Here’s why Elon Musk is wrong about fighter jets (but right about drones)

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Last week, Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk ruffled some feathers during a discussion with Air Force Lt. Gen. John Thompson at the Air Force Association’s Air Warfare Symposium. The controversial tech mogul, who is no stranger to drawing headlines and occasionally criticism, voiced concerns over America’s apparent love affair with Lockheed Martin’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, first calling for competition for the advanced fighter, and then going further to say that the era of manned fighter jets was over.

“Locally autonomous drone warfare is where it’s at, where the future will be,” Musk said. “It’s not that I want the future to be this, that’s just what the future will be. The fighter jet era has passed. Yeah, the fighter jet era has passed. It’s drones.”

Musk went on to say that even the F-35 wouldn’t stand a chance against a sufficiently advanced drone that coupled computer-augmented flying with human control.

When the story broke, we here at Sandboxx pointed out that Musk is right that a technologically advanced drone could potentially do a lot of things a manned aircraft couldn’t — including manage hypersonic maneuvers that would leave most human pilots unconscious as a result of the G-forces. Scramjet technology has proven effective at propelling unmanned aircraft to hypersonic speeds in the past, and it seems entirely feasible that this tech will find its way into UCAVs (Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles) in the future.

But, we noted, the problem with Musk’s bright idea is that information traveling at the speed of light is actually too slow for the sort of control drone operators would need for such a platform. Even with a somewhat local operator, as Musk pointed toward, the time it would take to relay sensor data from the drone to the operator, followed by the operator processing the information and making a decision, followed by those commands being transmitted back to the drone is simply too slow a process for the split-second decisions that can be essential in a dog fight.

In other words, Musk’s plan is hypothetically right, but likely won’t work in practice for some time to come.

“For a long time, we’re still going to need the manned aircraft on the fighter and bomber side,” Air Combat Command chief Gen. Mike Holmes, an F-15 Eagle pilot, said Wednesday during the annual McAleese Defense Programs Conference. “We will increasingly be experimenting with other options, [and] we’re going to work together.”

The future of air combat likely will include some combination of manned and unmanned aircraft, which is exactly the future the Air Force’s Skyborg program is aiming for. Using “loyal wingman” armed drones like the Kratos Valkyrie, the Air Force hopes to couple fighters like the F-35 with support drones that can extend sensor range, engage targets, and even sacrifice themselves to protect the manned aircraft. In theory, one F-35 could control a number of drones that bear the majority of the risk, flying ahead of the manned jet.

“We can take risk with some systems to keep others safer,” the Air Force’s service acquisition executive, Dr. Will Roper said. “We can separate the sensor and the shooter. Right now they’re collocated on a single platform with a person in it. In the future, we can separate them out, put sensors ahead of shooters, put our manned systems behind the unmanned. There’s a whole playbook.”

The combination of the sort of technology in play in Skyborg and rapidly developing hypersonic propulsion could put the power of hypersonic platforms in the hands of fighter pilots, just likely not in the jets they’re flying.

Of course, doing so would greatly increase the mental load on pilots in the fight, particularly if their means of controlling their wingmen drones is too complex. One of the selling points of the F-35 that doesn’t get much play in the press is its ability to fuse data from disparate sensors into an overlapping augmented reality display. Prior to this advancement, pilots had to read and manage multiple displays and gauges, combining the data in their minds to make decisions. In the F-35, friendly and enemy assets are clearly identified with colored indicators, as are air speed, altitude, and other essential information. At night, pilots can even use external cameras with their augmented reality helmets to look through the aircraft at the ground below.

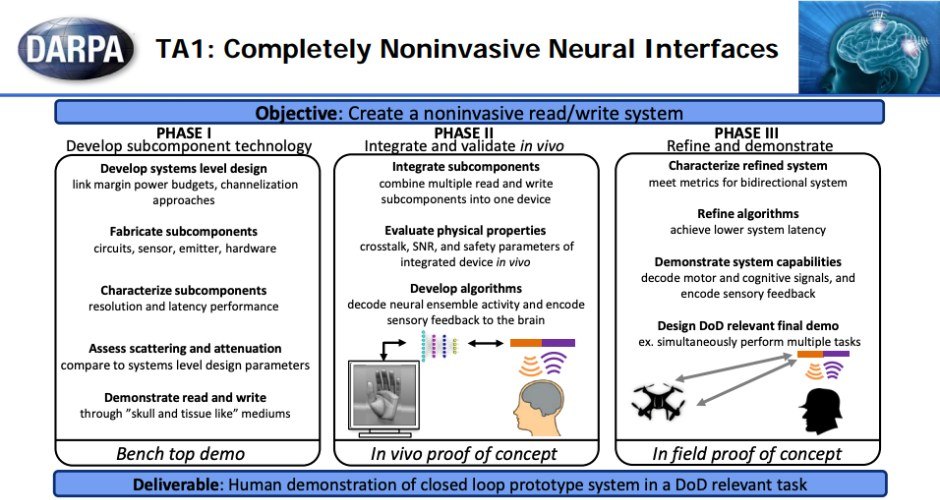

A complex drone-control interface could be a step backward in a pilot’s ability to manage the flow of data, but a DARPA experiment first revealed in 2018 might just be able to solve that problem.

At the time, Justin Sanchez, director of DARPA’s Biological Technologies Office, explained that two years prior, DARPA had successfully utilized what he called a “Brain Computer Interface” to put one volunteer in control of not one, but three simulated aircraft at the same time. The “N3 System,” as they call it, could give pilots the ability to manage their drone wingmen using only their mind.

“As of today, signals from the brain can be used to command and control not just one aircraft but three simultaneous types of aircraft,” he said at the “Trajectory of Neurotechnology” session at DARPA’s 60thanniversary event

In later experiments, volunteers even experienced feedback from the aircraft, transmitted into their brains to feel like a tingling sensation in the hands when the aircraft was pushing back against steering in a certain direction. The only problem is, currently, this system only works for volunteers who have had surgically implanted electrodes in their brain. The volunteers were all people with varying levels of paralysis, as this same technology could feasibly be used to control exoskeletons that could help a patient regain the ability to walk.

“The envisioned N3 system would be a tool that the user could wield for the duration of a task or mission, then put aside,” said Al Emondi, head of N3, according to a company spokesperson. ” I don’t like comparisons to a joystick or keyboard because they don’t reflect the full potential of N3 technology, but they’re useful for conveying the basic notion of an interface with computers.”

So, while it’s true that a drone isn’t subject to same physical limitations a manned aircraft is, the tradeoff is that a drone would need to have an extremely advanced, fully autonomous flight system in order to execute maneuvers at the fuzzy edge of its capabilities, because communications lag would make such performance impossible in a human-controlled drone at a distance. If the drone weren’t under the control of a nearby pilot, the only choice would be to give the drone itself decision-making capabilities, either through an on-board processor, or through an encrypted cloud computing process.

To date, that level of tech simply doesn’t exist, and even if it did, it would pose significant moral and ethical questions about what level of warfighting we’re comfortable relinquishing to a computer. Friendly fire incidents or unintentional civilian casualties are complicated enough without having to defend the actions of a Terminator drone, even if they were justified.

In the future, it seems entirely likely that drones will indeed be more capable than manned fighters, but they still won’t be able to fly without their cockpit-carrying counterparts. A single F-35 pilot, for instance, may head into battle with a bevy of hyper-capable drone wingmen, but the decision to deploy ordnance, to actually take lives, will remain with the pilot, rather than the drone, just as those decisions are currently made by human drone operators.

Elon Musk is right that drones can do incredible things, but he’s wrong about the need for human hands on the stick. The future doesn’t look like Skynet, but it may look like the terrible 2005 movie, “Stealth.”

Elon Musk may be good at building rockets, electric cars, and even tunnel boring machines, but when it comes to predicting the future of warfare, he’s just as fallible as the rest of us.

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Kinetic Diplomacy’ Bumper Sticker (White)

$8.00 Add to cart

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower, Military Affairs

What do we know about China’s new ‘6th gen’ fighters?

Former Navy SEAL and pioneer combat medicine physician is awarded Presidential Citizen’s Medal

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page