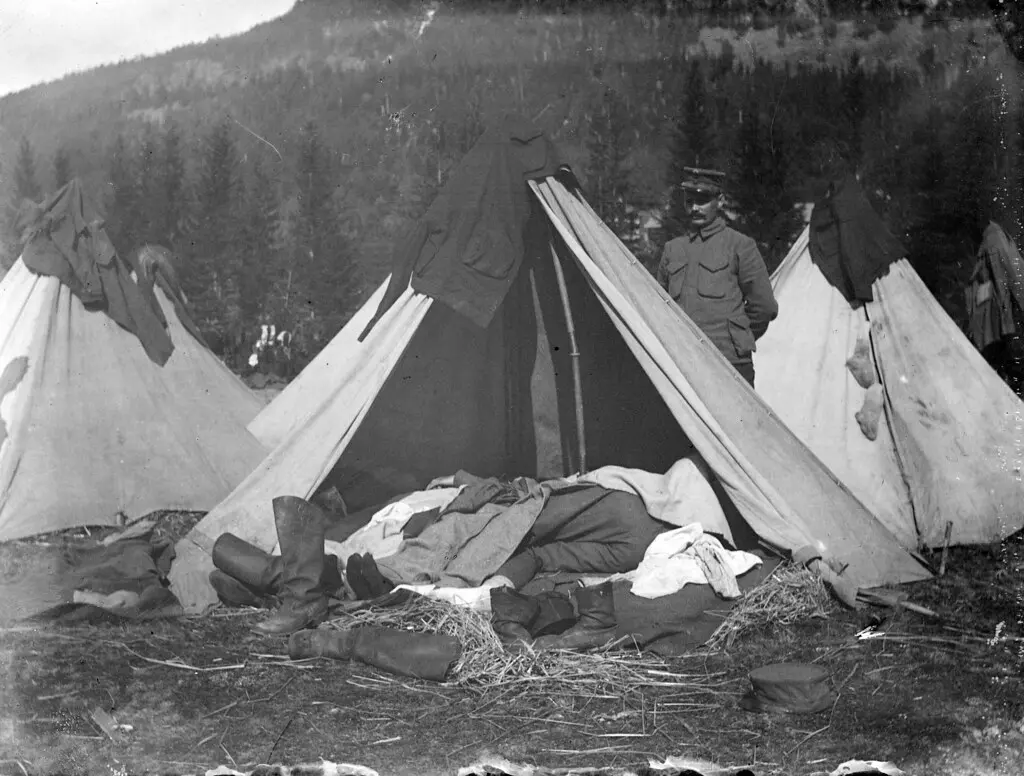

Navigating through the rain at an Army bivouac camp

- By George Hand

Share This Article

Bivouac (BW) is a military term that defines the ready state of troops positioned typically between the front lines (Forward Line of Troops — FLOT) and the secure comfort of the Forward Operations Base (FOB). For all the formality and ambiguity that the Army kneads into the bread of life, Bivouac is like being on a camping trip but with all the fun sucked out of it. Bivouac is a way to marshal troops and keep them at a combat-functional status.

When it comes to bivouacking, all involved typically hope not to be in BW status for more than just a few days or even just hours.

Every Soldier in the Army is issued a shelter half, that is, half of a pup-tent, so you have to team up with another Soldier to put together a full pup-tent that is still pretty small and barely accommodates two persons, but it certainly means well. They are non-pervious to the rain for the most part, but the user may find that flowing ground water and standing water pooled up is the greater enemy of the pup-tent.

As comfort goes, there is not much to be found at a Bivouac site. Wind and heavy rain can render a BW site into a kind of soup that adds to the struggle —and the struggle is real!

Once, during a particularly sudden and violent rain storm that struck our week-long BW stay in an infantry company’s rear area, I found myself incumbent to stay out of my pup-tent and weather the storm.

Just before the rain blast, I had fired up a decent dry Dominican Republic (DomRep) cigar of nearly seven inches in length. The storm whipped us for just about two to three minutes. As the insidious rain ceased to blast, I reached up to relight my DomRep, which must have surely been doused by then. After a couple of swipes, I failed to find the cigar, which certainly must have been washed away by the torrent.

“What’s that s**it all over your chin?” another Soldier asked me.

I had no idea of what he may be talking about standing there in all of his warm pup-tent dryness.

“Hold thy tongue, foul Sir… I fail to accept your erroneous expostulation of feces on my face.” I pulled out my survival mirror to have a gander at what the Soldier thought he saw and… fain would I fathom the nature specific, for there tenaciously clung my wayward cigar.

Related: The underwater firearms used by the world’s combat frogmen

The deluge had broken it off where my teeth once held it. It had then collapsed at its base and followed the contour of my chin and throat, much the same as a tactical aircraft hugs the terrain on a hard-to-follow Nap of Earth (NoE) trajectory.

With a snappiness of hand and finger, I recovered the second and last DomRep from my blouse’s front pocket and inserted it rudely into my pie hole.

“Any of you sons of mothers gotta light??” I asked.

The tent flared bright with the burning of a half-dozen or so lighters that framed eternal the shame that disgraced my miserable mug. I burned down the working end of the fresh cigar with a huff and puffed a puff that was sure to keep the eternal flame burning from my one and last DomRep cigar.

I was ready finally to head out of the glow of the tent to report to another location some 4,000 meters away to finish for the night or to receive yet another set of coordinates to report to. This training, you see, was day/night navigation with a map and compass. Not knowing if the navigation training would cease from one location to the next added intentional stress to those who participated in the training; working to and from Bivouac stations added yet another cruel layer of stress.

Related: Navy SEAL officer selection: Everything you need to know

I stepped out into that good night, yea though I did not go gently. At each BW station, several extra pup tents were constructed for Les Miserables who could not slice the mustard and declined (quit) to participate in the training any further. Quitting was a detestable thing, I did think. There would be none of it for the duration I could endure to participate in the training.

We, candidates, struggled at our BW site in our tiny tents to get ready to head out and navigate to our next required location. Just as we started, another deluge began its dump sequence on our camp.

Everyone dove back into their tents with the intent to wait out the rain leg and to move out later through dryer weather. I was worried that such a wait would burn up my time allowed to find my next compass point.

Related: The Long Range Desert Group and the birth of special operations around the world

I swam from my tent, into the woods, my last DomRep in danger of collapse and my doubt about correct navigation coordinates dwindling. When the rain did suddenly stop, I did an equipment check. The cigar had fallen by the wayside but my map was still dry and my flashlight still burned bright as the Star of Bethlehem.

I was still definitely in the fight.

I can boast that my decision to push through the rain from my last bivouac location was a good one. I finished the course defeating the accuracy and time standard; many other candidates were disqualified due to their choice to stay in bivouac and wait out the rain. I braved the storm and lost a cigar, but gained much-valued time.

By Almighty God with grace and honor,

geo sends

Feature Image: A fireteam of 910th Security Forces Squadron Defenders sets out to patrol a wooded area near their encampment, March 31, 2022, at Camp James A. Garfield Joint Military Training Center, Ohio. The 910th Civil Engineer Squadron joined the 910th Security Forces Squadron for a 24-hour field exercise in which the units established a bare base and provided perimeter defense. (U.S. Air Force photo/Eric M. White)

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Why Military Spouse Appreciation Day matters in our community

- This is why the Air Force is naming its highly modernized new bomber the B-52J

- Why is the Space Force’s new uniform camouflage?

- “Age of Empires 2: Definitive Edition” can teach valuable skills to service members

- The M4 carbine was never meant to be a primary infantry weapon

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

George Hand

Master Sergeant US Army (ret) from the 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta, The Delta Force. In service, he maintained a high level of proficiency in 6 foreign languages. Post military, George worked as a subcontracter for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) on the nuclear test site north of Las Vegas Nevada for 16 years. Currently, George works as an Intelligence Analyst and street operative in the fight against human trafficking. A master cabinet-grade woodworker and master photographer, George is a man of diverse interests and broad talents.

Related to: Breaking News, Special Operations

Congress demands answers on low testosterone issues among special operators

Video: US military sends aircraft to help with LA fires

Video: DARPA wants to arms a missile with cannons

How a Delta Force operator celebrated New Year’s in Bosnia

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page