for preflight training, a 90-day ordeal described as a combination of Officer Candidates School and a crash course in advanced science. Prospective pilots got into shape and learned how to be military officers as they studied basic theories of how airplanes operated. The surviving cadets then moved to Chapel Hill, N.C., for three months of preflight training. There the academic load became more rigorous, but they actually got to fly. The ground-school curriculum included subjects such as engines, ordnance, aircraft characteristics, aerodynamics and navigation.

Upon graduation, Williams opted for the Marine Corps and was commissioned a second lieutenant. He then moved south to Pensacola, Fla., for advanced flight training as a fighter pilot. It was there that he learned to fly the propeller-driven, single-engine, single-seat Vought F4U Corsair, the famous bent-wing “U-Bird,” a favorite mount of Marine aces in the South Pacific.

Although he was discharged in late 1945 without being called into active combat, he was called from the inactive reserves in 1953 to fight in the Korean War. In Korea, William’s squadron leader was to become widely known. His leader being John Glenn, who became an astronaut and a senator after the War.

“By luck of the draw, we went to Korea at the same time,” Glenn said. “We were in the same squadron there. What they did at that time, they teamed up a reservist with a regular to fly together most of the time just because the regular Marine pilots normally had more instrument flying experience and things like that. So Ted and I were scheduled together. Ted flew as my wingman on about half the missions he flew in Korea.”

This wasn’t a goodwill tour and was involved in a lot of combat. He got hit on several occasions, managing to escape death each time.

One such incident occurred when Williams was flying an air strike on a troop encampment near Kyomipo. Williams’ F-9 was hit by hostile ground fire. He commented later: “The funny thing was I didn’t feel anything. I knew I was hit when the stick started shaking like mad in my hands. Then everything went out, my radio, my landing gear, everything. The red warning lights were on all over the plane.” The F-9 Panther had a centrifugal flow engine and normally caught fire when hit. The tail would literally blow off most stricken aircraft. The standard orders were to eject from any Panther with a fire in the rear of the plane. His aircraft was indeed on fire, and was trailing smoke and flames. Glenn and the other pilots on the mission were yelling over their radios for Williams to get out. However, with his radio out, Williams could not hear their warnings and he could not see the condition of the rear of his aircraft. Glenn and another Panther flown by Larry Hawkins came up alongside Williams and lead him to the nearest friendly airfield. Fighting to hold the plane together, he brought his Panther in at more than 200-MPH for a crash landing on the Marsden-matted strip. With no landing gear, dive brakes, or functioning flaps, the flaming Panther jet skidded down the runway for more than 3000 feet. Williams got out of the aircraft only moments before it was totally engulfed in flames.

“Everybody tries to make a hero out of me over the Korean thing,“ Williams once said. “I was no hero. There were maybe 75 pilots in our two squadrons and 99 percent of them did a better job than I did. But I liked flying. It was the second-best thing that ever happened to me. If I hadn’t had baseball to come back to, I might have gone on as a Marine pilot.”

There wouldn’t have been any complaints from the Marines if Ted Williams had decide to continue with his favorite team, least of all from his squadron leader.

“Much as I appreciate baseball, Ted to me will always be a Marine fighter pilot,” Glenn said. “He did a great job as a pilot. Ted was a gung-ho Marine.”