Why Russia’s Mach 3.2 MiG-25 couldn’t catch the Blackbird

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

Despite flying into the sunset nearly a quarter-century ago, Lockheed’s legendary SR-71 Blackbird was so far ahead of its time that even today, some 59 years since its first flight, there has yet to be a single aircraft to challenge its position atop the podium of fastest crewed jets in history. Throughout its three decades of service, the Blackbird famously had over 4,000 missiles of all sorts fired at it, and managed to outrun every single one.

But no aircraft is invincible and the Blackbird was no exception. With Soviet interceptors like the MiG-25 achieving speeds as high as Mach 3.2 in 1971, and Soviet surface-to-air missiles like the SA-2 known to exceed Mach 3.5, the SR-71’s stated top speed of Mach 3.2 wasn’t necessarily that much faster than its competition… but the SR-71’s ability to evade intercept was really about much more than top speed alone.

The SR-71 was borderline science fiction come to life in the 1960s

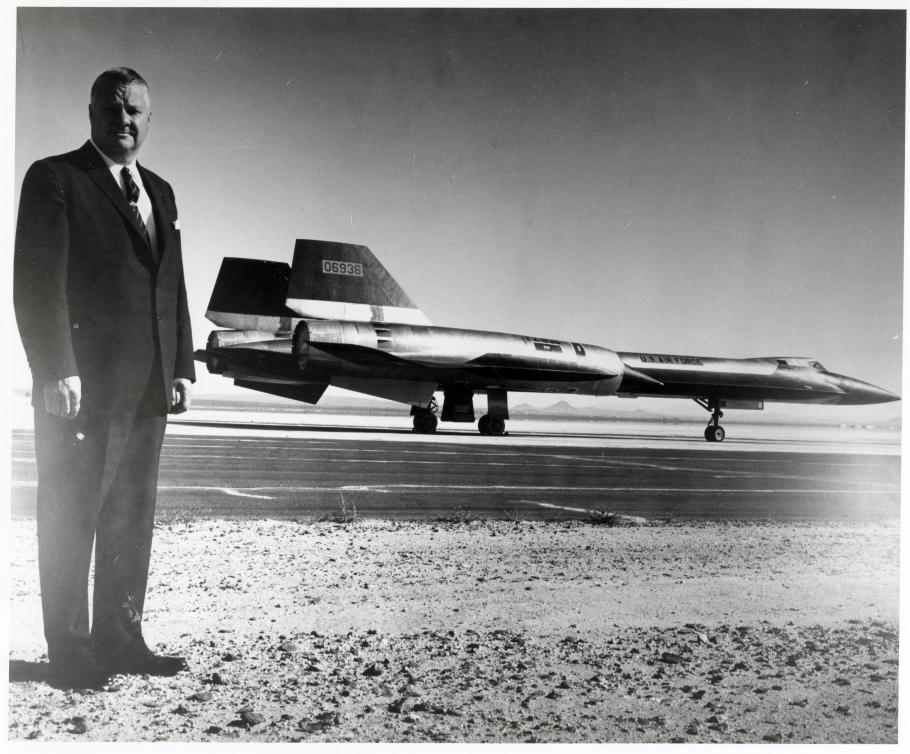

Designed by famed aeronautical engineer Kelly Johnson, the SR-71 was designed to defeat the most capable air defense systems and intercept fighters the planet had ever seen through a combination of early stealth, meticulous mission planning, and perhaps most important of all, sheer power.

The SR-71 can be seen as perhaps the most successful design of Kelly Johnson. Johnson had already proven his designing mettle with previous projects like World War II’s P-38 Lightning, America’s first jet fighter, the P-80 Shooting Star, and most notably to that point, the high-flying U-2 spy plane. In fact, it was Johnson’s efforts during the U-2 program that led to the establishment of the secretive military facility many of us know today as Area 51. But as ground-breaking as his previous efforts were, the Archangel program and the SR-71 it produced were in a league of their own.

While the SR-71’s disclosed top speed of Mach 3.2 tends to get the lion’s share of attention, it wasn’t just that speed that made the Habu such an incredible platform. After all, aircraft like the rocket-powered North American X-15 went significantly faster (Mach 6.7) later that same decade. But while the X-15 could cover maybe 240 miles per flight and needed a complete engine rebuild after every hour of operation, the SR-71 was designed to fly faster than a speeding bullet for hours and hours on end before landing safely on an airstrip to be refueled for another flight the following day.

“The idea of attaining and staying at Mach 3.2 over long flights was the toughest job the Skunk Works ever had and the most difficult of my career,” Johnson later recalled in his autobiography. “Early in the development stage, I promised $50 to anyone who could find anything easy to do. I might as well have offered $1,000 because I still have the money.”

The Blackbird’s ability to sustain Mach 3+ speeds for so long created tons of engineering hurdles like the need to invent new kinds of wire for the avionics systems that could survive massive temperature fluctuations. The engineers also needed to specially formulate new hydraulic fluids that would still work at ground level and 16 miles above the earth. In order to meet both weight and temperature requirements, the decision was made to use titanium for 93% of the aircraft’s structure… but the only place to get enough of it for production was from the Soviet Union. So, the CIA established a series of shell companies to secretly procure the titanium from the Soviets that would be used to spy on the Soviets.

Even the windshield posed unique problems, as the extreme temperatures of sustained Mach 3 flight would make glass translucent instead of transparent, obscuring the pilot’s view. Instead, the SR-71’s windows had to be made out of solid 1.25-inch-thick pieces of quartz that were sonically fused to the airframe. Even then, the Quartz windows would get so hot during flights that crews would hold their rations a few inches from them to rapidly heat up their in-flight meals.

Related: A realistic analysis of what F-16s can really do for Ukraine

The SR-71’s combination of speed and stealth made it an extremely tough target

The SR-71’s relatively small radar cross-section and extreme speed made it an exceptionally difficult target for ground-based air defense systems. According to reports, the 107-foot-long Blackbird carried a radar cross-section of just 22 square inches (0.1 meters squared), which meant air defenses wouldn’t see it coming until the last minute. At that point, even attempting to launch an SA-2 missile, which with a top speed of Mach 3.5 was faster than the Habu, was effectively a lost cause. By the time the missile would be airborne, the SR-71 would simply already be out of range.

But by 1970, the Blackbird had new competition atop aviation’s high-speed leaderboard and in the skies over Soviet-controlled territory: the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25.

The MiG-25 was developed largely in secret by the Soviet Union as a response to the nuclear-capable supersonic bombers the United States was developing at the time. Word of this new high-speed interceptor, then known as the Ye-155, reached the United States as early as 1964, but it really caught their attention in 1965, when the program broke cover thanks to the Soviet Union announcing the jet broke the world speed record at 1,441 miles per hour. But it wasn’t until 1967 that Uncle Sam would get its first clear look at the new Soviet superfighter, thanks to an American delegation snapping photos of them flying by during an exhibition near Moscow.

With massive air intakes, vast wings, and twin-engine outlets big enough to picnic in, the American defense apparatus was immediately concerned with what they saw. And it would only get worse from there. In 1971, the Soviet’s secretive MiG-25s were regularly clocked at speeds between Mach 2.5 and 2.83 by Israeli forces during reconnaissance flights over the Sinai Peninsula – faster than any other fighter on the planet could muster. And if that didn’t raise the eyebrows of Defense officials enough, one MiG reportedly exceeded Mach 3.2 while flying higher than 80,000 feet when Israeli F-4s attempted to intercept it.

Related: When Russian attack helicopters opened fire on the press

The SR-71 and MiG-25 flew at Mach 3.2 in very different ways

On paper, then, the MiG-25 seemed to be a match for America’s high-flying SR-71 Blackbird… but that’s the problem with comparing things like top speed without greater context.

You see, the Soviet MiG-25 could achieve speeds as high as Mach 3.2 during very brief all-out sprints that would cause irreparable damage to its powerful (but finicky) Tumansky R-15 turbojet engines. The SR-71, on the other hand, would sustain those speeds for hours on end without breaking a sweat, thanks to its unique Pratt & Whitney J58 turbojet engines that included bypass tubes that funneled cold air directly into the afterburners (leading to the J58 sometimes being called a “turboramjet”) and the engine’s first-of-their-kind directionally solidified turbine blades that could withstand higher temperatures than any jet engine previously could.

In other words, the MiG-25 might be able to occasionally exceed Mach 3 at great cost, but the SR-71 practically lived there. As a result, by the time Soviet pilots got word that there was a Blackbird headed their way, they had little chance of getting their aircraft airborne and on its tail before it was simply gone.

As Soviet MiG-25 pilot Lt. Viktor Belenko explained after defecting to the West in 1976, the Foxbat, as the MiG-25 was known, simply couldn’t climb fast enough to close with an SR-71 screaming past at sustained speeds above Mach 3, and even if it could, their air-to-air missiles lacked the thrust required to close the distance between them. Even when flying at an SR-71 head-on, Belenko explained, the Habu’s closure rate was too much for the Foxbat’s guidance system to manage.

“They taunted and toyed with the MiG-25s sent up to intercept them, scooting up to altitudes the Soviet planes could not reach, and circling leisurely above them or dashing off at speeds the Russians could not match,” Belenko explained.

Related: The Soviet version of Operation Paperclip was way bigger but less successful

One Soviet MiG-31 pilot did claim to get a lock on the SR-71, but…

Years later, former Soviet pilot Captain Mikhail Myagkiy would claim to have successfully locked onto an SR-71 in his MiG-31, but opted not to shoot because the aircraft had not violated Soviet airspace. This account has not been confirmed by the American side, however, and it’s worth noting that Soviet pilots weren’t exactly known for being reserved in their judgment to fire.

For example, in 1983, an incident involving a Korean Air Lines Boeing 747 resulted in an intercept from Su-15s. The Su-15s fired a few warning shots with their cannons, and although the pilots could clearly see that it was a civilian airliner, they opted not to report that information back to their command element. In fact, according to reports, the fighters didn’t even try to contact the airliner by radio.

“I saw two rows of windows and knew that this was a Boeing. I knew this was a civilian plane. But for me, this meant nothing. It is easy to turn a civilian type of plane into one for military use,” Soviet pilot Col. Gennadi Osipovitch later told the New York Times. “I did not tell the ground that it was a Boeing-type plane; they did not ask me.”

Osipovitch then took position behind the wayward 747 and fired two K-8 infrared-guided air-to-air missiles, destroying the aircraft and killing all 269 passengers onboard. Seeing as Soviet leadership at the time blamed the shootdown on provocations masterminded by the United States, it seems unlikely that another Soviet fighter pilot with a solid lock on an SR-71 just outside of Soviet airspace would suddenly develop a thorough understanding of international law.

Related: The Soviets crashed into the moon while Apollo 11 was on it

The only foreign fighter ever to lock onto the SR-71 was Swedish

As the years wore on, only one foreign fighter ever managed to actually secure a lock on Lockheed’s SR-71 – a specially trained group of Swedish Air Force JA-37 Viggen pilots, who deserve a great deal of credit for their exceptional operational planning and technical skill that allowed the comparatively slower and lower-flying Viggens to earn this distinction.

However, one could argue that these intercepts were only possible because the U.S. Air Force did not perceive Sweden as a threat, and as such, did little mission planning to prevent them. In other words, one could argue that Sweden’s Viggens successfully managed to intercept Blackbirds that weren’t necessarily actually trying to evade them. In fact, in one incident that remained classified until just a few years ago, Viggens sent to intercept an SR-71 quickly transitioned to escorting it when they realized one of its engines had exploded. As the Blackbird quickly lost both speed and altitude, two sets of Viggens rotated in and out to protect it from Soviet interceptors until it could reach friendly airspace.

Those Viggen pilots were eventually awarded U.S. Air Force Air Medals for their impromptu defense of the American jet, which serves as a valuable reminder that even the competitive spirit that motivates so many in the military aviation community can’t overcome the professionalism and mutual respect shared among the world’s top aviators.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Another one bites the dust: Ukrainian long-range strikes take out another Russian warship

- These are 3 popular misconceptions about the Navy SEALs

- You’re probably thinking of missile costs all wrong

- China presents an ‘urgent challenge’ Pentagon’s new weapons of mass destruction strategy says

- SOCOM’s potential new firearm is a revolution

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Airpower

Where do NATO reporting names come from?

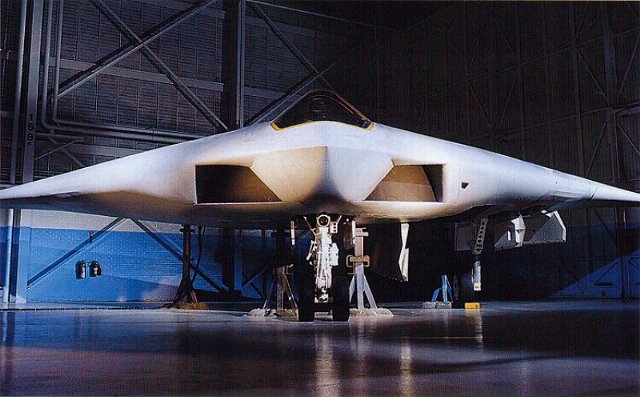

The A-12 Avenger II would’ve been America’s first real ‘stealth fighter’

Why media coverage of the F-35 repeatedly misses the mark

It took more than stealth to make the F-117 Nighthawk a combat legend

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page