- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

She may be an Army wife on base, but in literary circles, her husband is known as “Siobhan Fallon’s husband.” Her first book, You Know...

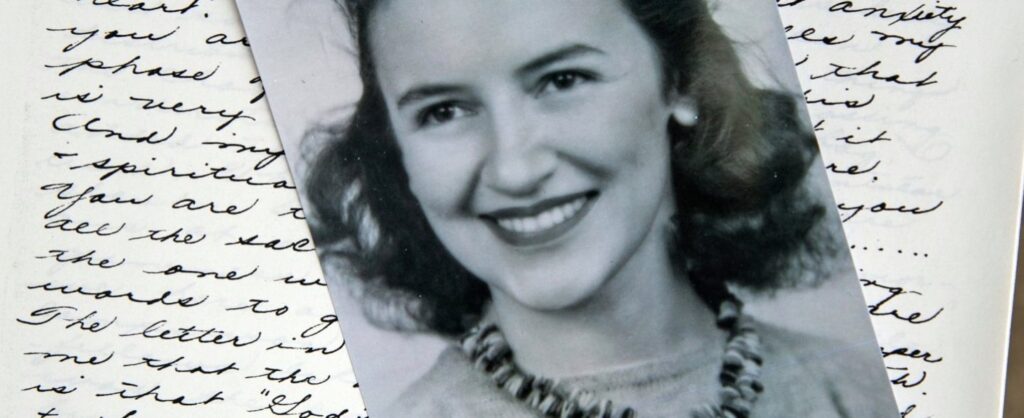

She may be an Army wife on base, but in literary circles, her husband is known as “Siobhan Fallon’s husband.” Her first book, You Know When the Men Are Gone, won the 2012 PEN Center USA Literary Award in Fiction, and the Indies Choice Honor Award, and the Texas Institute of Letters Award for First Fiction. Her second book, The Confusion of Languages, was called “a gripping, cleverly plotted novel with surprising bite” by National Book Award winner Phil Klay and a “clever” exploration of “friendships, parenting, and the civilian/military divide” by The Washington Post. She’s a stunning writer, but I’m also proud to call her a friend.

In this interview, Siobhan shares with me what it was like to be featured in Oprah Magazine, her advice for new military spouses, and what she’s working on next.

How did you and your husband meet, and how long have you been married?

My husband and I have been married for 16 years, if you count the quickie wedding on the beach a few weeks before his first deployment to Afghanistan in 2004– or 15 years, if you count the official church wedding we did with family and friends and a rocking Irish band, the Ruffians, when he returned.

We met in 2000, just after he had graduated from West Point, and I was working at my father’s Irish pub to pay for my Masters of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. My husband swore he wrote poetry, and he did pen me a few romantic snippets in those early days, which just goes to show how far an infantry man will go to woo a girl.

Your first book, You Know When the Men Are Gone, was featured in Oprah magazine – every writer’s dream. How did your husband and others on base respond to your success?

My husband has always been supportive of my career as a writer. The stories in You Know When the Men Are Gone take place at Fort Hood, Texas, where we had lived for three years. While we were there, my husband did two year-long combat deployments to Iraq. My fictional stories are about military families and were inspired by the life I was both living and witnessing at Fort Hood at that time. Of course, I was terribly anxious about what my husband’s chain of command would think of my work. So, we spoke with my husband’s commander, and I contacted all the public affairs officers and media people at Fort Hood, and every single person I asked told me I had a right to write whatever I liked. I was incredibly impressed… and relieved.

I also had my biggest book event at the Barnes & Noble in Killeen, Texas, right outside of Fort Hood. Standing room only (and trust me, I have had plenty of events that featured A LOT of empty chairs). I was touched by how many of the spouses in my old FRG (Family Readiness Group) came out to support me and my words. Everyone has been so very kind and good to me.

Where have you lived and what has been your favorite base so far?

My husband was stationed at Schofield Barracks when we were first married, and Hawaii is hard to beat. But it was far from home, and I missed my family terribly. And we also spent seven years overseas, between Jordan and Abu Dhabi.

If I had to choose a base stateside, I think I would go with Fort Benning, Georgia. I visited my husband there a few times when we were dating and he was attending the Infantry Officer Basic Course after West Point. Then he graduated from Ranger School shortly after 9/11, and I remember that reunion with such incredible joy and pride. A few years later, as newlyweds, we were there again for his Captain Career Course, which was fantastically social and full of exceptional officers and their spouses. That time in my life felt like the perfect introduction to the military world, and showed me the sort of teamwork I needed to embrace with both my husband and with my fellow spouses. I also managed to reach my lifetime highest quota of cat care when we lived there—we had SIX cats (something my husband never lets me forget). My father had also gone to Airborne School at Fort Benning when he was a soldier in the 1960s. The nostalgia of being in such a historic place at pivotal moments in my married life gives it a warm glow in hindsight.

Your second book, The Confusion of Languages, takes place in Jordan during the Arab Spring. What surprised you most about living in the Middle East?

There is a seemingly small detail of life in the Middle East and Gulf that comes back to me now in this time of Covid, especially with our new mask wearing. Our face coverings remind me of the niqabs or veils the women would often wear in Jordan and Abu Dhabi, or anywhere that is predominantly Muslim. I can’t tell you how many times I would walk by a woman covered in black from head to toe, just her eyes showing, and there I was, this woman with her messy blond hair and probably showing too much arm and leg, breaking goodness knows what rules. But I would smile, and I would get the most amazing, generous smile in return. Even if I couldn’t see her mouth, I could see it in her eyes, the up-turn at the corners, the realization that we were connecting even if it was just for a second.

On the surface, to have that physical barrier between your face and someone else’s gives you a certain anonymity, and the distance can be off-putting, or at least allow you to hide. But from standing over barrels of fresh spices in a souk in Amman, to the kid’s section in a Target in Fairfax, Virginia, we have the ability to look in each other’s eyes. We can try to make our smile known. I think we mustn’t forget that. We have to look, acknowledge, say hello, and smile, even if our mouths are invisible. We have to continue to make whatever contact we can; we have to remember that underneath our differences and fear of the unknown, we are still the same.

What book is on your nightstand right now?

Brave Hearts: Indian Women of the Plains, by Joseph Agonito. It’s a nonfiction book that gives the biographies of twenty-two Native American women; how they managed the shifting landscape of the late 1800s, when the old ways of the Plains were being subsumed by reservation life and assimilation into Anglo American society. They are woman warriors, medicine women, concert violinists, teachers, nuns. It’s an enlightening read, and plays into my current work.

What is the most challenging part of being a military spouse? Do you have any advice for new military spouses?

The hardest part for me is the uncertainty. I know everyone faces upheaval and change. But I have lost count of how many times we thought my husband had a particular position secured, and suddenly our future would abruptly change, and he received very different orders and a new destination and time zone for us all. And it never gets easier—the packing and unpacking, the new schools for the kids, new work for the spouse, finding new doctors and grocery stores and friends.

But the bright side is that we have seen and experienced things we never would have without being part of the military community. My daughters have climbed pyramids in Egypt, ridden camels in the Gulf, been to the Garden of Gethsemane in Jerusalem, seen the Eiffel Tower, been awed by German castles, visited Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka, not to mention crisscrossed up and down our own gorgeous United States. They have made friends with kids from all over the world. We wouldn’t have had those opportunities without the Army.

Another thing I am grateful for, especially during this pandemic, as I see family members and friends out of work and struggling, is that the military life continues to offer job security, health insurance and benefits. We are so very thankful.

Describe your dream place to write.

Honestly, my own office: My books on the shelves and stacked up on the floor. A window to a blue sky and green trees. Silence and stillness in which to think and write (though, with two little girls underfoot, that part is nearly impossible to attain these days). But I have been fortunate enough to create a space that has everything I need for the novel I am currently working on.

What are you working on now?

I’m writing a novel about the fallout of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where the Seventh Cavalry, under General George Armstrong Custer, was soundly defeated by the combined force of the Sioux and Cheyenne.

There is a little remembered court of inquiry that took place in 1879, two years after the battle. It examined the behavior of Custer’s second in command, Major Marcus Reno, and tried to determine if he had been a coward. During the battle, Reno retreated from his portion of the fight with his men, and took what many see as an inordinate amount of time to regroup with fresh troops and go to Custer’s aid, and when he did attempt to find Custer, he didn’t get far before retreating again. The only American soldier survivors of that battle are the ones who were with Reno, so he could be seen as a savior of sorts. On the other hand, it is often argued that if Reno had gotten through to Custer, he could have changed the entire outcome of the battle.

My novel uses this court of inquiry to show how many lives were affected by the Battle of the Little Bighorn, from the American military families suddenly bereft without their husbands and fathers, to the American soldiers and the Native Americans who fought them. Though the Cheyenne and Sioux were victorious that bloody day, by the end of that summer they had either been herded onto reservations or fled to Canada.

I also focus on the role of Custer’s wife, Libbie: how she helped orchestrate the Reno Court of Inquiry and bring her influence against Major Reno. Libbie wrote three very popular books about life with her husband, and toured widely, lecturing in an effort to defend her husband’s reputation. I find her to be the quintessential military spouse. She lived a hard life on the frontier that puts most of our current military moves and deprivations to shame, but she always stood by her man. Then, after his death, she never remarried, spent 57 years defending him, traveling the world, visiting writing colonies in upstate New York, securing benefits for war widows, supporting the arts as well as creating education initiatives for military children. She fills me with awe. I hope my novel does her story justice.

Find Siobhan Fallon on her website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Victoria Kelly is a former military spouse and the author of When the Men Go Off to War and Mrs. Houdini. She graduated from Harvard University and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Find her at victoria-kelly.com.