- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

My introduction to Jehanne Dubrow’s work was her 2010 book, “Stateside,” which I read in my first year of marriage as a Navy wife. I...

My introduction to Jehanne Dubrow’s work was her 2010 book, “Stateside,” which I read in my first year of marriage as a Navy wife. I was writing the first poems I had attempted since my freshman year of college, and I marveled at how expertly (and seemingly effortlessly) she wrote (of course, now I realize that the mark of a great writer is making a phrase seem like you wrote it in 30 seconds when it actually took three hours).

In many ways, Jehanne launched the era of the military spouse poet. Today, she is the author of an incredible nine books of poetry, as well as a book of creative nonfiction, “Throughsmoke: An Essay in Notes” (New Rivers Press, 2019). Her husband, Jeremy, recently retired from a 20-year career in the U.S. Navy, and they live in Texas, where Jehanne is a professor of creative writing at the University of North Texas.

Jehanne’s work has been featured by “American Life in Poetry,” “The New York Times Magazine,” “The Slowdown,” “Fresh Air,” “The Academy of American Poets,” and more. She is the founding editor of the national literary journal, “Cherry Tree.”

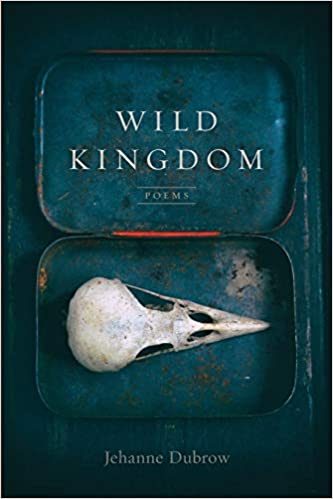

Her most recent book, “Wild Kingdom,” was published this year by LSU Press. I’m so excited to share my interview with her, where we discuss her book, her military-to-civilian transition, her writing advice, and what she’s working on next. I am also fortunate to now call her a (remote, as we now all are) friend.

RELATED: INSPIRING BOOKS FOR ARMY MOMS

You can find Jehanne and read sample poems on her website. You can buy her books on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and more.

Congratulations on the publication of your recent collection, Wild Kingdom! You’re a professor of creative writing at the University of North Texas, and your new book explores the theme of academia. It seems to me like the college town and the military town can have some strong parallels. Have you seen any similarities?

Oh, this is such a good point. I do think these two kinds of communities have some traits in common. For instance, both have their own distinctive languages, customs, etiquette, which a newcomer would be wise to learn! I also think both communities have the potential to be welcoming spaces that offer friendship, support, and intellectual growth; but, when people use their power and influence badly, these communities can become sites of cruelty too.

Your husband recently retired from a 20-year career in the U.S. Navy. What was the biggest thing you were looking forward to? What is the biggest thing you miss?

For most of the first 14 years of our marriage, my husband and I lived apart. An academic career is not portable, and so I was anchored to my home institution. Even when my husband was back here in the U.S., we mostly maintained two separate households in two different states. With his retirement, I was really excited for us to finally live together. And it has made for a whole new marriage: to share meals, to run ordinary errands, even to occasionally grow tired of one another’s company! What do I miss? I was always fascinated by my husband’s work in the Navy, hearing the stories he told about the intricate interpersonal dynamics of a ship, laughing about the silly things people do to avoid boredom during a deployment. My husband’s service offered me insights into a world that’s utterly different from my own bookish life in a classroom with undergraduate and graduate students, where we spend hours debating the meaning of a line of poetry or the consequences of a comma versus a semicolon.

Your book-in-progress, “Civilians,” will be the final book in your military trilogy that includes “Stateside” (Northwestern UP, 2010) and “Dots & Dashes” (Southern Illinois UP, 2017). What topics have you been exploring for this book?

With “Civilians,” I think about how much of military life stays with a service member (and the rest of the family) once that service ends. The word “civilian” is defined by absence and negation. A civilian is a person who is not: not a member of the military, not uniformed. Now, my husband and I are simply two civilians; he’s no longer an officer, and I’m no longer a dependent. How does this change of labels alter our identities, both as individuals and as a couple?

A few of my favorite lines from your new book are: “Sometimes we met with our questions / in the small furrows of a page,” and “and somewhere beneath the cold / I had to believe little cups of gold / the sharp green stems of crocuses / were poking through.” When a really good line comes to you, is it an “aha moment” or do you rework it over and over again?

It really depends! When I’m writing–both poetry and prose–I always begin with the sound and taste of language. I work from the music of the writing toward meaning. Sometimes a good line or phrase just arrives. And sometimes I have to work until I discover where the image or metaphor wants to go. I revise most of my poems 50-100 times, always reading each draft out loud to make sure that the writing is “delicious” to speak. By the time the writing reaches a polished state, I hope it will feel natural and effortless, even if I’ve struggled with every word.

I teach creative writing to veterans through the Armed Services Arts Partnership, and I am always overwhelmed by the wonderful stories they share through their writing (and how hesitantly they begin to write, not thinking of themselves as “writers”). What is the biggest piece of advice you have for servicemembers, veterans and spouses who want to process their experiences through poetry?

I think my advice is the same as I would offer to any aspiring poet: read. Read a lot. Read contemporary poets, and poets who have been dead centuries. At the beginning, just focus on learning about different elements of craft: how to use the five senses to create vivid images, how to handle figurative devices like metaphor, how to make your language sing on the page. Eventually, as the voice of your poems becomes more experienced and authoritative, you can start to explore the particular demands of your subject matter, the stories you want to tell.

What are you reading right now?

I’m writing a nonfiction book about our sense of taste, tentatively titled “Taste: A Book of Small Bites.” As part of my research, I’ve been reading lots of food memoirs, cookbooks, and historical books about topics like mushrooms, chocolate, and sugar. I’m also currently reading “The Poems of Emily Dickinson,” because I’m writing a book about the experience of reading her poems every day for a year. Let me tell you: Dickinson, who was famously reclusive, has a lot to teach us all about solitude and our relationship with society, especially during this pandemic era.

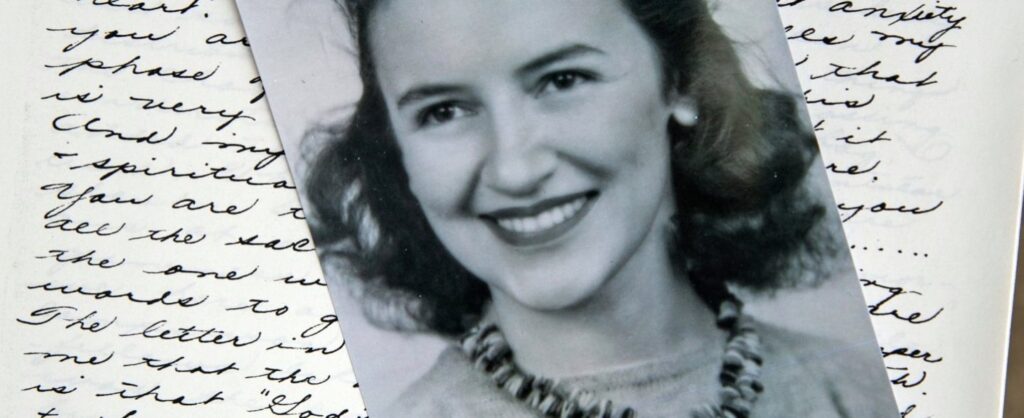

Feature image: Courtesy of JehanneDubrow.com