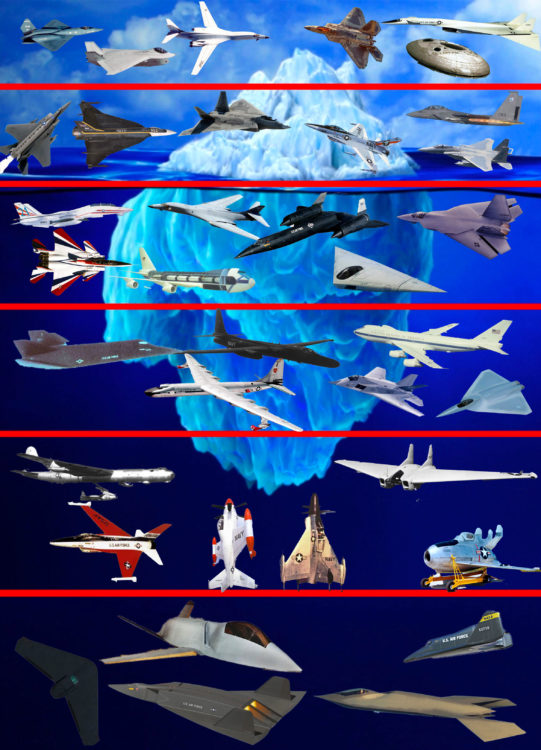

The military aircraft America ‘almost’ bought iceberg

- By Alex Hollings

Share This Article

The United States was the first country on the planet to purchase an aircraft for military applications with the 1909 Wright Military Flyer. Ever since, America has consistently invested heavily in innovating its approach to airpower. From the world’s first plane-mounted gun to the world’s first stealth bomber, Uncle Sam has always been willing to invest in the competitive advantage cutting-edge aviation technology can deliver.

But the first victory a game-changing jet, like the F-22 Raptor or B-2 Spirit, has to secure isn’t in combat: rather, it’s in the secretive confines of experimentation and industry competition, as these jets fly for their lives against the most advanced and capable opponents American industry has to offer. Once a victor is chosen, the losers often fall away into obscurity — with the lucky ones finding a home in aviation museums and the less fortunate occupying space in the dustiest corners of old hangars or worse, wasting away in the sun of America’s aviation boneyards.

And then there are other exotic aircraft designs that deliver incredible new capabilities that don’t fill a pressing need at the moment or that simply cost too much to be practical. These unusual and forward-leaning jets often find a similar fate, destined to do little more than collect dust and serve as a reminder of what could have been.

In this iceberg, we’ll cover 40 of these secretive prototypes and concepts that came close to making it into production, but fell short of securing a contract.

What is an iceberg chart?

Iceberg charts blew up in popularity in 2020 and 2021 thanks to a rash of Reddit posts and YouTube videos leveraging the model for everything from cryptids to economic systems. The premise is based on a longstanding academic metaphor that likens the understanding of a topic to an iceberg: with the most commonly understood bits of information making up the visible part of the iceberg above the surface of the water, and the larger breadth of lesser-known facts making up the body of the iceberg beneath the surface.

In common use in places like Reddit and YouTube, the deeper below the surface you go (into the darker, murkier depths), the more uncommon, secretive, or unusual the information. Often icebergs are split into several levels for the sake of organization.

If you find you really like this model of presenting information, there’s an entire subreddit devoted to iceberg charts that you can visit here.

Aircraft Iceberg Level 6: Flying High

YF-23

The YF-23 was Northrop Grumman’s entry into the Advanced Tactical Fighter competition. It ultimately lost out to Lockheed Martin’s YF-22, which would go on to become the F-22 Raptor. Two YF-23 prototypes were built. The first, dubbed the Black Widow II by those involved with the program, was all black and powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney engines that allowed the jet to supercruise at Mach 1.43 during its first round of testing in 1990. The second YF-23, painted grey and dubbed Grey Ghost, switched to General Electric YF120 engines, which offered improved supercruise capabilities, reaching Mach 1.6 in testing, just slipping past the YF-22’s Mach 1.58.

Ultimately, while the YF-23 could just about match the F-22’s aerobatics, Lockheed won the perception war by demonstrating their fighter’s capabilities in a more dynamic way. Lockheed test pilots showed off the aircraft’s ability to utilize a high angle of attack, fired missiles, and executed maneuvers that placed more than 9Gs worth of force on the airframe. While the YF-23 could have done the same, Northrop didn’t in the demonstration. Many contend that it was this salesmanship, rather than strictly platform capabilities, that helped the YF-22 stand out in the minds of defense officials.

XB-70

In the late 1950s, the North American XB-70 Valkyrie looked like it had been ripped straight out of the pages of a science fiction comic book. With a sharp, angular design, six afterburning engines, and the latest targeting, navigation, and electronic warfare systems America could muster, the XB-70 was to become the world’s biggest, fastest, and highest-flying bomber in history… Until it wasn’t.

Today, the Valkyrie serves not just as a reminder, but arguably as the very pinnacle of the Cold War aviation philosophy of circumventing defenses through ever higher and faster platforms. The XB-70, like America’s famed SR-71 Blackbird and its defunct interceptor sister the YF-12, aimed to deliver on both in classic American style: by burning through budgets like jet fuel.

F-22B

Before the first Raptor took flight, the Air Force wasn’t looking for only a single-seat fighter. In fact, the prototype order the Air Force gave Lockheed Martin called for seven single-seat iterations of the aircraft for testing (F-22As) and two twin-seat F-22Bs.

From pilot training to distributing the mental load of elaborate and advanced combat operations, there are a number of reasons for building a fighter with room for a second occupant. Like the F-14 Tomcat, F-15E Strike Eagle, and many other twin-seat fighters, the rear operator can track enemy targets and friendly aircraft, increase situational awareness, operate electronic warfare suites and countermeasures, and generally allow the pilot to focus on flying.

The twin-seat F-22B never made it into production, but if it had, it may have made the air superiority fighter a more promising option as a medium-range bomber or made it better suited for the attack role fighters aboard carriers often have to fill. There’s a whole lot of maybe’s balled up in that second ejection seat that never found its way into the Raptor.

X-32

The X-32 was Boeing’s entry into the Joint Strike Fighter competition that ultimately produced the Lockheed Martin F-35. Boeing’s X-32 design aimed to minimize both production and maintenance costs by leveraging a large one-piece carbon fiber composite delta-wing and as many shared systems between variants as possible.

Its large chin-mounted air intake was the result of Boeing’s decision to use a direct-lift thrust-vectoring system to support short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) operations. This allowed the X-32 to conduct STOVL operations using just one engine. (By comparison, the F-35B uses both the primary engine and a lift fan in its body.)

VZ-9

The Avrocar VZ-9 was quite literally intended to be a real-life flying saucer. First designed for the Canadian military and then purchased by the United States for further testing, the VZ-9 was intended to answer looming concerns about airstrips being wiped out in the early days of a large-scale conflict. Rather than needing runways to take off and land, the VZ-9 would do so vertically.

In order to achieve this vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) capability, Avrocar’s John “Jack” Frost aimed to use the exhaust from the turbojet engines to drive a circular turborotor to produce a cushion of thrust beneath the circular aircraft. This would allow the Avrocar to hover at low altitudes. The thrust from the engines could then be directed backward, pushing the aircraft forward and, according to their design, allowing it to operate like a highly capable fighter. Ultimately, the VZ-9 just never quite lived up to its lofty expectations.

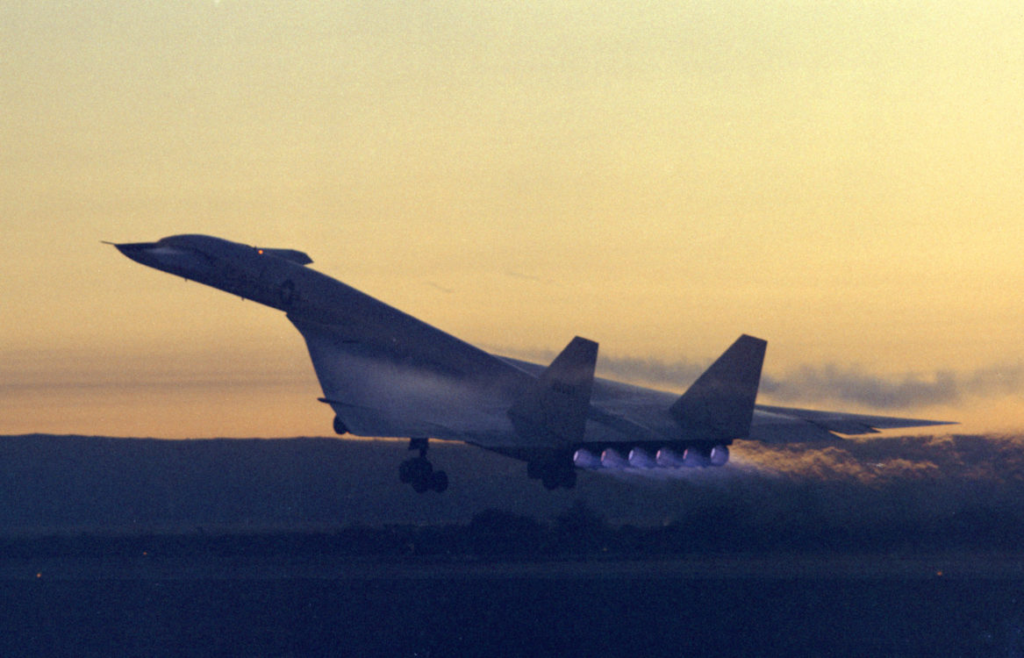

B-1A

Today’s B-1B Lancer is America’s only supersonic heavy-payload bomber, with variable sweep-wing geometry, reminiscent of Cold War fighters like the F-14 Tomcat, and with a top speed of Mach 1.2. However, its direct predecessor offered even more power, with an intended top speed in excess of Mach 2.

The B-1A was ultimately canceled by the Carter administration, citing increasingly capable stand-off missiles and ICBMs as a more cost-effective nuclear deterrent. The program was brought back during the Reagan administration, but by then, priorities had shifted, resulting in a lower top speed but higher maximum payload.

Aircraft Iceberg Level 5: At the surface

F-15GSE

In 2006, a team from Boeing proposed an incredible new use for America’s legendary F-15 Eagle that called for mounting a 45-foot rocket to its back. This rocket-carrying fighter would be given the seemingly logical (while still entirely dramatic) moniker of F-15 Global Strike Eagle, and it could have revolutionized how America deployed hypersonic weapons or put small payloads into orbit.

The idea was to use the Eagle’s powerful afterburning turbofan engines and the incredible amount of lift offered by its design to ferry rockets up to high speeds and altitudes before releasing them to ignite and fly the remainder of the journey into orbit. Launching orbital payloads from an aircraft would eliminate the need for expensive rocket-launch facilities while making it possible for F-15s to rapidly deploy small payloads into orbit from anywhere on the planet with an airstrip and a hangar.

F-15SE

Back in 2009, Boeing’s Silent Eagle aimed to make the world’s most prolific air superiority fighter into something more by injecting stealth into the F-15’s legendary DNA. The result may have been the most broadly capable F-15 the world had ever seen, delivered just in time to compete with what would become a foreign sales powerhouse, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

The F-15SE Silent Eagle aimed to bridge the gap between fourth- and fifth-generation fighters, incorporating elements of the stealth and situational awareness offered by the world’s most advanced tactical jets into an already legendary fighter airframe. With 58,000 pounds of thrust on tap, internal weapons carriage capabilities, a reduced radar signature, advanced avionics, and the Strike Eagle’s multi-role pedigree, this fighter may have been the most capable 4th generation platform on the planet by the time it would have rolled onto the flight lines of prospective buyers hailing from Canada to Japan and everywhere in between.

F-15N

The F-14 Tomcat may be a legendary fighter that got the Hollywood treatment in 1986’s Top Gun, but for a short time in the 1970s, the Navy considered tossing the Tomcat in favor of flying the F-15 from its aircraft carriers instead.

The F-15 wasn’t originally designed to serve aboard aircraft carriers, but it was designed to dominate the skies during the Cold War. With the Navy set to begin purchases of Grumman’s pricey F-14, McDonnell Douglas entered a proposal for the F-15N Sea Eagle and it wasn’t a bad shot.

The F-15A already had a tailhook, intended for use on short airstrips or in an emergency, but a carrier fighter needs to rely on its hook for every landing, so a larger reinforced hook was added to the design. To make for easier storage below deck on carriers, the wings would fold up at a 90-degree angle a bit more than 15 feet from each tip. The landing gear would also have to be swapped out for a more rugged set that could withstand the abuse of carrier landings on a rocking ship. McDonnell Douglas said they’d design the new gear if the Navy wanted to move forward with the aircraft.

With these changes incorporated, the F-15 only gained a paltry 3,000 pounds, which, combined with better maneuverability, a higher top speed, and a much lower price, all made this new Sea Eagle sound like a pretty good deal… but there was one glaring shortcoming. Capable as the F-15N may have been, it couldn’t carry America’s latest and greatest air-to-air missile, the AIM-54 Pheonix.

F-16XL

For more than 40 years, the F-16 Fighting Falcon has served as the backbone of the U.S. Air Force’s fighter fleet, but one year before the first F-16 entered service, the team behind its development had already developed a better F-16 in the F-16XL. The fighter was so capable, in fact, that it went from being nothing more than a technology demonstrator to serving as legitimate competition for the venerable F-15E in the Air Force’s Advanced Tactical Fighter program. Ultimately, it would lose out to the F-15E based on production cost and redundancy of systems, but many still contend that the F-16XL was actually the better platform.

Its new wing design, which saw a 50-degree angle near the root of the wing for supersonic performance and a 70-degree angle where the wings extended for subsonic handling, offered more than double the surface area of the F-16’s wings.

Those massive wings gave the F-16XL a nearly doubled fuel capacity, and the additional lift coupled with 633 square feet of underwing space allowed for the addition of an astonishing 27 hardpoints for ordnance. Remarkably, the F-16XL seemed to outperform its smaller predecessor in nearly every way, prompting the Air Force to take an interest in the idea of actually building this new iteration fighter that wasn’t originally meant for production.

FB-22

Lockheed Martin’s F-22 Raptor remains the most potent air superiority fighter in the skies today, and its immense success prompted some within America’s defense apparatus to call for a bigger version of the stealth jet to serve as a highly survivable medium-range fighter/bomber. The effort, dubbed the FB-22, reportedly gained the favor of Air Force Secretary James Roche among others, before ultimately being discarded for other bomber options. In fact, discussion about the FB-22 may have helped get the B-21 Raider off the drawing board and into active development.

The FB-22 stealth bomber would have shared a number of components with its fighter counterpart, though it would have added a delta-wing similar to the F-16XL’s that offered a big increase in range and payload, as well as a second crew member – though at the cost of some of the legendary platform’s acrobatic performance. The goal was to meet the Air Force’s need for a regional or medium-range bomber that could bridge the capability gap between fighter air-to-ground operations and long-range bombers with heavy payload capabilities.

If it had been put into production, the FB-22 could have been the stealthiest fighter/bomber on the planet, and the only supersonic stealth bomber ever to enter operational service for any nation to date. But it might be more appropriate to think of it as a potential stealthy replacement for the F-15E Strike Eagle.

VOUGHT 1600

The Vought 1600 was an effort to put the Air Force’s broadly capable F-16 Fighting Falcon on America’s aircraft carriers.

In order to meet the needs of the Navy, the Vought 1600 was larger than the F-16A, stretching some three feet further, with a 33-foot three-inch wingspan that was a full two feet broader than the Air Force’s version of the fighter. The breadth of the wings grew, covering a total area of 269 feet and giving the aircraft better stability at lower speeds. The fuselage was flattened a bit and made broader, and its canopy was designed to pivot forward. This configuration was different from the F-16’s, but can now be found on the F-35.

To withstand carrier landings, heavier-duty landing gear had to be affixed to the Vought 1600’s belly, alongside the standard carrier equipment like a landing hook. The fuselage itself was made stronger, and to offer the engagement range the Navy needed, a pulse-doppler radar for beyond-visual range targeting was also added.

All told, the structural changes needed to make the F-16 into the Vought 1600 added more than 3,000 pounds to the small aircraft. Further changes were made to the fuselage and wings as subsequent iterations of the Vought 1600 came to fruition. The V-1602, for instance, had even more wing area at 399 square feet and was given a heavier GE F101 engine.

Aircraft Iceberg Lever 4: Just beneath the surface

NATF-22

As the F-22 program matured, it impressed a lot of people – including members of Congress, who pressed the Navy to consider adopting a sweep-wing version of the new fighter under the NATF (Naval Advanced Tactical Fighter) program that began in 1988.

In order to make the F-22 suitable for carrier duty, Lockheed Martin would have had to incorporate a number of significant changes to the F-22’s design. Alongside the usual changes one can expect out of a carrier-capable aircraft (things like a strengthened fuselage and added tail hook), a Navy variant of the F-22 would have incorporated a variable sweep-wing design similar to that employed by the Navy’s existing F-14 Tomcats.

This addition, perhaps more than any of the others, would have been a real challenge for engineers to contend with. Sweep wings were expensive to maintain, to begin with, but incorporating a sweep-wing design into a stealth aircraft may have been nearly impossible without sacrificing some degree of low observability.

A-12 AVENGER II

On 13 January 1988, a joint team from McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics was awarded a development contract for what was to become the A-12 Avenger II, not to be confused with Lockheed’s proposed A-12 of the 1960s, which sought to arm an SR-71 sibling jet with air-to-air weapon systems. Once completed, the Navy’s A-12 would have been a flying wing design reminiscent of Northrop Grumman’s B-2 Spirit or forthcoming B-21 Raider, though much smaller.

Although the A-12 Avenger II utilized a flying wing design, its overall shape differed from the triangular B-2 Spirit under development then for the Air Force. The sharp triangular shape of the A-12 eventually earned it the nickname, the flying Dorito.

For some time, it seemed as though the A-12 Avenger II program was going off without a hitch, but then, seemingly without warning, it was canceled by Defense Secretary (and future Vice President of the United States) Dick Cheney in January of 1991. It was later revealed that the A-12 Avenger II was significantly overweight, over budget, and behind schedule.

YF-12

The SR-71 Blackbird may be among the most iconic airframes of the Cold War, but this incredibly fast design wasn’t always intended to serve only as a high-flying set of eyes. In fact, a variant of the SR-71’s predecessor program, the faster and higher-flying A-12, actually had a fighter-interceptor sibling in the form of the YF-12, and eventually (in theory at least) the F-12B.

The biggest changes the YF-12 saw when compared to its A-12 sibling were at the front of the aircraft, where a second cockpit was added for a fire control officer tasked with managing the interceptor’s air-to-air arsenal.

The nose was also modified to accommodate the Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire-control radar that had been developed for use in the defunct XF-108 program.

But the most important change between the A-12 and the YF-12 came in the four bays designed originally to house powerful cameras, film, and other reconnaissance equipment. One of the four bays was converted to house fire control equipment, while the others were modified to house an internal payload of three Hughes AIM-47 Falcon air-to-air missiles.

ASF-14

While the F-14D took on the title “Super Tomcat,” the effort to modernize the F-14 began under the moniker “ST21,” which, appropriately enough, stood for “Super Tomcat for the 21st Century,” and make no mistake, that’s exactly what it could have been, with improved avionics, more power, more range, and more capability across the board.

But while both the ST21 and AST21 were billed as re-manufacture programs for existing Tomcats along with new-build aircraft, Grumman’s pitch to the Navy eventually included an entirely new-build Tomcat dubbed the ASF-14.

The ASF-14 would have looked like its F-14 predecessors, but the similarities would have been largely skin-deep.

The ASF-14, with some 60,000 pounds of thrust, better thrust-to-weight ratio than the F-14D, thrust vector control, massive internal fuel stores, huge payload capabilities, and incredible situational awareness provided by powerful onboard radar, and a multitude of sensor pods, could have been a 4th generation fighter with few – or maybe no – peers to this very day.

F-15 ACTIVE

In 1984, the Flight Dynamics Laboratory out of the Air Force Aeronautical Systems Division awarded a contract to McDonnell Douglas to begin development on an F-15 concept that would allow these highly capable fighters to take off and land on short or damaged runways, dubbed the F-15 STOL/MTD In order to accomplish that goal, they incorporated front canards (actually the real tail sections from an F/A-18 Hornet) and thrust-vector control.

In 1993, the Air Force handed the keys to their F-15 STOL/MTD to NASA for the purposes of their new ACTIVE program, which was short for Advanced Control Technology for Integrated Vehicles. Building off of their previous digital flight control programs like HIDEC and Performance Seeking Control (PSC), NASA opted to retain the unusual wing layout of their new F-15 in the ACTIVE program, hoping to use the fighter as a testbed for a whole swath of systems that could come to find use in the next generation of fighters.

The F-15 Active ultimately proved to be significantly more capable than even the F-15 Eagle, but was never actually considered for production.

747 CMCA

During the Cold War, Boeing developed plans to load a 747 with as many as 72 air-launched cruise missiles to serve as a long-range arsenal ship capable of wiping out targets from hundreds of miles away. The design, dubbed the 747 Cruise Missile Carrier Aircraft (CMCA), could have been an extremely cost-effective alternative to America’s current fleet of heavy-payload bombers in a wide variety of mission sets.

Ultimately, the 747 CMCA never made it off the drawing board, with the Reagan administration pulling the B-1 program out of mothballs and the B-2 entering service shortly thereafter – but it may be time the United States revisited the idea of leveraging these or similarly capable commercial airframes for more than just ferrying cargo and passengers.

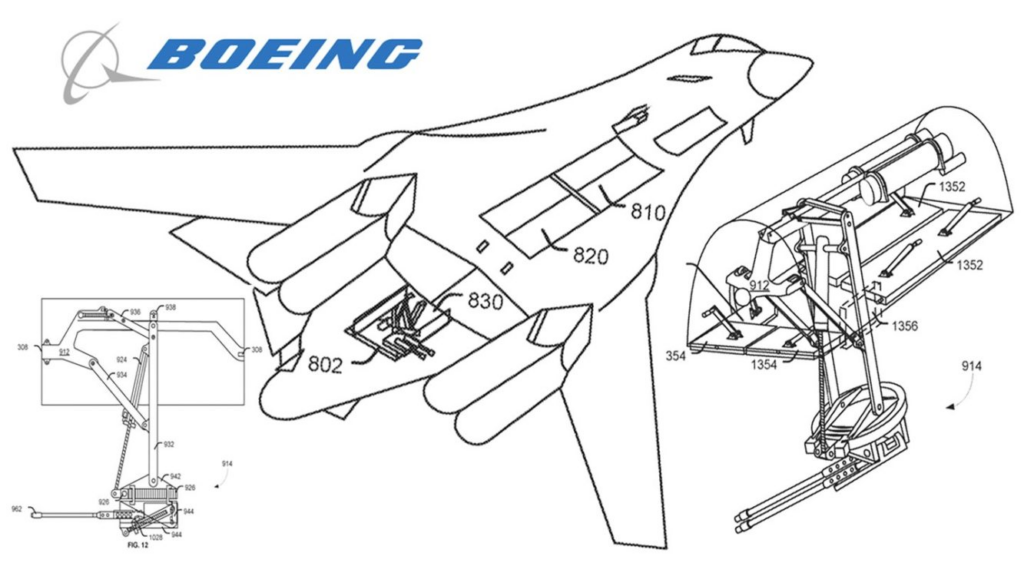

B-1B Gunship

In 2018, Boeing filed patents for a number of potential cannon mounting solutions for the supersonic heavy payload bomber, the B-1B Lancer, with the intent of creating a B-1B gunship similar in capability to the famed Spooky AC-130 and its most recent successor, the AC-130J Ghostrider.

Boeing’s patents indicate a number of cannon-mounting methods and even types and sizes of weapons, giving this concept a broad utilitarian appeal. America currently relies on C-130-based gunships that, while able to deliver a massive amount of firepower to a target, max out at less than half the speed that would be achievable in a B-1B gunship. The Lancer’s heavy payload capabilities and large fuel stores would also allow it to both cover a great deal of ground in a hurry, but also loiter over a battlespace, delivering precision munitions and cannon fire managed by a modular weapon control system.

While the patents indicate Boeing’s interest in prolonging the life of the venerable Lancer, there’s been little progress toward pursuing this unusual design.

Aircraft Iceberg Level 3: The water’s getting murky

315B U-2

When U-2 designer Kelly Johnson first approached the U.S. Air Force with his CL-282 design that would culminate in the U-2, he was dismissed outright by the legendary commander of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) and engineer behind America’s strategic bombing campaigns in the Pacific theater of World War II, Curtis LeMay. True to his reputation, LeMay reportedly told Lockheed’s team that he had no interest in an airplane “without wheels or guns.”

Lockheed seemed to take that criticism to heart, and while they didn’t change out the landing gear or add any guns to the U-2, they did take a crack at adding missiles.

Dubbed the 315B design, this new iteration of the U-2 would come with a second crew station, not unlike the two-seat U-2 training aircraft Lockheed already had in production. That second crew member would serve as a sort of Radar Intercept Officer, similar to the backseater in operational Navy fighters of the day like the F-14 Tomcat.

Having a second seat in the aircraft effectively splits the cognitive load required to operate it. In other words, the pilot can focus specifically on flying the aircraft while the person in the back seat manages communications systems, tracks friendly and enemy positions, helps navigate, and importantly in the case of the 315B U-2, operates the on-board weapons systems and defensive countermeasures.

F-117N

In 1993, four years after the U.S. Air Force unveiled the Nighthawk to the world, Lockheed approached the U.S. Navy with a proposal for a carrier-based iteration of the famed “stealth fighter.” This new F-117N would be a low-observable (stealth) all-weather strike aircraft. At the time, it seemed like a logical progression for America’s air power.

Seemingly aware that the operational F-117 wasn’t the most capable combat aircraft, Lockheed’s new pitch offered a drastically improved iteration of the platform, complete with double the internal payload capacity of the first. The wings would be given a 42-degree sweep, rather than the Nighthawk’s 50-degree, and would extend out 50% further, to 64 feet. At the tail of the aircraft, additional horizontal ailerons were added to make it more manageable at the low speeds required for carrier landings.

Not satisfied with the Nighthawk’s top speed of right around 680 miles per hour, Lockheed looked to the more powerful F114 engines that would later find a home in the Super Hornet. These afterburning turbofans built by GE produced 13,000 pounds of thrust under normal operation and as much as 22,000 pounds with the afterburner engaged. Using a pair of these engines in the Seahawk would have made it significantly faster than its Air Force sister, and potentially could have pushed all the way into supersonic flight.

NB-36

The NB-36 Crusader was an experimental nuclear-powered bomber that actually flew with a nuclear reactor onboard.

The bomber carried a 1-megawatt, air-cooled nuclear reactor that hung on a hook inside its cavernous weapons bay that had to be lowered through the bomb bay doors into shielded underground facilities for storage between flights. Believe it or not – it only gets crazier from there.

In theory, a nuclear-powered bomber could literally stay airborne for weeks at a time (if not longer) and could reach any target on the planet without the need to land or refuel.

The reactor would power four GE J47 nuclear-converted piston engines generating 3,800 hp, which were then augmented by four additional 23.13 kn turbojet engines that produced 5,200 lbs of thrust. The HTRE-3 was a direct-cycle system that pulled air into the compressor of the turbojet and through a plenum and intake that led to the core of the reactor where the air served as coolant. From there, the super-heated air would travel into another plenum that led to the turbine section of the engine before exiting as exhaust out the back.

EP-X (U-2)

After multiple successful efforts to fly the U-2 Spy Plane from its aircraft carriers, the U.S. Navy set out to develop a version of the platform uniquely suited for carrier duty in 1974.

A new nose section was added to house an X-band phased array AN/APS-116 radar. Equipment pods on the leading edges of each wing were also added. On the left side, the pod housed a Return Beam Vidicon camera that could produce high-fidelity images without the need for film. The pod on the opposite wing housed an AN/ALQ-110 radar signal tracker that was linked to another camera.

Inside the aircraft’s payload bay, a suite of electronics were added, including an actual data link that would allow the U-2 to send radar data back to the aircraft carrier, ground-based installations, or any other ships with line-of-sight in almost real-time. A Navy-variant U-2 carrying these systems represented a significant leap forward in maritime surveillance for America’s carriers, but by then, aircraft weren’t the only way to keep tabs on large swaths of ocean.

The Navy dubbed this heavily modified U-2R the EP-X, but even the added capability of this new platform wasn’t enough to outpace rapidly advancing satellite technology. For the third time in a decade, the U-2 had proven it could operate aboard America’s aircraft carriers, but was deemed too impractical for continued use.

747 AAC

The 747 has proven itself to be an extremely capable aircraft for a wide variety of applications, so it seemed logical when, in the 1970s, the U.S. Air Force began experimenting with the idea of converting one of these large aircraft into a flying aircraft carrier full of “parasite” fighters that could be deployed, and even recovered, in mid-air.

Initial plans called for using the massive cargo aircraft Lockeed C-5 Galaxy, but as Boeing pointed out at the time, the 747 actually offered superior range and endurance when flying with a full payload. According to Boeing’s proposal, the 747 could be properly equipped to carry as much as 883,000 pounds.

Boeing’s 60-page proposal discusses the ways such a program could be executed, but lagging questions remained regarding the fuel range of a 747 carrying such a heavy payload and about how the fighters would fare in a combat environment. Previous flying aircraft carrier concepts showed that the immense turbulence from large aircraft (and their jet engines) made it extremely difficult to manage the fighters they would drop, especially as they attempted to return to the aircraft after a mission.

X-44 MANTA

Way back in 1999, Lockheed Martin had a plan to field a delta-shaped stealth fighter that skipped the need for a conventional tail section, in the F-22-based X-44 Manta.

Instead of using a conventional tail section with both vertical and horizontal control surfaces, the Manta aimed to leverage thrust-vector control, or directing the flow of the engine’s thrust to give the aircraft the aerobatic capabilities it would need in a high-end dogfight.

The X-44′s name, or more appropriately, its acronym, gets straight to the intent behind the concept. After decades of rapid fighter development, some things had simply come to be considered standard fare for a capable tactical aircraft: things like a conventional tail section with vertical and horizontal control surfaces. While both the F-22 and later, the F-35, adopted slightly different tails than you’d find on a non-stealth 4th-generation fighter like the F-16, the X-44 Manta aimed to pull off the same sort of maneuverability without the need for all those tail surfaces. With no tail section, the aircraft’s radar return would be dramatically reduced, creating an even stealthier fighter than America’s highly capable F-22.

Today, elements of its design seem to be present in artist depictions of America’s next stealth fighter, being developed in the NGAD program.

X-24C

The X-24C was part of an effort to field hypersonic research aircraft beginning in the late 1960s. Taking on the role of lead contractor, Lockheed worked side by side with the Air Force’s National Hypersonic Flight Research Facility and NASA to develop and field two hypersonic test aircraft, with each vehicle slated for 100 flights.

The decision was made to equip this new L-301 program’s aircraft, unofficially dubbed the X-24C, with a new LR-105 rocket engine found at the time in the Atlas series of rockets. The LR-105 would launch and accelerate the X-24C to hypersonic speeds, not unlike the rocket engine in the X-15. From there, a second hydrogen-fueled, air-breathing ram/scramjet (supersonic-combustion ramjet) engine mounted on its belly would take over.

The scramjet engine would propel the X-24C at sustained speeds in excess of Mach 6, reaching intended peak speeds that were higher than Mach 8, or more than 6,130 miles per hour. The aircraft itself resembled the lifting body design leveraged by the Martin Marietta X-24A and B programs that tested unpowered reentry flight characteristics.

Level 2: Deep waters

F-16SFW

In the early 1980s, the team behind America’s legendary F-16 Fighting Falcon had plans to literally reverse its wing design by adding forward-swept wings to the multi-faceted fighter. The goal wasn’t to put an exotic new design into service initially, but rather to create a platform DARPA (or the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) could use to assess just how viable this unstable approach to wing design could be in modern supersonic fighters.

The effort would ultimately result in the unusual-looking Grumman X-29 winning DARPA’s contract and securing funds for two fully functional prototypes, but not before General Dynamics could take a crack at making their broadly capable F-16 fit the bill first.

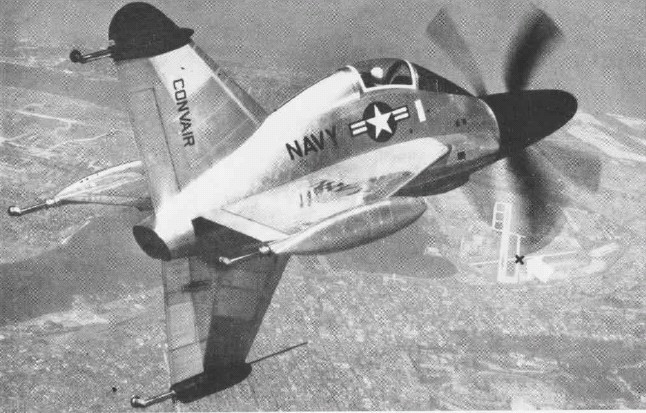

Lockheed XFV

In June of 1951, Lockheed was awarded a Navy contract to build the XFV-1; a prototype fighter with traditional wings, a massive reinforced X-shaped tail, and a 5,850 horsepower turboprop engine spinning a pair of three-bladed contra-rotating propellers that made the aircraft look like the bastard child of a helicopter and a prop-driven fighter. Most unusual of all, the aircraft was designed to take off and land on its tail, with its nose pointed straight up in the air.

Unfortunately, the Allison YT40-A-6 turboprop engine installed on the prototype was not powerful enough to manage actual vertical take-offs or landings. Instead, Lockheed planned to use the forthcoming (and more powerful) Allison T54 engine, which would produce 7,100 horsepower, but issues with the engine’s development meant the XFV’s desperately needed power plant would never arrive.

GRB-36F

The Convair B-36 Peacemaker was, in truth, a crazy airplane in itself. With a 230-foot wingspan, it dwarfed even the massive B-52 Stratofortress while in service. The aircraft was designed to carry nuclear payloads from the United States to Germany and back without needing to land, but its heavy payload capabilities and long range made it a natural choice for the Air Force’s FICON (Fighter Conveyor) program – which is military speak for a flying aircraft carrier.

The premise saw the B-36 carrying fighters internally to extend their operational range and then deploying them via a lowering boom, where they could serve as protection for the bomber, reconnaissance assets, or even execute offensive operations of their own before returning to the B-36 for recovery.

The U.S. Air Force ultimately did away with the concept thanks to the advent of mid-air refueling, which dramatically increased the operational range of all varieties of aircraft and made a flying aircraft carrier concept a less cost-effective solution.

Convair XFY

Convair’s take on the vertical take-off and landing premise shared a number of similarities with Lockheed’s. Like the XFV, Convair’s XFY Pogo was designed to sit upright on its tail so it could leverage its pair of three-bladed contra-rotating propellers to take off like a helicopter. Then, once in the air, the aircraft would re-orient itself to fly forward like a traditionally prop-driven plane.

Pilots had to look over their shoulder and back to the ground as they slowly lowered the fighter down onto its tail. Eventually, a low-power radar system was installed that would help the pilot gauge their altitude with a series of lights, but landing was still tricky. It quickly became apparent that the Navy’s plan to put these fighters on a wide variety of non-carrier vessels just wouldn’t work, because only the best pilots in the force had a chance at landing the plane.

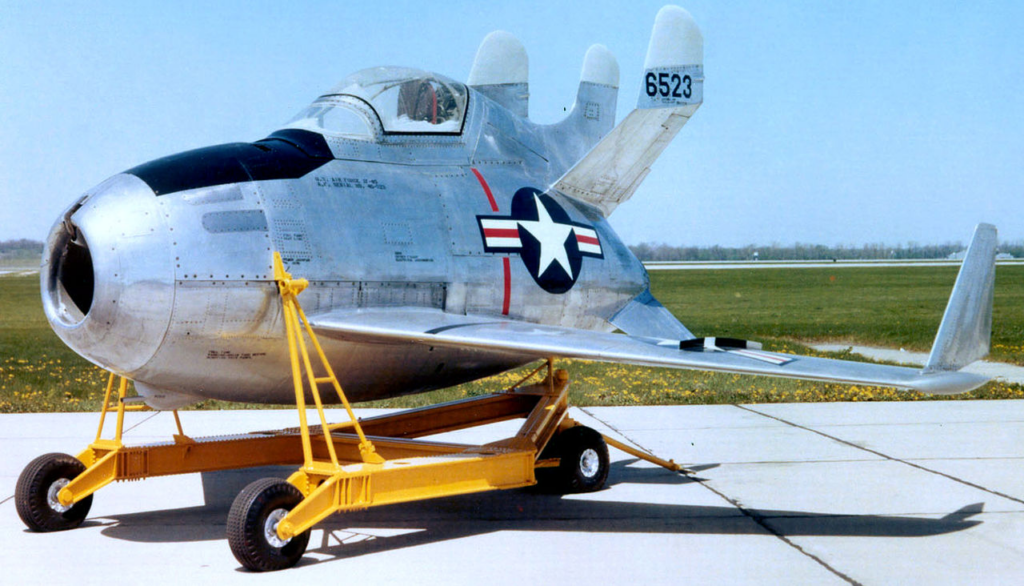

XF-85

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation’s XF-85 Goblin was to be a fighter unlike any other. It was tiny, so small it was often referred to as a “parasite fighter,” and instead of taking off from runways, it was intended to be deployed from the inside of flying aircraft carriers.

The single-seat fighter was 14 feet 10 inches long with a 21-foot wingspan that could fold up to fit into a B-36’s bomb bay. The aircraft weighed in at under 4,000 pounds and was powered by a single Westinghouse XJ34-WE-22 turbojet engine that produced a respectable 3,000 pounds of thrust. The turbojet would push the XF-85 Goblin to a top speed of 650 miles per hour, with an operational ceiling of 48,000 feet. To hold its own in a fight, the parasite fighter was armed with four .50 caliber MR Browning machine guns. Despite its small size and lightweight construction, the Goblin still had a fully functional ejection seat in case the aircraft was hit by enemy fire.

YRF-84F

The YRF-84F Ficon was another “parasite” fighter intended to be carried aloft by a B-36-bomber-based flying aircraft carrier.

The idea was similar to that of the later proposal from Boeing for the 747 AAC, carrying the fighters internally to extend their operational range and then deploying them via a lowering boom, where they could serve as protection for the bomber, reconnaissance assets, or even execute offensive operations of their own before returning to the B-36 for recovery.

The U.S. Air Force ultimately did away with the concept thanks to the advent of mid-air refueling, which dramatically increased the operational range of all varieties of aircraft and made a flying aircraft carrier concept a less cost-effective solution.

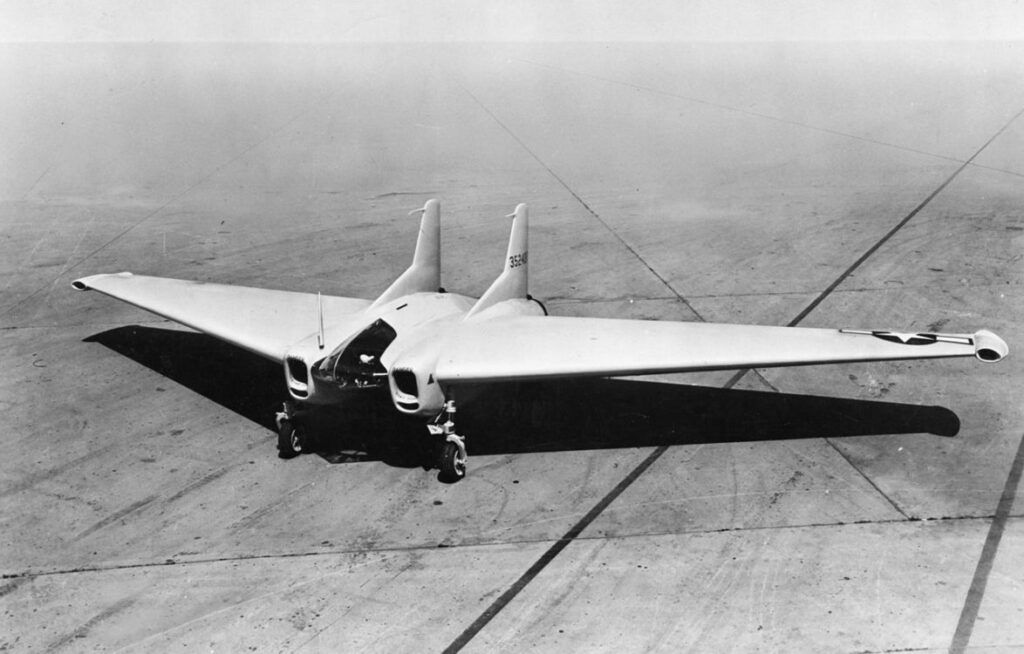

XP-79

The XP-79 was a unique flying-wing fighter developed to literally crash into encroaching enemy bombers, earning it the nicknames “flying ram” and “flying chainsaw.”

It was a design conceived by John K. (Jack) Northrop himself, and was one of a number of platforms developed by Northrop to leverage the flying wing design. Today, Northrop Grumman continues to advance flying wing designs, most notably in the form of the in-service B-2 Spirit and forthcoming B-21 Raider.

The XP-79 was much smaller than its stealthy successors would be, with a fuselage built only large enough for a single pilot to lay down in horizontally, marking this aircraft’s first significant departure from common flying wing designs as we know them today. Northrop and his team believed that pilots would be able to withstand greater G forces if they were oriented in the laying position, and because the XP-79 was being designed to utilize jet propulsion, the shift seemed prudent. Northrop, in fact, had already used this cockpit layout in another experimental aircraft just a few years earlier, the MX-334.

The most unusual thing about the aircraft wasn’t its unique propulsion, nor was it the unusual way the pilot rode – it was the way the aircraft was meant to engage enemy aircraft. The name Flying Ram wasn’t just a bit of artistic license. The heavy-duty welded magnesium monocoque construction made the aircraft exceptionally strong – and that was by design. Northrop didn’t intend for the XP-79 to shoot enemy bombers down, he wanted it to fly right through them.

Level 1: The murkiest depths

X-20 Dyna-Soar

Born out of Germany’s World War II efforts to create a bomber that could attack New York and continue on to the Pacific, Boeing’s X-20 Dyna-Soar was to be a single-seat craft boosted into the sky atop American rockets. That’s right, in the 1950s, the Dyna-Soar would have been the world’s first hypersonic bomber.

It would soar in the sky in the blurred line between earth’s atmosphere and the vacuum of space, bouncing along the heavens before releasing its payload over Soviet targets miles below. The X-20 was a 1950s science fiction fever dream born of the nuclear age and the earliest days of the Cold War… And according to some experts, it very likely would have worked.

By 1960, the spaceplanes overall design was largely settled, leveraging a delta-shape and small winglets for control in place of a traditional tail. In order to manage the incredible heat of reentry, the X-20 would use super alloys like the heat-resistant René 41 in its frame, and molybdenum, graphite, and zirconia rods all used for heat shielding on the underside of the craft.

That same year, astronauts were chosen to fly America’s new space bomber. Among them was a thirty-year-old Navy test pilot and aeronautical engineer named Neil Armstrong, who would go on to leave the program in 1962. Ultimately, however, the X-20 program was canceled in favor of other space-fairing enterprises.

Boeing Quiet Bird

The largely-forgotten Model 853-21 Quiet Bird is a prototype stealth aircraft that actually predates the F-117’s Have Blue precursor’s first flight by nearly a decade and a half. The effort began as a study into developing a low-observable aircraft to serve as an observation plane for the U.S. Army.

Throughout 1962 and ’63, Boeing experimented with stealth aircraft design concepts for the Quiet Bird, incorporating different shapes and construction materials in an effort to reduce the jet’s radar cross section (RCS) long before Denys Overholser at Lockheed’s Skunk Works would develop the means to accurately calculate an RCS without placing the aircraft in front of a radar array.

Although Boeing’s tests did indeed prove promising, the U.S. Army didn’t fully appreciate the value a stealth aircraft could bring to the fight and the program was ultimately shelved. However, Boeing has credited lessons learned in the development of the Quiet Bird for some of the success they would later find with the AGM-86 Air Launched Cruise Missile.

Flying SDV

A declassified Navy program from 2010 shows a concerted effort to field flying submarines, or SEAL Delivery Vehicles (SDVs), for high-risk special operations.

The Navy’s 2010 study largely leveraged DARPA’s outlined requirements, or Concept of Operations, for a submersible aircraft aimed at transporting special operators. The first was obvious: that the flying submarine could be deployed from existing Navy or auxiliary platforms. The vehicle had to be able to land and take off unassisted from the surface of the water, with an in-flight range of 400 miles or more. It needed to be able to transit at least 12 miles once submerged, and loiter for up to 72 hours while hiding from detection. Perhaps most importantly of all, it also had to be able to traverse those same 12 miles beneath the waves and 400 in the sky on the way back, as well. Two designs were ultimately developed.

Both designs leverage multiple watertight compartments, with one keeping the two-person crew separate from a single personnel compartment capable of carrying six special operators, and the other using two smaller personnel compartments that could each hold three. In both designs, the wings would carry fuel in a membrane that would allow any unoccupied space in the wings to be flooded with seawater while submerged. Likewise, the personnel compartments were intended to be free-flooding when the vehicle was underwater.

Two turbofan motors would propel the vehicle while in flight and on the surface of the water, which would be sealed using torpedo-style doors while submerged to protect them from seawater. Submerged propulsion would be managed by a drop-down azimuthing pod with electric motor, capable of maintaining a speed of 6 knots.

Both variants of the flying submarine concept were to operate at depths of around 30 meters (98.4 feet) and be able to take off and land on specially designed inflatable floats.

YF-118G

Throughout the 1990s, a team of engineers from McDonnell Douglas’ Phantom Works developed and tested a unique stealth aircraft shrowded in the secrecy of Area 51, known to most as the Bird of Prey. Unlike most stealth programs, the Bird of Prey, developed under the alias YF-118G, wasn’t aiming for operational service, but elements of the design and production process are still working their way into Uncle Sam’s hangars to this very day.

Perhaps the most lasting contribution this incredible and exotic airframe made to America’s defense apparatus was in its audacity and subsequent success. While most stealth aircraft are known for their high cost, the Bird of Prey went from a pad of paper to the skies over Area 51 for less than the cost of a single F-35 today. The entire program cost just $67 million from start to finish.

Powered by a single Pratt & Whitney JT15D-5C turbofan engine, which produced just 3,190 pounds of thrust, the Bird of Prey wasn’t a fighter, but it did prove that Boeing had the chops to produce a stealth aircraft while advancing technologies tied to rapid prototyping and single-piece composite material construction.

Kingfish

When Lockheed’s U-2 spy plane entered service, Soviet air defenses were already capable of tracking the high-flying platform, and American officials knew it was only a matter of time before tracking turned to targeting. So the CIA tasked both Convair and Lockheed with developing a new reconnaissance platform that could fly at higher altitudes, at significantly faster speeds, and boast a reduced radar cross-section.

And while Lockheed would ultimately meet these requirements in their eventual SR-71, Convair’s Kingfish was its primary competitor.

The Kingfish leveraged a delta-wing design with two J58 Pratt & Whitney J58 engines (the same that would power the SR-71) tucked deep into its fuselage. Ultimately, the Lockheed proposal won out, owing to a number of factors. (Huge thanks to @condorman6 on Twitter for suggesting we include this one!)

Read more from Sandboxx News

Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is a writer, dad, and Marine veteran.

Related to: Pop Culture

No, Australia never lost the ‘Great Emu War’ of 1932

Why media coverage of the F-35 repeatedly misses the mark