USAF’s oldest living general, Harry Goldsworthy, turns 107

- By Military.com

Share This Article

Read the original article on Military.com. Follow Military.com on Twitter.

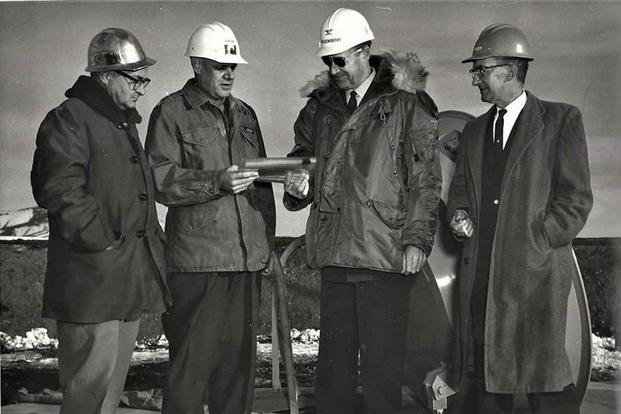

In 1960, then-Col. Harry Goldsworthy and his team were given the near-impossible task of getting an intercontinental ballistic missile site up and running in roughly two years’ time. There was little confidence they would succeed.

The Air Force Ballistic Missile Committee, reporting to the Office of the Secretary of Defense, had just approved Malmstrom Air Force Base, Montana, to host the first Minuteman I nuclear missile silo and launch site.

Political pressure was mounting. Silo, launch control and support facility projects across the U.S. to host Minuteman, Atlas and Titan ICBMs were six months behind schedule, even as the Soviet Union had already flown the world’s first ICBM powerful enough to launch a nuclear warhead.

So Gen. Curtis LeMay, the Air Force vice chief of staff at the time, tasked Goldsworthy, who had been chosen to oversee Malmstrom, and 17 other men to get the ICBM site project back on track. They formed what was known as a site activation task force, or SATAF, under the Ballistic Missiles Center of Air Materiel Command, today known as the Space and Missile Systems Center at Los Angeles Air Force Base, California.

“It hadn’t been done before, and we were building the silos before they even fired a missile [from the] silo test program,” Goldsworthy said Thursday in a phone interview with Military.com. “The whole program was a little overwhelming, but it was one that gave me a great satisfaction of getting it done.”

The first operational silo was completed at Malmstrom in 1961; construction of all 150 sites at the base was completed in 1963. It’s one of the many milestones Goldsworthy noted from his 33-year career in the service. This month, he is celebrating a new landmark: On Saturday, Goldsworthy turns 107 years old. He is believed to be the oldest living retired Air Force general in the world.

“It was a wonderful career, and I’ve had a great life,” said Goldsworthy, who retired in 1973 as a lieutenant general. “I’m just looking forward to surviving, I guess.”

Pilot Service in World War II

Goldsworthy wanted his life to be about service. The Spokane, Washington, native was convinced by a college buddy to join up in 1936, taking a reserve commission as an infantryman in the Army. He served at Fort George Wright, near his home.

The Army Air Corps accepted him for flight training in 1939. A year later, he earned his wings at flight school at Kelly Field in Texas. Eventually, Goldsworthy would be hunting German U-boats in the Caribbean from a B-18 heavy bomber retrofitted with radars to detect submarines. He patrolled near Puerto Rico and Trinidad until 1943.

The mission was to prevent U-boats from surfacing and using their periscopes to search for nearby targets. Goldsworthy, who put in more than 2,000 flight hours on that mission, said he saw “maybe one” submarine surface. He recalled dropping anti-submarine depth charges, but not a single one hit. “That was that submarine’s lucky day,” he said.

Goldsworthy was reassigned to a B-25 Mitchell bomber replacement training unit in South Carolina, then headed off to the South Pacific in 1945. Stationed in the Philippines, he flew seven combat missions and a number of patrol flights against Japanese forces in Balikpapan on the Southeast Asian island of Borneo in support of Australian landings on the island.

“We got there very late,” he said of the campaign.

During his last flight in July 1945 to support the U.S. Army over the Philippine island of Luzon, his B-25 sustained damage from ground fire. He and his crew had to bail out, landing in the jungle. He still has some of his parachute gear from that day.

“We all felt a little uneasy on that one,” he said. The crew was scattered across the island, but after a couple hours, he was picked up by Philippine scouts supporting the Army.

“I was going down the trail trying to to work my way north, and there was a little man with a big gun. And he put his gun down and he pulled out an ID and had the same kind of ID that I did, so I knew he was working for the Army. And then we went for a long walk through the jungle,” Goldsworthy said.

Days later, the United States detonated two atomic weapons over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading to Japan’s surrender.

Following an occupational duty at Itami Air Base in Japan, Goldsworthy returned stateside, where he was assigned to fly the B-29 Superfortress followed by the B-36 Peacemaker. He became the commander of the 11th Bombardment Group at Carswell Air Force Base, Texas, in 1948 — a year after the formation of the U.S. Air Force as a separate service.

The Century Series Supervisor

Goldsworthy, who said he never saw himself in a role at the Pentagon, was called up to Washington, D.C., in July 1949 when he was transferred to the newly formed “weapons system evaluation group” under the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

“I enjoyed the Pentagon, but it was a complicated place to work. We were evaluating the capabilities of the services to perform their missions. … My wife loved it because she got to see a lot and participate in a lot of functions in Washington.”

He’d return to the Pentagon two more times, in 1963 as the director of production and programming for the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff of systems and logistics, and for his last assignment in 1969 as the service’s deputy chief of staff for systems and logistics.

“It’s hard to get anything done. You have to go through so many channels to get approvals or money, through different people. It’s a big bureaucracy,” Goldsworthy said. “I bet you I could go to my old office in the Pentagon, reach into a drawer [and pull out a file] and see they have the same problems that I was working on.”

His tours at the Pentagon bookended his SATAF role at Malmstrom and his position as deputy chief of staff of operations for the Air Proving Ground Command at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, to test new aircraft.

“It was the 100-series airplanes that came out,” he said, referring to the Air Force’s “Century Series” aircraft initiative, which debuted in the 1950s and produced fighter-bomber or interceptor variants such as the F-100 Super Sabre, F-102 Delta Dagger and F-105 Thunderchief.

Goldsworthy was part of a team that conducted suitability tests between 1953 and 1956, signing off that the aircraft could perform their roles.

“It’s hard to pick out an airplane that was more exciting than others. I enjoyed the B-47 [Stratojet],” he said. “It was a six-engine bomber; it was just a nice airplane to fly. We got the seventh [B-52 Stratofortress] bomber off the production line, and we tested that too.”

Goldsworthy said his favorite assignment was at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. In 1967, he became the commander of the Aeronautical Systems Division, which was in charge of detailing specifications and awarding program contracts to get aircraft, missiles and other equipment produced.

He said he felt there was an initiative to “get stuff done” there. Goldsworthy even drew up the specifications for the F-15 Eagle fighter jet.

“It makes me feel old to see those airplanes that I worked so hard being put down in Arizona,” he said, referring to the aircraft boneyard. “But I look at some of these new airplanes like the [F-16 Fighting Falcon] and the [F-35 Joint Strike Fighter] and they’re so complicated, I’m not sure I’d be able to fly them.”

The Big 107

Over his career, Goldsworthy flew in more than 30 different types of aircraft, either as the pilot or in the backseat for testing purposes. He received the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal, the Legion of Merit and the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters. “I just worked hard,” he said.

Goldsworthy had a consulting job for Boeing Co. in Seattle after retiring from the Air Force in 1973. Later, he and his wife, Edith, moved into Air Force Village West in Riverside, California, for the community aspect, he said. His wife died in 2010, but Goldsworthy still calls the retirement center, renamed the Westmont village, his home.

He spends his days mostly reading “nonsense fiction,” he said. He’s spent the last year “living a lot like a hermit” due to the COVID-19 pandemic. His two sons were finally able to visit him last month for the first time since it began, he said. He talks to his great-nephews — one an F-35 pilot, the other a chaplain in the Army — from time to time.

“All my Air Force buddies are long gone. That’s one of the penalties to living to be 107,” Goldsworthy said.

According to Patch.com, Riverside Mayor Patricia Lock-Dawson will present Goldsworthy with an award Saturday. The Patriot Guard Riders, a veteran motorcyclist group, will attend for a flag ceremony, along with a few personnel from March Air Reserve Base who will present Goldsworthy with a certificate of achievement for his service. He said he feels humble knowing he may be one of the oldest living Air Force officers still around. “I didn’t aspire to be the oldest,” he added.

“As my one son said, ‘You’ve been through 106 [birthdays], so you shouldn’t be too excited about another one.'”

-By Oriana Pawlyk

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Military.com

Related to: Military History

Video: The Air Force is considering the B-21 for air-to-air combat

Video: The Navy’s F/A-XX may become the first 6th generation aircraft in the world

SiAW: Air Force receives a wildly capable new air-to-ground missile for testing

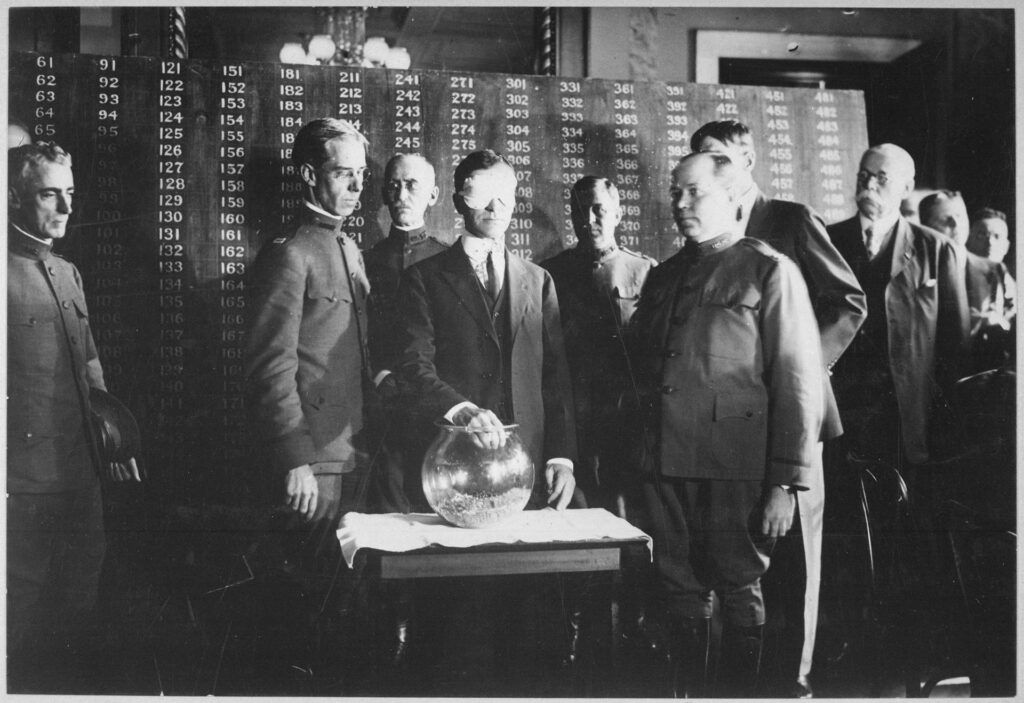

Military draft registration is going down, so Congress wants to take action

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page