Russia’s questionable UCAV is dropping bombs now

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Earlier this week, Russian state-owned media announced that their Hunter UCAV had successfully dropped an unguided 1,100-pound bomb in its first publicized weapons trial. While this development is an entirely precedented step on the Hunter UCAV’s journey into operational service, it’s the things Russia left out of their press release that may suggest the sorry state of the program.

Claims versus reality

The story, which largely credits an anonymous source despite the outlet being Kremlin-owned, offered very little in the way of detail, but a whole lot in the way of claimed capability.

An unnamed Russian source claimed, “the newest sighting and navigation system installed on the Okhotnik makes it possible to use free-falling ammunition with an accuracy approaching that of a high-precision guided weapon.”

According to their source, the Hunter UCAV (called Okhotnik in Russian) successfully bombed a ground target at Russia’s Ashuluk range at some point in the past. The report does not offer details regarding the nature of the target, the exact type of munition, or even how the aircraft itself was controlled during the test flight.

Whether or not the Hunter UCAV did successfully complete such a munitions test is not worth much debate. It seems entirely likely at this point in the program’s development that the Russian military would be moving toward munitions testing. Other elements of the story, however, are difficult to reconcile with the facts as they’re presented. The Hunter UCAV successfully dropping a single bomb is a long way off from Russia’s claimed ability to strike stationary or moving targets autonomously.

In automotive parlance, that’s sort of like saying your car starts and runs, so it’s capable of winning the Indy 500.

The autonomous portion of the claim, in particular, is questionable, seeing as Russia has offered little in the way of explanation regarding how the platform is operated. We do, however, have other “autonomous” programs from the Russian Ministry of Defense to look to for context.

Russia’s troubled history with unmanned weapon systems

In 2018, Russia announced the deployment of their new infantry support tank drone dubbed the Uran-9. The announcement was met with much in the way of fanfare, that is until it was revealed by A.P. Anisimov, a Senior Research Officer from the 3rd Central Research Institute of the Russian Defence Ministry, that the platform had actually been an egregious failure during its time in Syria.

Here’s a portion of my coverage of the platform at the time:

“Despite claims of a three-kilometer range, operators lost control of their vehicles at distances ranging from only 300-500 meters when functioning around low-rise buildings. During testing, operators lost complete control over their Uran-9 assets for a short duration (up to one minute) seventeen times, with two more instances of loss of control lasting as long as one and a half hours.“

“The chassis of the platform itself proved to be riddled with issues, forcing in-field repairs of things like supporting and guiding rollers and suspension springs. The drive train also proved unreliable, its reconnaissance capabilities proved to be extremely exaggerated (it could identify targets no further than 2 kilometers away) and the mighty 30mm 2A72 automatic cannon failed to function properly on six different occasions. Anisimov went on to note that the targeting system for the gun relies on a visual feed provided by a camera that isn’t stabilized, making identifying, tracking and engaging targets extremely difficult at any distance.”–Russia was happy to report that their tank drone fought in Syria (forgot to mention it doesn’t work)

It actually makes good sense that Russia’s drone program would be lagging behind its national competitors. While the United States was already operating drones as far back as the year 2000, the Russian Ministry of Defense did not establish its own drone program until the fairly recent year of 2014.

Bombing on a budget

Russia’s stagnating economy and dwindling defense budget has forced the nation to prioritize high profile weapon systems like the Su-57 stealth fighter and the Status-6 nuclear torpedo, but has left the nation unable to fund it’s conventional modernization efforts. Even Russia’s sole aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, went from being a barely operational national embarrassment to little more than floating scrap in recent years, when Russia’s only dry dock capable of supporting a vessel of its size caught fire and sank with the carrier on it.

Thanks to overlapping international sanctions placed on Russia for its aggressive behavior in foreign territory, the decades-long effort to modernize Russia’s sizable military infrastructure has lagged behind its nation-level competitors in the United States and China. Russia has managed to keep its name in the papers thanks to token capabilities like the aforementioned fifth-generation Su-57–which exists only in the form of a dozen prototypes and a single serial production aircraft delivered one year after the first serial production Su-57 promptly crashed during its first flight.

A shared future with the Su-57

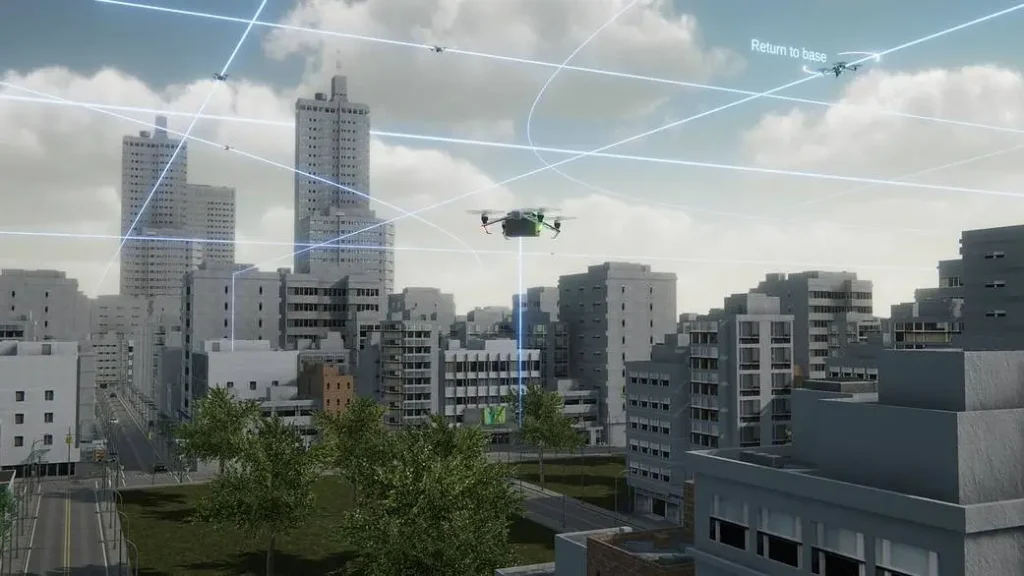

But Russia’s troubled stealth fighter now shares a future with its Hunter UCAV, with Russian officials announcing plans to network the two platforms in a similar way to America’s Skyborg or Australia’s Loyal Wingman programs. Each of these efforts aims to pair F-35 Joint Strike Fighters with AI-enabled UCAV wingmen that can support a wide variety of combat operations.

The Hunter UCAV was, in fact, originally billed as a stealth drone by Russian officials… but this latest announcement notably shies away from the stealth premise, saying instead that it leverages a “flying wing design and radar-absorbent coating” to reduce its radar signature. This softer sell on stealth is in keeping with our previous analysis of the platform, particularly when it comes to its engine–which appears to be a fourth-generation fighter’s engine without any shroud used to curb the drone’s radar or infrared signature. Stealthy it may be, but stealth is it not.

However, despite taking Russia’s claims with a grain (or a bucketload) of salt, neither the Hunter UCAV nor the Su-57 should be entirely counted out. While Russia doesn’t have the funding to devote as much R&D to their efforts as the United States, the nation does have a long and illustrious history of fielding highly capable air platforms. Russias Sukhoi Su-35, for instance, is widely seen as among the most capable fourth-generation platforms in service today.

So, should we believe what Russia has claimed about their Hunter UCAV? To some extent, sure. It very likely did successfully drop a bomb at some point. As for the rest, only time will tell.

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

F-35 ‘Lightning’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Military Affairs

How US Special Forces took on Wagner Group mercenaries in an intense 4-hour battle

F-16s carrying the A-10’s 30mm cannon actually saw combat

With NGAD uncertain, will America’s next air superiority fighter be the F-35?

Drone mystery solved? This little-known government program may explain New Jersey’s drone sightings

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page